- Ductility-Enhanced UHMWPP Composites via Surface-Modified Cellulose: Comparative Effects of Urethane and Ester Functionalization

Ju-Hong Lee, Jae-Ryong Lee, Won-Bin Lim, Jin-Gyu Min, Ji-Won Lee, Ji-Hong Bae*,†

, and PilHo Huh†

, and PilHo Huh†

Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, Pusan National University, Busan 609-735, Korea

*Research Institute of Industrial Technology, Pusan National University, Busan 609-735, Korea- 표면 개질 셀룰로오스를 활용한 연신율 향상 초고분자량 폴리프로필렌 복합체: 우레탄 및 에스터기의 비교 연구

부산대학교 응용화학공학부, *부산대학교 생산기술연구소

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

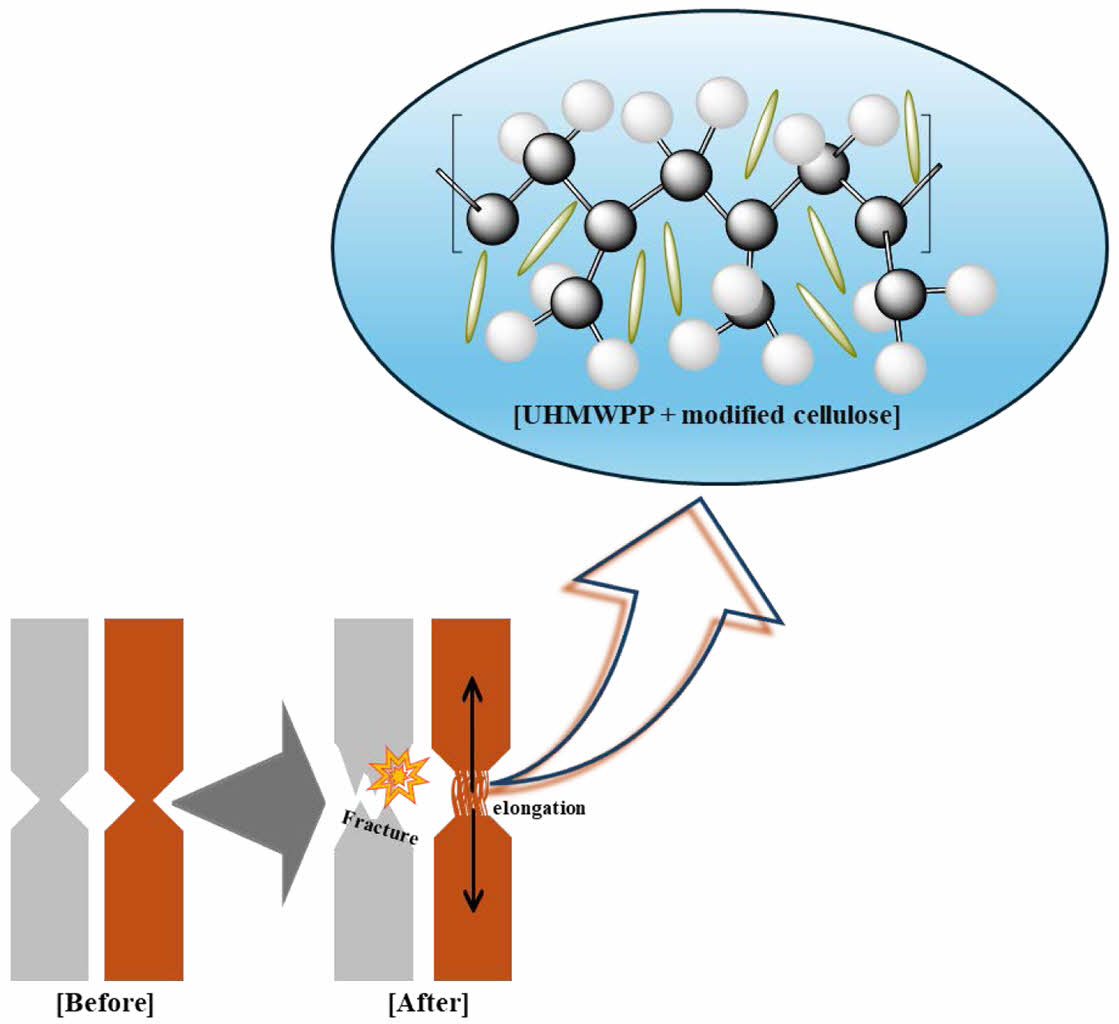

To improve the mechanical properties of ultra-high molecular weight polypropylene (UHMWPP) without compromising its low density, cellulose nanofibers (CNFs) were surface modified with octadecyl isocyanate (ODI) and vinyl ester (VE), followed by compounding with UHMWPP. Since cellulose contains hydrophilic hydroxyl groups, it is inherently incompatible with hydrophobic polymer matrices. To address this, ODI introduced hydrophobic long alkyl chains via urethane bond formation with hydroxyl groups, whereas VE was incorporated through an esterification reaction to replace surface hydroxyl groups and render the surface hydrophobic. These modifications were confirmed using Fourier-transform infrared (FTIR) spectroscopy. The modified CNFs (m-CNFs) were processed into fine powders with uniform particle sizes in the micrometer range via spray drying. The hydrophobic nature of m-CNFs was further verified by contact angle measurements and solvent dispersion tests. Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) revealed the distribution of m-CNFs in the UHMWPP matrix. The composites were fabricated using a twin-screw extruder, and their tensile properties were evaluated using a universal testing machine. The incorporation of m-CNFs significantly enhanced the mechanical performance of the UHMWPP composites, particularly by improving ductility while maintaing tensile strength.

초고분자량 폴리프로필렌(UHMWPP)의 낮은 비중을 유지하면서 기계적 특성을 향상시키기 위해, 셀룰로오스 나노섬유(CNF)를 옥타데실이소시아네이트(ODI)와 비닐에스테르(VE)를 이용해 표면 개질하고 이를 UHMWPP와 복합화하였다. 셀룰로오스는 표면에 친수성 하이드록시기를 가지고 있어 소수성 고분자와 상용성이 낮다. 이를 개선하기 위해 ODI는 하이드록시기와 우레탄 결합을 형성하여 소수성의 긴 알킬 사슬을 도입하였고, VE는 에스터화 반응을 통해 표면 하이드록시기를 치환하여 소수성을 부여하였다. 이러한 표면 개질은 푸리에 변환 적외선 분광법(FTIR)을 통해 확인하였다. 개질된 셀룰로오스(m-CNF)는 분무 건조 공정을 통해 수 마이크로미터 크기의 균일한 분말로 가공되었고, 접촉각 측정 및 용매 분산 실험을 통해 소수성이 향상된 것을 확인하였다. 복합체 내 셀룰로오스의 분포는 주사전자현미경(SEM)을 통해 분석하였다. 트윈 스크류 압출기를 통해 복합체를 물리적으로 제조하였으며, 만능재료시험기(UTM)를 사용하여 인장 특성을 평가하였다. 그 결과, 개질된 셀룰로오스의 도입은 UHMWPP 복합재의 기계적 성능, 특히 연신율을 유의하게 향상시키면서도 인장 강도를 유지하는 것으로 나타났다.

Cellulose was hydrophobized using different modifier and composited with ultra-high molecular weight polypropylene (UHMWPP). The hydrophobicity was evaluated according to the type and ratio of the modifier. The UHMWPP/modified CNF composites manufactured under varying composite conditions exhibited excellent mechanical properties.

Keywords: polymer, polypropylene, ultra-high molecular weight polypropylene, modified cellulose, spay drying, compounding.

This work was supported by the Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy and Material parts technology development of KEIT, (20011130, High strength, low density UHMWPP polymer composite and impact resistance, antifriction applied product development of automotive).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

In the field of future automobile conversion R&D, the development of eco-friendly transportation systems and the lightweighting of interior and exterior materials to improve fuel efficiency are recognized as critical areas within the domain of eco-friendly convergent materials technology.1-3 A representative example is the development of composite materials that replace aluminum components, offering superior impact resistance and low specific gravity for automotive interior and exterior parts. While various polymer materials have been developed to reduce weight compared to traditional metals like steel or magnesium, these materials often suffer from lower stiffness, making the development of high-durability composite materials a key challenge.

Ultra-high molecular weight polypropylene (UHMWPP), a polypropylene-based material with significantly increased molecular weight and melt viscosity, has emerged as an innovative alternative due to its excellent mechanical durability, thermal resistance, and processability, classifying it as a general-purpose engineering plastic.4-9 The incorporation of UHMWPP into resin or rubber matrices has been shown to enhance lubricity, wear resistance, impact strength, and chemical stability, making it attractive for automotive applications such as cowl crossbeams, crash pads, and door inner panels. However, a major drawback remains-UHMWPP exhibits a higher specific gravity than conventional polypropylene, limiting its use in lightweight applications.

To overcome this limitation, this study explores the complexation of UHMWPP with nanocellulose, an emerging eco-friendly material. Cellulose, which can be abundantly derived from plants or wood, is a sustainable resource known for its low density and crystalline structure, offering strength more than eight times greater than that of stainless steel. Leveraging the superior mechanical and chemical properties of cellulose provides a pathway to enhance the performance of UHMWPP and develop environmentally friendly composite materials. Furthermore, this cellulose-reinforced composite can potentially replace conventional glass fibers and inorganic fillers used in commercial polymer composites.

While cellulose demonstrates excellent mechanical reinforcement when blended with hydrophilic polymers due to hydrogen bonding, its combination with hydrophobic polymers often results in poor compatibility caused by repulsive interactions stemming from its surface hydroxyl groups.10-16 To resolve this incompatibility, surface modification of cellulose is essential to increase hydrophobicity and enable successful integration with hydrophobic matrices like UHMWPP.

Numerous strategies have been proposed for this purpose. For instance, Bulota et al. investigated cellulose acetylation, while Mendez et al. employed maleic anhydride-grafted polypropylene.17-23 Demir et al. enhanced interfacial adhesion using silane coupling agents, and Ferreira et al. first synthesized nanocellulose with isocyanate groups before blending with polybutylene adipate terephthalate.24-27 Sunet et al. further accelerated the cellulose esterification reaction using alkaline catalysts such as NaOH and KOH.28-30 Various techniques-including esterification with monohydric alcohols, plasma treatment, and the introduction of organic functional groups -have been employed to improve the hydrophobicity of cellulose and its dispersion within polymer matrices.31-34

This study introduces two distinct surface modification strategies: (1) the introduction of terminal hydrophobic groups via urethane bonding between the hydroxyl groups on cellulose and the isocyanate groups (–NCO) of mono-isocyanate ODI; and (2) cellulose surface modification via esterification using vinyl functional groups. The research focuses on developing and evaluating UHMWPP composites incorporating these modified CNFs. Furthermore, comparative analyses were conducted to assess how the chain length of the modifiers, thermal crosslinking potential of ester groups, and the presence of vinyl versus methyl substitutions influence mechanical performance. The role of the presence or absence of double bonds was also investigated. Finally, the degree of surface modification is quantitatively and qualitatively evaluated through water contact angle measurements and dispersion analysis.

Materials. Ultra-high molecular weight polypropylene (UHMWPP, Mₙ = 1000000 g/mol; Korea Petrochemical Ind. Co., Ltd., Seoul, Korea) and cellulose nanofiber (CNF, Mₙ = 162.14 g/mol; Borregaard Co. Ltd., Hjalmar Wessels vei 6, Sarpsborg, Norway) were used as composite materials. Octadecyl isocyanate (ODI, Mₙ = 295.50 g/mol; Tokyo Chemical Industry Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) and vinyl ester (VE, Mₙ = 86.09 g/mol; Junsei Chemical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan) were used as modifiers.

Dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO, Mₙ = 78.13 g/mol; Daejung Co., Ltd., Siheung, Korea) was used as the solvent to prepare m-CNF. Deionized water, ethanol, and acetone were used as purifying agents to remove any residual reactants. For the surface modification of VE-CNF, sodium hydroxide (NaOH, Mₙ = 40 g/mol; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) was used as a catalyst to activate the hydroxyl groups in cellulose.

Filter paper with pore diameters ranging from 5 to 8 μm was used to obtain m-CNF. A field emission scanning electron microscope (FE-SEM, SUPRA 25, Carl Zeiss AG, Oberkochen, Germany) and contact angle (CA, Phoenix300, Suwon, Korea) measurements were employed to observe the morphology and confirm the hydrophobic properties of m-CNF.35-40

Characterization. Fourier transform infrared (FTIR,Spectrum two, Perkin Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA) spectroscopy was used to analyze functional groups, including hydroxyl (–OH), isocyanate (–NCO), and carbonyl (–C=O) groups, during the synthesis of ODI- and VE-modified CNF. The spectra were measured in the range of 500 to 4000 cm-1. For the powdering process, the particle size of the modified cellulose was minimized using spray drying. The tensile strength of the composites was evaluated using a universal testing machine (UTM, LS Series, AMETEK, Inc., Berwyn, IL, USA), with specimens prepared according to ASTM D638. The surface morphology of the cellulose and UHMWPP composite specimens was analyzed using a scanning electron microscope (SEM).

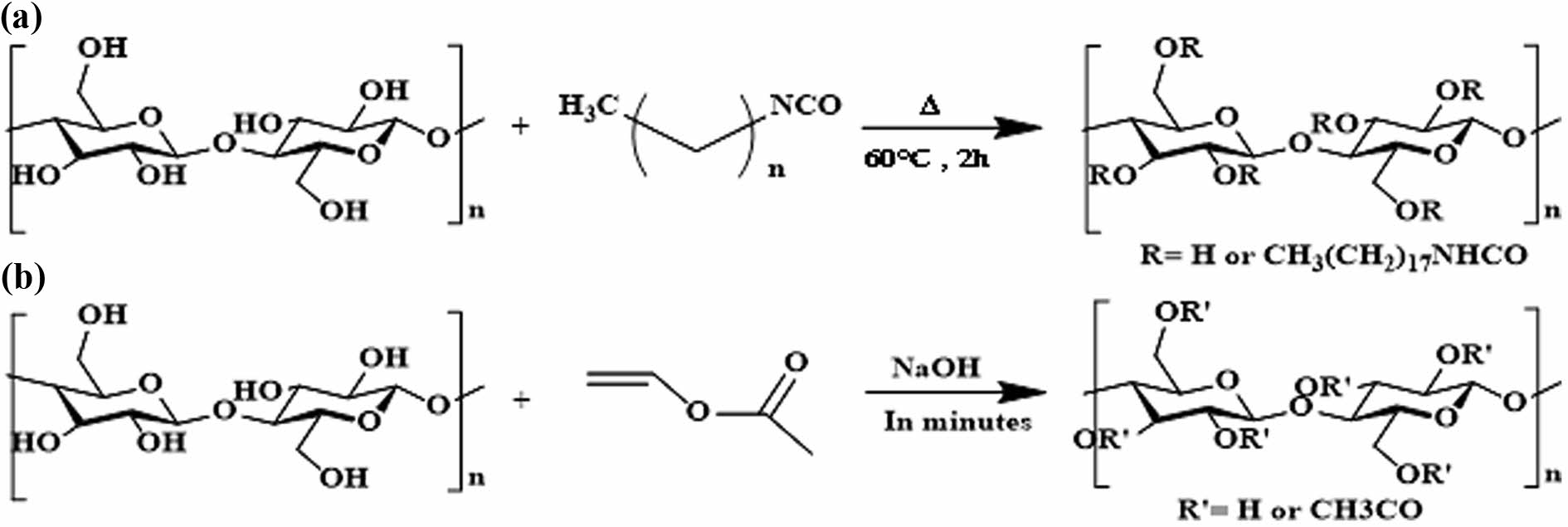

Synthesis of Modified Cellulose Fibers. Scheme 1 illustrates the synthesis of cellulose nanofibers modified with ODI and VE. A total of 400 g of paste-like cellulose nanofibers (10 wt% solid content) was added to a 5 L three-neck flask and dispersed in 1200 mL of DMSO by stirring at room temperature. After 2 h of stirring, the cellulose was fully dispersed into fibrous form, and the temperature was raised to 120 ℃ for 3 h to remove residual moisture in the paste-type cellulose. The drying process was monitored by observing the change in the hydroxyl (–OH) peak at 3300 cm-1 using FTIR; once no further change was detected, the flask temperature was lowered to 60 ℃. CNF and ODI were then reacted at a molar ratio of 1:3 and stirred at 60 ℃ for 2 h to synthesize ODI-modified CNF (ODI/m-CNF).

Scheme 1. Reaction schemes for cellulose modification: (a) urethane bonding of ODI with CNF; (b) transesterification of vinyl esters in DMSO.

Urethane bonds were formed through the reaction between the hydroxyl groups on the cellulose surface and the terminal mono-isocyanate group of ODI. After the addition of ODI, the –NCO functional group initially appeared around 2200 cm-1 in the FTIR spectrum. However, this peak disappeared in the final product, indicating complete reaction of the –NCO group. To confirm successful hydrophobization via urethane bonding, the hydroxyl (~3300 cm-1), isocyanate (~2200 cm-1), and carbonyl (~1700 cm-1) peaks were monitored by FTIR. The final product was vacuum filtered using filter paper and washed three times with acetone, then redispersed in deionized (DI) water using mechanical stirring.41-45

For VE modification, a similar procedure to that of ODI was followed. CNF was dispersed in DMSO, followed by the addition of 100 mL of NaOH solution (200 g/L) to activate the hydroxyl groups. The flask temperature was then raised to 100 ℃, and a transesterification reaction was performed using CNF and VE at a molar ratio of 1:3 for 10 min. In this base-catalyzed transesterification process, an ester and an alcohol react to form a new ester group. Under these alkaline conditions, the hydroxyl groups on the cellulose surface were substituted via nucleophilic attack by the functional groups in VE. After the reaction, 500 mL of distilled water was added to the mixture, and the FTIR spectra were monitored for the hydroxyl (~3300 cm-1) and carbonyl (~1700 cm-1) groups. The resulting product was vacuum filtered using filter paper and rinsed three times with DI water and ethanol.

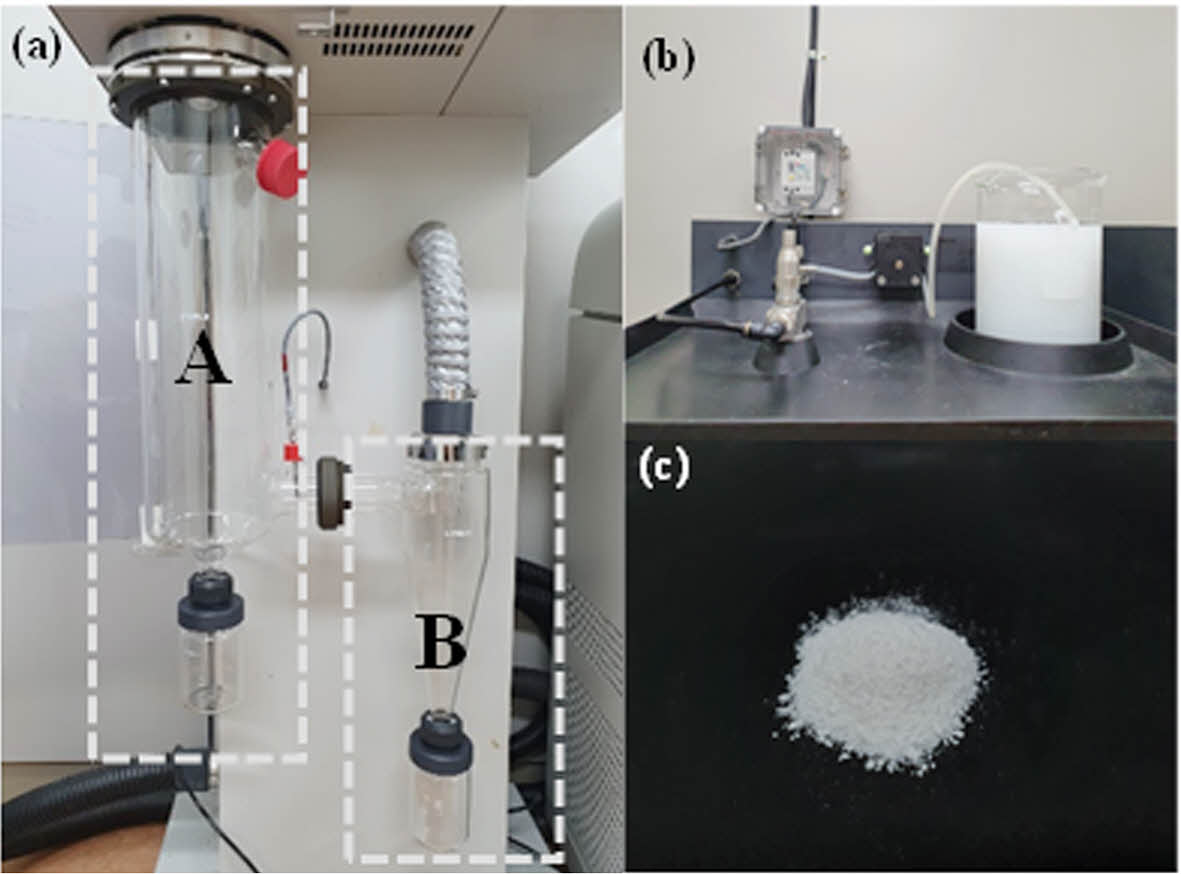

Powdering Process of Modified Cellulose Fibers. Figure 1 illustrates the spray-drying process. Figures 1(a) and 1(b) depict the powdering of m-CNF using spray drying, while Figure 1(c) shows an image of the spray-dried CNF powder in a flask containing a mixture of deionized (DI) water and CNF. In Zone A, the m-CNF is dried by applying high-temperature heat (inlet/outlet temperatures: 140 ℃ / 60 ℃) and airflow (blower: 0.53 m3/min; spray pressure: 9 × 10 kPa). In Zone B, the dried powder is collected after cooling to room temperature.

|

Figure 1 Spray drying process of m-CNF: (a–b) powderization via thermal drying (Zone A) and room-temperature cooling (Zone B); (c) spray-dried CNF powder dispersed in DI water. |

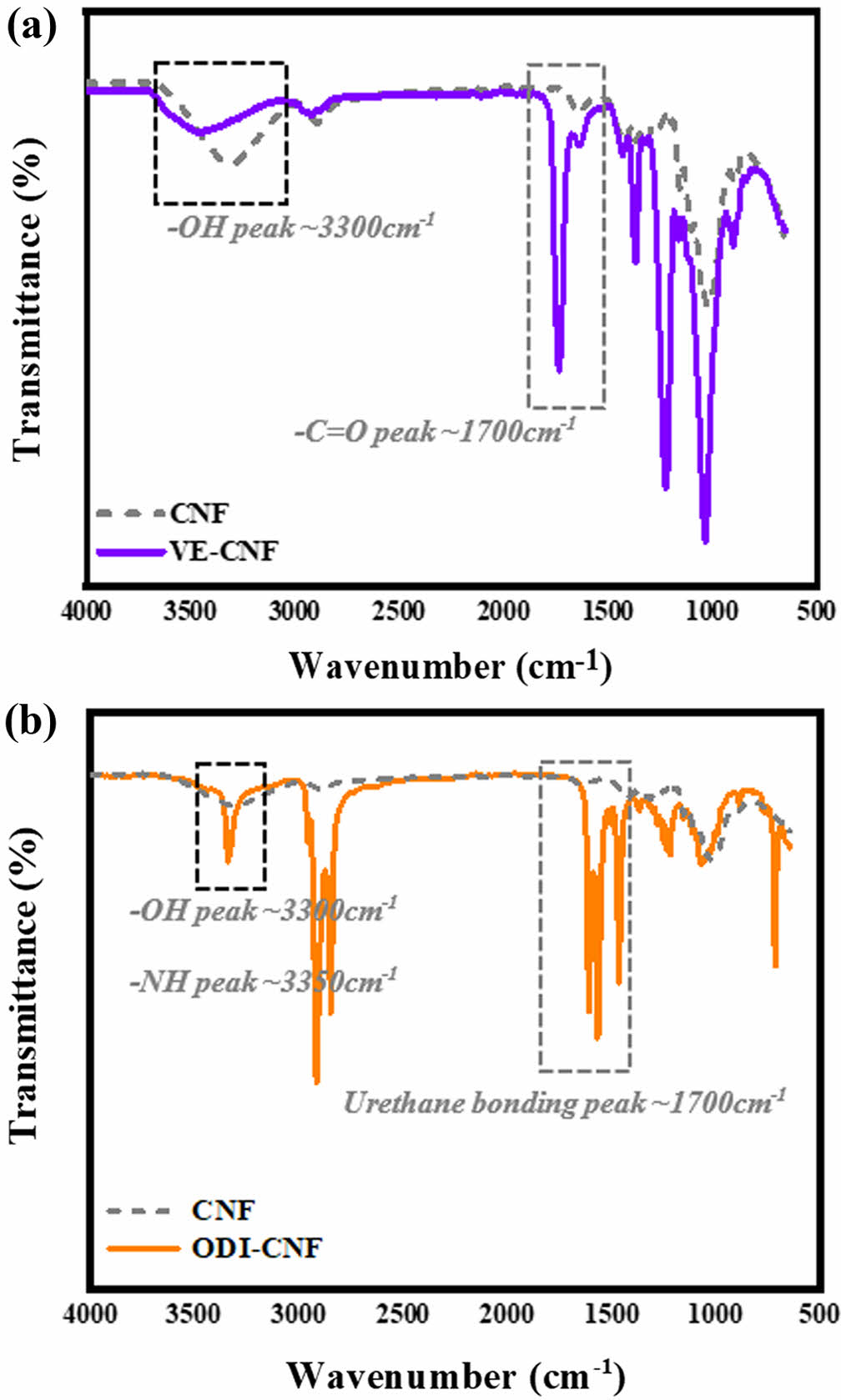

Qualitative Evaluation of Modified Cellulose Fibers. FTIR analysis was conducted to evaluate the functional group changes during the m-CNF modification process. Figure 2(a) illustrates the reaction of CNF with VE. As esterification and hydrolysis reactions occurred simultaneously, the hydroxyl groups of nanocellulose were partially replaced by ester groups. A significant reduction in the intensity of the hydroxyl group peak was observed as the reaction proceeded, indicating progress in the surface modification. However, since sodium hydroxide can degrade cellulose fibers, strict control of the reaction time is essential.46-49 Although the FTIR peak at approximately 3300 cm-1 corresponding to the –OH group decreased, it did not disappear entirely, suggesting incomplete substitution. The vinyl groups introduced onto the cellulose side chains may cause steric hindrance, leaving some residual hydroxyl groups.

Figure 2(b) shows the reaction of CNF with ODI. The mono-isocyanate groups of ODI reacted with the hydroxyl groups of cellulose, forming terminal urethane linkages that increased the hydrophobicity of the modified cellulose. As in Figure 2(a), the reduction of the hydroxyl peak and the appearance of a new –NH stretching vibration near ~3350 cm-1 were observed. Through this qualitative FTIR analysis, the hydrophobic modification of the cellulose surface and the differences between the VE and ODI treatments were successfully confirmed and compared.50-54

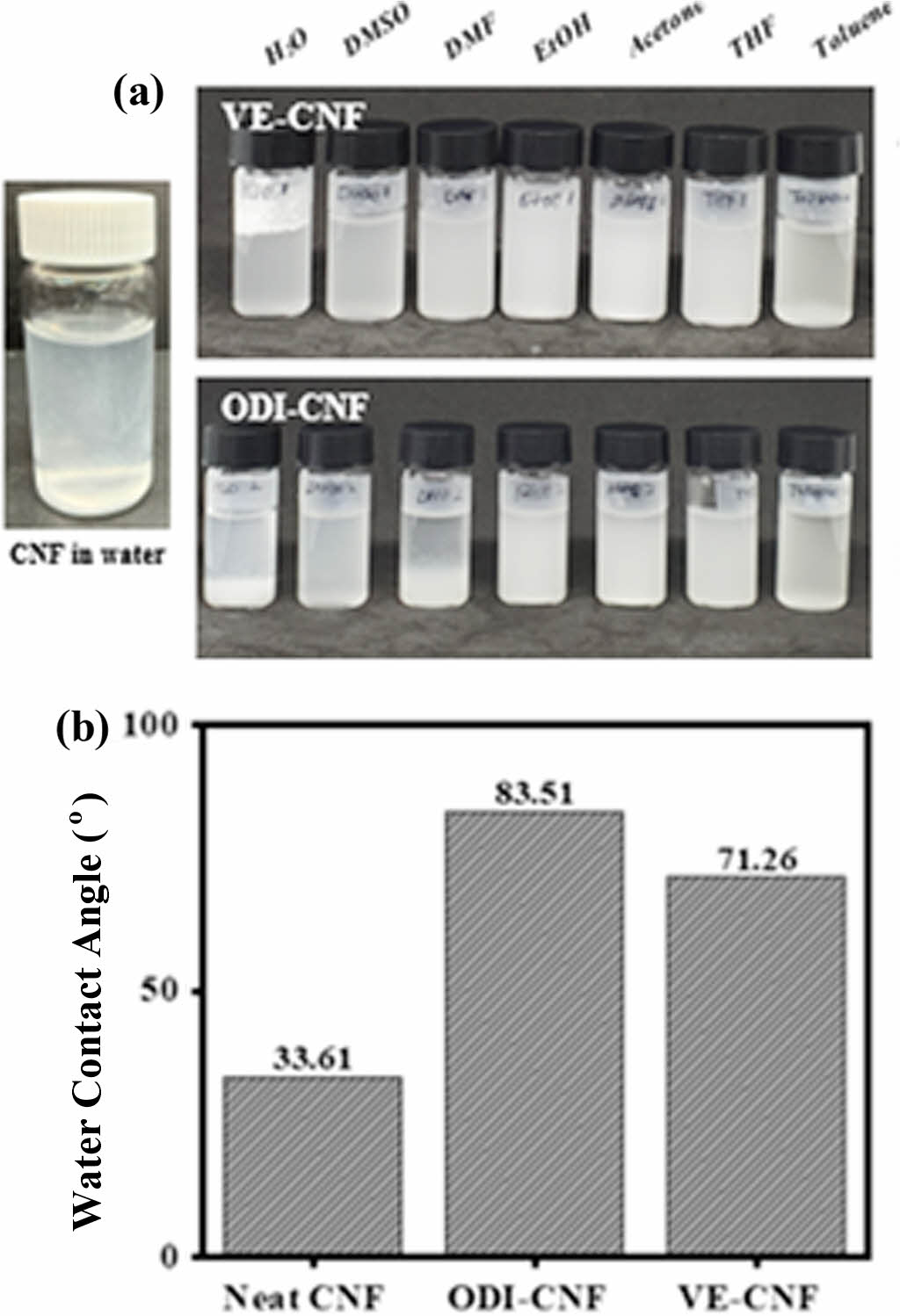

The hydrophobicity of successful m-CNF was evaluated. As shown in Figure 3(a), the image was taken 24 hours after adding 1 wt% of CNF, modified using seven solvents (H2O, dimethyl sulfoxide, dimethyl formamide, ethanol, acetone, tetrahydrofuran, toluene) and to maximize the dispersibility of cellulose, an ultrasonic dispersion process was conducted. In the case of general CNF, dispersion was best due to its good compatibility with water. Excellent dispersibility means that the particles do not clump together in the solvent but rather disperse evenly. CNF itself has very strong hydrophilic properties, so when mixed with a hydrophobic solvent, hydrogen bonds are formed between the hydroxyl groups. This phenomenon leads to aggregation. As a result, it becomes difficult for the material to express the original mechanical properties of cellulose. However, when the hydroxyl groups of CNF are partially replaced with hydrophobic functional groups, the aggregation phenomenon is reduced, and a more elongated morphology is observed. Based on this research, it was confirmed that CNF modified with ODI and VE exhibited low dispersibility in water and floated on the surface due to the hydrophobicity of the functional groups. In addition, a comparative evaluation was conducted with other organic solvents, and it was confirmed that the m-CNFexhibited a higher degree of dispersion in organic solvents compared to its behavior in water, where it either sank or floated.

Observational evaluation involves observing experimental results that can be perceived with the naked eye. To substantiate the specific research findings, the surface hydrophobicity of neat CNF and CNF modified using ODI and VE was evaluated. Figure 3(b) shows the resulting water contact angle of the m-CNF sample produced by hot pressing. Spray-dried powdered cellulose was used to produce 3/8-inch circular film form specimens using a hot press at a temperature of 180 ℃ and a pressure of 25 MPa. These specimens were then compared. It was confirmed that the contact angle of the m-CNF samples was more than twice that of pure CNF (increasing from 33.61° to 71.26° for VE-CNF, and from 33.61° to 83.51° for ODI-CNF). ODI-CNF exhibited a higher water contact angle than VE-CNF. It was confirmed that this difference was due to the influence of unreacted hydroxyl groups that remained unmodified. As a result, it was confirmed that when ODI was used as a modifier, it imparted greater hydrophobic properties than VE. ODI has an aliphatic chain form, whereas VE has a side branch structure around its chain. This difference suggests that the substitution rate of ODI is somewhat better than that of VE.

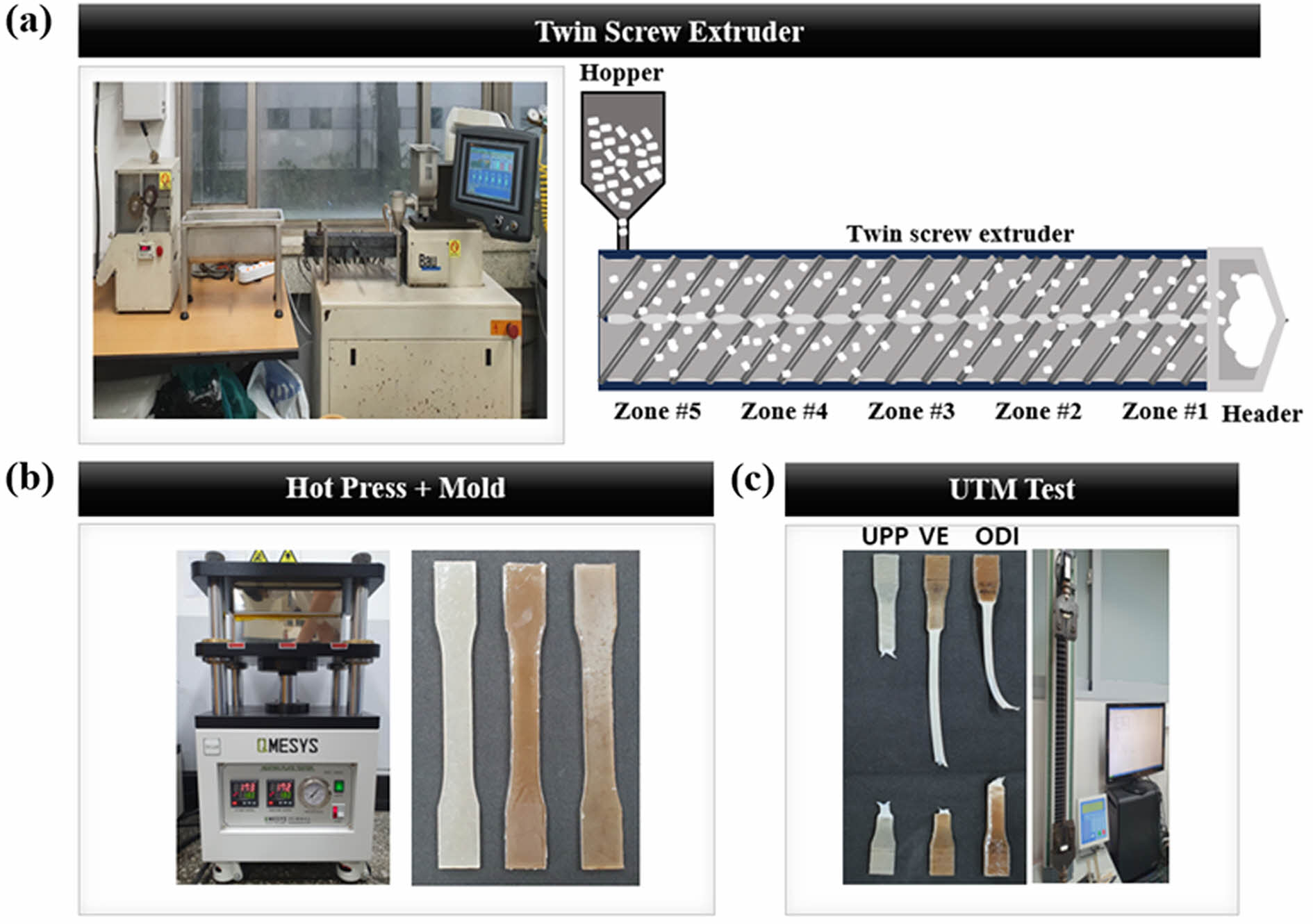

Evaluation of Mechanical Properties of Modified Cellulose Fibers. Figure 4(a) illustrates a schematic diagram of the pellet fabrication process using a twin-screw extruder and the subsequent preparation of tensile specimens using a hot press. Figure 4(b) displays the appearance of the twin-screw extruder and the specimens produced by compounding UHMWPP with m-CNF.

The UHMWPP and m-CNF powders were physically mixed and fed through the hopper of the extruder. A twin-screw extruder with a length-to-diameter (L/D) ratio of 40 was employed. The barrel temperature was set in a gradient from 180 ℃ to 210 ℃, increasing progressively from Zone #1 to the header. Specifically, the feeding zone (Zone #5), responsible for the initial melting of raw materials, was set at 180 ℃. The temperatures for Zones #4 through #1 were sequentially adjusted to 185 ℃, 190 ℃, 200 ℃, and 205 ℃ to ensure stable melt flow and prevent torque overload in the screw (with a target torque value below 6). The final header zone was set to 210 ℃ due to its narrow discharge outlet, ensuring complete extrusion of the molten UHMWPP.

The feed rate and stirring speed were controlled in the range of 80–120 rpm depending on the amount of m-CNF. It is important to note that UHMWPP undergoes thermal degradation and oxidative decomposition at temperatures exceeding 230 ℃, resulting in a significant reduction in its molecular weight below 1 million, which can negatively impact the mechanical properties of the final product.

The extruded composite strands were cut into pellets and subsequently molded into tensile specimens via hot pressing at 180 ℃ and 25 MPa, following the ASTM D638 Type I standard. The shape of the final test specimen is shown in Figure 4(b). Figure 4(c) presents the Universal Testing Machine (UTM) used to evaluate mechanical properties such as tensile strength and elongation, along with the post-test appearance of the specimens.

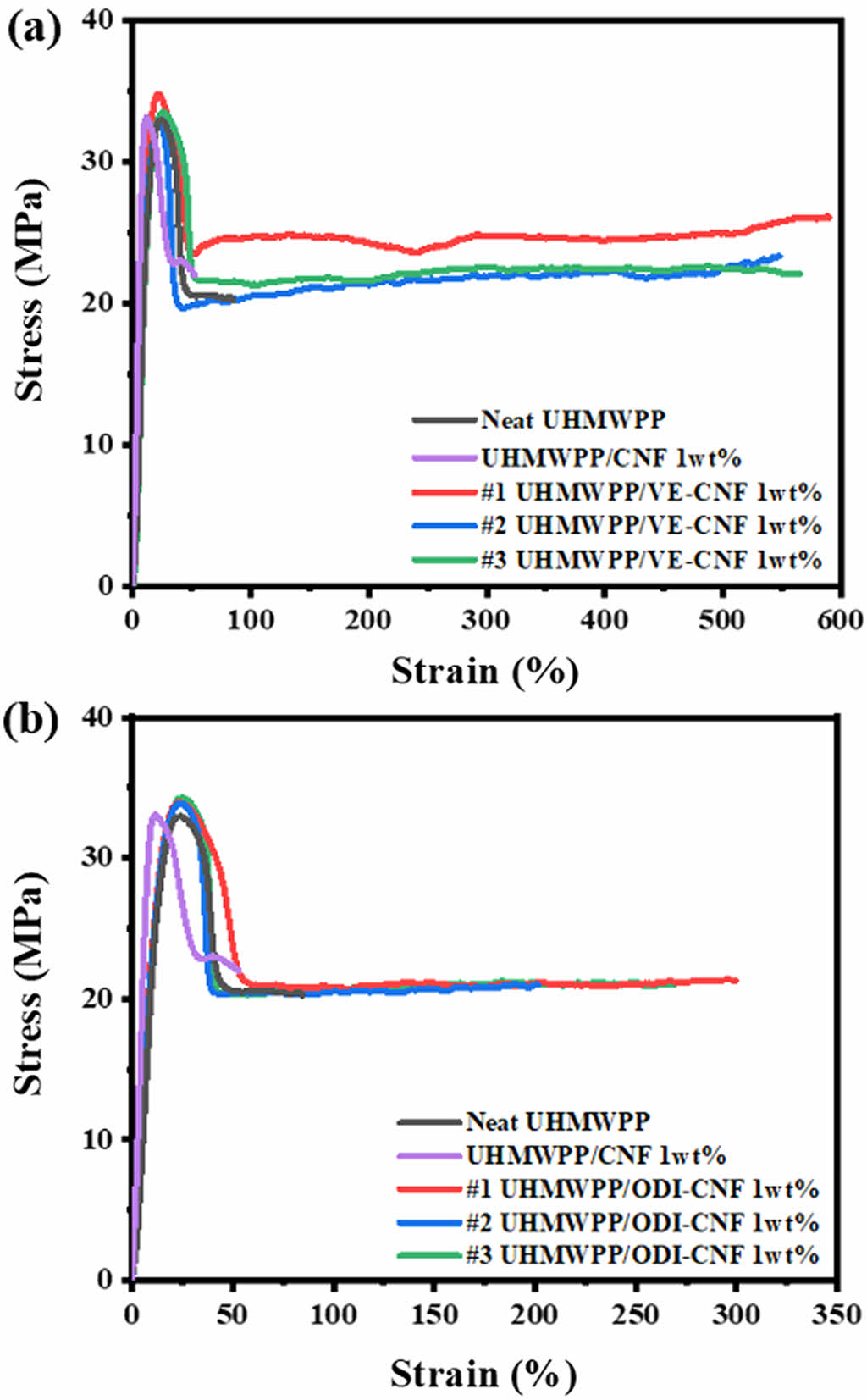

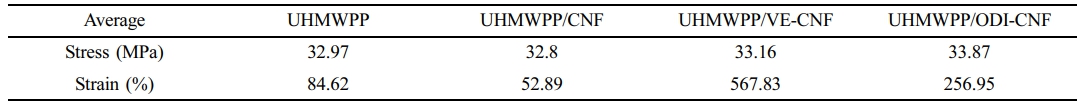

Figure 5 presents the tensile strength and elongation results of the CNF 1 wt% composites modified with ODI and VE, compared to neat UHMWPP and unmodified CNF 1 wt% composites. For the tensile strength tests, the composites with neat UHMWPP and each m-CNF variant were evaluated in triplicate, and the average values were obtained using ASTM D638 Type I dog bone specimens under a test speed of 5 mm/min. According to the measurements shown in Table 1, both neat UHMWPP and the unmodified CNF/UHMWPP composites exhibited tensile strengths in the range of approximately 32.8–39 MPa. Similarly, the composites containing 1 wt% of either ODI-CNF or VE-CNF showed comparable tensile strengths, indicating that the addition of a small amount of modified cellulose did not adversely affect the strength of the polymer matrix. These results suggest that the inherent stiffness of UHMWPP is preserved even after the incorporation of m-CNF at a low concentration, making the material design advantageous for maintaining structural performance.

However, a remarkable improvement was observed in the elongation behavior of the m-CNF composites. As shown in Figure 5(a) and 5(b), the elongation at break for the UHMWPP/ODI-CNF composite increased by approximately threefold, while the UHMWPP/VE-CNF composite showed an almost fivefold increase compared to the neat UHMWPP. When compared to the UHMWPP/unmodified CNF composite, the elongation increased by a factor of five to six, clearly demonstrating that the surface modification of CNF played a crucial role in enhancing ductility. The likely mechanism involves the replacement of the hydrophilic hydroxyl groups on cellulose with hydrophobic functional groups—long aliphatic chains in the case of ODI and terminal vinyl groups in VE—which interact more compatibly with the hydrophobic UHMWPP matrix. The hydrophobized surface minimizes interfacial repulsion, facilitates dispersion, and promotes energy dissipation during tensile loading, thereby enabling improved ductility.

Structurally, the long alkyl chain of ODI enhances compatibility during melt compounding by physically entangling with UHMWPP's molecular chains, thus improving filler-matrix interaction without compromising the matrix integrity. In contrast, VE provides a different mechanism of improvement. Although its hydrophobicity is less than that of ODI due to the presence of polar ester groups, the terminal vinyl moiety can undergo thermal crosslinking during the extrusion or pressing process. This thermal reactivity likely induces partial network formation between VE-modified CNF and the UHMWPP chains, thereby enhancing elongation through localized strain absorption and network plasticity.

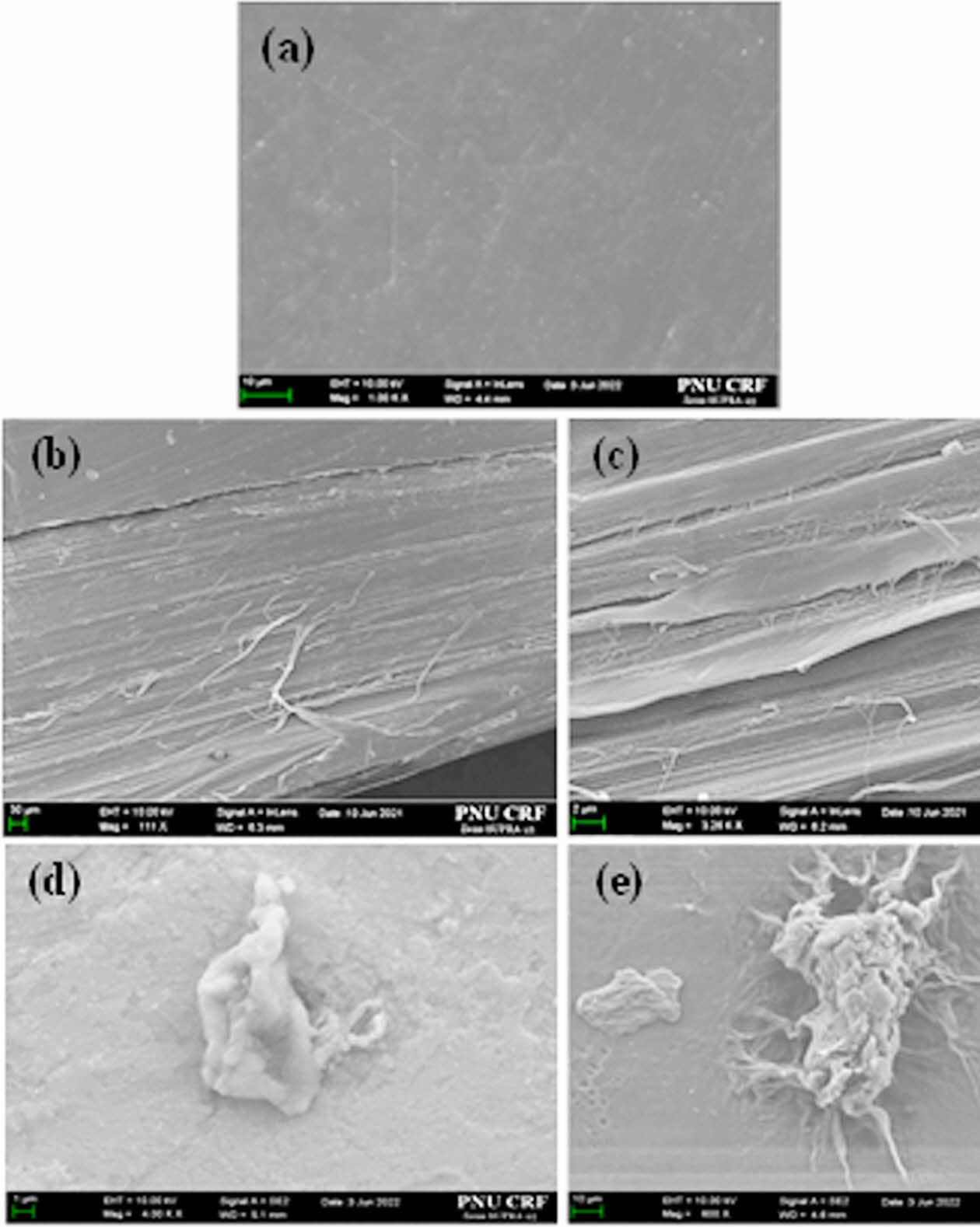

To further verify the morphological behavior of the composites, surface and cross-sectional images of the tensile specimens were analyzed using SEM, as shown in Figure 6(a)-(e). The surface of neat UHMWPP appeared flat and uniform (Figure 6(a)), while the samples containing m-CNF showed dispersed fibrous features embedded in the polymer matrix (Figures 6(d) and 6(e)). In the cross-sectional views (Figures 6(b) and 6(e)), the partial presence of m-CNF was confirmed despite the low 1 wt% content, indicating successful dispersion and integration. The relatively homogeneous distribution of the m-CNF within the UHMWPP is attributed to the improved interfacial interaction induced by hydrophobic functionalization. While unmodified CNF tends to agglomerate due to hydrogen bonding between hydroxyl groups, leading to phase separation and crack initiation, the m-CNF remains well dispersed, contributing to energy dissipation and delaying crack propagation under tensile loading. The SEM images also confirmed that the size of m-CNF remained in the micrometer range, consistent with the expected spray-dried morphology.

Overall, the incorporation of surface-modified CNF not only preserves the tensile strength of UHMWPP but also dramatically enhances its elongation. These results validate the effectiveness of surface modification using ODI and VE in improving the compatibility between cellulose and hydrophobic polymers, offering a viable strategy for producing ductility-enhanced UHMWPP composites with potential applications in lightweight and durable structural components.

|

Figure 2 FTIR spectra of surface-modified CNF: (a) VE-CNF showing –OH reduction and –C=O shift; (b) ODI-CNF showing disappearance of –NCO and urethane bond formation. |

|

Figure 3 Evaluation of hydrophobicity: (a) dispersion behavior of m-CNF in various solvents; (b) water contact angles of neat CNF, ODI-CNF, and VE-CNF. |

|

Figure 4 UHMWPP composite fabrication: (a) extrusion and pressing process; (b) composite specimen images; (c) tensile test via UTM. |

|

Figure 5 Stress–strain curves of UHMWPP composites with 1 wt% m-CNF: (a) VE-CNF; (b) ODI-CNF. |

|

Figure 6 SEM images of UHMWPP composites: (a) neat UHMWPP; (b, d) fracture surfaces with ODI-CNF; (c, e) fracture surfaces with VE-CNF. |

|

Table 1 Tensile Strength Values of UHMWPP Composites with 1 wt% CNF (unmodified and modified) |

In this study, we investigated the composite formation between ultra-high molecular weight polypropylene (UHMWPP)-a promising alternative to iron and aluminum in the automotive industry-and cellulose, which offers high strength and low specific gravity. Due to the inherent incompatibility between hydrophilic cellulose nanofibers (CNF) and the highly hydrophobic UHMWPP, surface modification was conducted to enhance interfacial compatibility. Specifically, the hydroxyl groups of CNF were hydrophobized via urethane bonding and esterification using octadecyl isocyanate (ODI) and vinyl ester (VE), respectively.

The modified cellulose (m-CNF) was dispersed in a mixed solvent of ethanol and distilled water, and unreacted monomers were removed through repeated washing and filtration. The resulting m-CNF was subsequently processed into a powder form via spray drying, yielding particles in the micrometer range. Successful modification was confirmed by spectroscopic analysis (FTIR) and solvent dispersibility evaluation, while mechanical properties were assessed to validate the composite performance.

Composites containing 1 wt% of m-CNF were homogeneously mixed with UHMWPP and exhibited improved mechanical properties compared to neat UHMWPP and UHMWPP with unmodified CNF. Notably, while both neat UHMWPP and UHMWPP/unmodified CNF composites exhibited brittle fracture behavior under tensile loading, the UHMWPP/m-CNF composites showed a clear transition to ductile fracture, indicating significantly enhanced elongation at break.

It is proposed that the terminal functional groups of the modifiers (ODI and VE) were responsible for this ductility improvement. The tensile strength of UHMWPP/VE-CNF composites remained comparable to that of neat UHMWPP (~32–33 MPa), yet the elongation increased remarkably, by approximately 3-5 times (from 84% to 567%). The improved properties of ODI-CNF are attributed to the flexible long-chain alkyl structure enhancing hydrophobic compatibility, while VE-CNF demonstrated elongation enhancement likely due to thermal crosslinking of vinyl groups during extrusion or hot pressing. This suggests that using hydrophobic modifiers with reactive double bonds can induce a transformation from brittle to ductile behavior in the polymer composite.

Unlike previous reports that emphasized increased stiffness resulting from hydrophilic CNF, this study demonstrated the feasibility of transforming rigid composites into ductile materials through CNF surface modification. These findings highlight the potential of m-CNF/UHMWPP composites for use in lightweight, high-performance applications across the automotive, marine, and structural materials industries, offering both mechanical advantages and economic value.

- 1. Mishra, R. K.; Sabu, A.; Tiwari, S. K. Materials Chemistry and the Futurist Eco-friendly Applications of Nanocellulose: Status and Prospect. J. Saudi Chem. Soc. 2018, 22, 949-978.

-

- 2. Khalid, M. Y.; Rashid, A.; Arif, Z. U.; Ahmed, W.; Arshad, H. Recent Advances in Nanocellulose-based Different Biomaterials: Types, Properties, and Emerging Applications. J. Mater. Res. Technol. 2021, 14, 2601-2623.

-

- 3. Patel, K.; Chikkali, S. H.; Sivaram, S. Ultrahigh Molecular Weight Polyethylene: Catalysis, Structure, Properties, Processing and Applications. Prog. Polym. Sci. 2020, 109, 101290.

-

- 4. Kisa, T.; Kimura, T.; Eno, A.; Janchai, K.; Yamaguchi, M.; Otsuki, Y.; Kimura, T.; Mizukawa, T.; Murakami, T.; Hato, K.; Okawa, T. Effect of Ultra-High-Molecular-Weight Molecular Chains on the Morphology, Crystallization, and Mechanical Properties of Polypropylene. Polymers 2021, 13, 4222.

-

- 5. Jiang, X.; Bin, Y.; Kikyotani, N.; Matsuo, M. Thermal, Electrical and Mechanical Properties of Ultra-high Molecular Weight Polypropylene and Carbon Filler Composites. Polym. J. 2006, 38, 419-431.

-

- 6. An, Y.; Gu, L.; Wang, Y.; Li, Y. M.; Xie, B. H.; Yang, M. B. Morphologies of Injection Molded Isotactic Polypropylene/ultra High Molecular Weight Polyethylene Blends. Mater. Design 2011, 35, 633-639.

-

- 7. Ohta, T.; Ikeda, Y.; Kishimoto, M.; Sakamoto, Y.; Kawamura, H.; Asaeda, E. The Ultra-drawing Behaviour of Ultra-high-molecular-weight Polypropylene in the Gel-like Spherulite Press Method: Influence of Solution Concentration. Polymer 1998, 39, 4739-4800.

-

- 8. Kim, B. G.; Gavande, B.; Jeong, M. K.; Kim, M. H.; Lee, W. K. Properties of Blends of Ultra-high Molecular Weight Polypropylene with Various Low Molecular Weight Polypropylenes. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 2023, 762, 63-70.

-

- 9. Kanamoto, T.; Tsuruta, A.; Tanaka, K.; Takeda, M. Ultra-High Modulus and Strength Films of High Molecular Weight Polypropylene Obtained by Drawing of Single Crystal Mats. Polym. J. 1984, 16, 75-79.

-

- 10. Yun, J. H.; Jeon, Y. J.; Kang, M. S. Prediction of the Elastic Properties of Ultra High Molecular-Weight Polyethylene Particle-Reinforced Polypropylene Composite Materials through Homogenization. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 7699.

-

- 11. Bhattacharya, A. B.; Raju, A. T.; Chatterjee, T.; Naskar, K. Development and Characterizations of Ultra-high Molecular Weight EPDM/PP Based TPV Nanocomposites for Automotive Applications. Polym. Compos. 2020, 41, 4950-4962.

-

- 12. Daniel, B.; Peder, S.; Kristina O. N. All Cellulose Nanocomposites Produced by Extrusion, J. Biobased Mater. Bioenergy 2007, 1, 367-371.

-

- 13. Jie, G.; Jun, L.; Jun, X.; Zhouyang, X.; Lihuan, M. Research on Cellulose Nanocrystals Produced From Cellulose Sources with Various Polymorphs, RSC Advances 2017, 7, 33486.

-

- 14. Sonakshi, M.; Jayaramudu, J.; Kunal, D.; Silva, M. R.; Rotimi, S.; Suprakas, S. R.; Dagang, L. Preparation and Characterization of Nano-cellulose with New Shape from Different Precursor. Carbohydr. Polym. 2013, 98, 562-567.

-

- 15. Ryu, J. H.; Youn, H. J. Effect of Sulfuric Acid Hydrolysis Condition on Yield, Particle Size and Surface Charge of Cellulose Nanocrystals. J. Korea TAPPI 2011, 43.

- 16. Fleur, R.; Bruno, V.; Nadia, E. K.; Julien, B. Nanocellulose Production by Twin-Screw Extrusion: Simulation of the Screw Profile To Increase the Productivity. Sustainable Chem. Eng. 2020, 8, 50-59.

-

- 17. Thao, T. T. H.; Kentaro, A.; Tanja, Z.; Hiroyuki, Y. Nanofibrillation of Pulp Fibers by Twin-screw Extrusion. Cellulose, 2015, 22, 421-433.

-

- 18. Wenshuai, H.; Mingzheng, W.; Fengshan, Z.; Huize, L.; Xin, X.; Faliang, L.; Ruitao, C. A Review on Nanocellulose as a Lightweight Filler of Polyolefin Composites. Carbohydr. Polym. 2020, 243, 116466.

-

- 19. Cho, E. H.; Kim, Y. H. A Study on the Compatibility of Nanocellulose-LDPE Composite. Clean Technol. 2021, 27, 124-131.

- 20. Lee, S. W.; Lee, Y. H.; Jho, J. Y. Polypropylene Composite with Aminated Cellulose Nanocrystal. Polym. Korea 2020, 44, 734-740.

-

- 21. Andresen, M.; Johansson, L. S.; Tanem, B. S.; Stenius, P. Properties and Characterization of Hydrophobized Microfibrillated Cellulose. Cellulose 2006, 13, 665-677.

-

- 22. Reverdy, C.; Belgacem, N.; Moghaddam, M. S.; Sundin, M.; Swerin, A.; Baras, J. One-step Superhydrophobic Coating Using Hydrophobized Cellulose Nanofibrils. Colloids Surf. A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2018, 544, 152-158.

-

- 23. Nigmatullin, R.; Johns, M. A.; Muñoz-García, J. C.; Gabrielli, V.; Schmitt, J.; Angulo, J.; Khimyak, J. A.; Scott, J. L.; Edier, K. J.; Eichhorn, S. J. Hydrophobization of Cellulose Nanocrystals for Aqueous Colloidal Suspensions and Gels. Biomacromolecules 2020, 21, 1812-1823.

-

- 24. Cichosz, S.; Masek, A. Cellulose Fibers Hydrophobization via a Hybrid Chemical Modification. Polymers 2019, 11, 1174.

-

- 25. Sabzalian, Z.; Alam, M. N.; Van de Ven, T. G. M. Hydrophobization and Characterization of Internally Crosslink-reinforced Cellulose Fibers. Cellulose 2014, 21, 1381-1393.

-

- 26. Chang, C.; Zhang, L. Cellulose-based Hydrogels: Present Status and Application Prospects. Carbohydr. Polym. 2011, 84, 40-53.

-

- 27. Demirbas, A. Biomass Resource Facilities and Biomass Conversion, Processing for Fuels and Chemicals. Energy Convers. Manage. 2001, 42, 1357-1378.

-

- 28. Klemm, D.; Heublein, B.; Fink, H.-P.; Bohn, A. Cellulose: Fascinating biopolymer and dustainable raw material. Angew. Chem., Int. Ed. 2005, 44, 3358-3393.

-

- 29. Ma, F.; Hanna, M. A. Biodiesel Production: A Review. Bioresour. Technol. 1999, 70, 1-15.

- 30. Rooney, M. L. Interesterification of Starch with Methyl Palmitate. Polymer. 1976, 17, 555-558.

-

- 31. Ferreira, L.; Gil, M. H.; Dordick, J. S. Enzymatic Synthesis of Dextran-containing Hydrogels. Biomaterials. 2002, 23, 3957-3967.

-

- 32. Dicke, R. A Straight Way to Regioselectively Functionalized Polysaccharide Esters. Cellulose. 2004, 11, 255-263.

-

- 33. Heinze, T.; Dicke, R.; Koschella, A.; Kull, A. H.; Klohr, E. A.; Koch, W. Effective Preparation of Cellulose Derivatives in a New Simple Cellulose Solvent. Macromol. Chem. Phys. 2000, 201, 627-631.

-

- 34. Xie, J.; Hsieh, Y.-L. Enzyme-catalyzed Transesterification of Vinyl Esters on Cellulose Solids. J. Polym. Sci. Part A: Polym. Chem. 2001, 39, 1931-1939.

-

- 35. Çetin, N. S.; Tingaut, P.; Özmen, N.; Henry, N.; Harper, D.; Dadmun, M.; Sebe, G. Acetylation of Cellulose Nanowhiskers with vinyíacetate under moderate conditions. Macromol. Biosci. 2009, 9, 997-1003.

-

- 36. Meher, L. C.; Vidya Sagar, D.; Naik, S. N. Technical Aspects of Biodiesel Production by Transesterification-A Review. Renewable Sustainable Energy Rev. 2006, 10, 248-268.

-

- 37. Adachi, S.; Kobayashi, T. Synthesis of Esters by Immobilized Lipase Catalyzed Condensation Reaction of Sugars and Fatty Acids in Watermiscible Organic Solvent. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2005, 99, 87-94.

-

- 38. Liu, Y.; Hu, H. X-ray Diffraction Study of Bamboo Fibers Treated with NaOH. Fibers Polym. 2008, 9, 735-739.

-

- 39. Schilling, M.; Bouchard, M.; Khanjian, H.; Learner, T.; Phenix, A.; Rivenc, R. Application of Chemical and Thermal Analysis Methods for Studying Cellulose Ester Plastics. Acc. Chem. Res. 2010, 43, 888-896.

-

- 40. Maim, C. J.; Mench, J. W.; Kendall, D. L.; Hiatt, G. D. Aliphatic Acid Esters of Cellulose: Properties. Ind. Eng. Chem. 1951, 43, 688-691.

-

- 41. Karim, M.; Mohamed, N. B.; Julien, B. Nanofibrillated Cellulose Surface Modification: A Review. Materials. 2013, 6, 1745-1766.

-

- 42. Siqueira, G.; Bras, J.; Dufresne, A. Luffa Cylindrica as a Lignocellulosic Source of Fiber, Microfibrillated Cellulose, and Cellulose Nanocrystals. BioResources. 2010, 5, 727-740.

-

- 43. Lavoine, N.; Desloges, I.; Dufresne, A.; Bras, J. Microfibrillated Cellulose—Its Barrier Properties and Applications in Cellulosic Materials: A Review. Carbohydr. Polym. 2012, 90, 735-764.

-

- 44. Henriksson, M.; Henriksson, G.; Berglund, L. A.; Lindström, T. An Environmentally Friendly Method for Enzyme-assisted Preparation of Microfibrillated Cellulose (MFC) Nanofibers. Eur. Polym. J. 2007, 43, 3434-3441.

-

- 45. Werbowyj, R. S.; Gray, D. G. Mol. Cryst. Liq. Cryst. 1976, 34, 97-103.

- 46. Siqueira, G.; Tapin-Lingua, S.; Bras, J.; da Silva Perez, D.; Dufresne, A. Morphological Investigation of Anoparticles Obtained from Combined Mechanical Shearing, and Enzymatic and Acid Hydrolysis of Sisal Fibers. Cellulose. 2010, 17, 1147-1158.

-

- 47. Bulota, M.; Kreitsmann, K.; Hughes, M.; Paltakari, J. Acetylated Microfibrillated Cellulose as a Toughening Agent in Poly(lactic acid). Appl. Polym. 2012, 126, E449-E458.

-

- 48. Ortega, H. O.; Reixach, R.; Espinach, F. X.; Mendez, J. A. Maleic Anhydride Polylactic Acid Coupling Agent Prepared from Solvent Reaction: Synthesis, Characterization and Composite Performance. Materials. 2022, 15, 1161.

-

- 49. Demir, H.; Atikler, U.; Balkose, D.; Tuhminlioglu, F. The Effect of Fiber Surface Treatments on the Tensile and Water Sorption Properties of Polypropylene–luffa Fiber Composites. Compos. Part A Appl. Sci. Manuf. 2006, 37, 447-456.

-

- 50. Pinheiro, I. F.; Ferreira, F. V.; Souza, R. F.; Gouveia, R. F.; Lona, L. M. F.; Morales, A. R.; Mei, L. H. I. Mechanical, Rheological and Degradation Properties of PBAT Nanocomposites Reinforced by Functionalized Cellulose Nanocrystals. Europ. Polym. J. 2017, 97, 356-365.

-

- 51. Cao, X.; Sun, S.; peng, X.; Zhong, L.; Sun, R.; Jiang, D. Rapid Synthesis of Cellulose Esters by Transesterification of Cellulose with Vinyl Esters under the Catalysis of NaOH or KOH in DMSO. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2013, 61, 2489-2495.

-

- 52. Liu, Y.; Wang, B.; Chen, J.; Zhu, M.; Jiang, Z. Flexible Nanofiber Pressure Sensors with Hydrophobic Properties for Wearable Electronics. Materials. 2024, 17, 2463.

-

- 53. Jang, N. S.; Noh, C. H.; Kim, Y. H.; Yang, H. J.; Lee, H. G.; Oh, H. S. Evaluation of a Hydrophobic Coating Agent Based on Cellulose Nanofiber and Alkyl Ketone Dimer. Materials. 2023, 16, 4216.

-

- 54. Siró, I.; Plackett, D. Microfibrillated Cellulose and New Nanocomposite Materials: A Review. Cellulose 2010, 17, 459-494.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(6): 700-708

Published online Nov 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.6.700

- Received on Jan 23, 2025

- Revised on Jun 15, 2025

- Accepted on Jul 6, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Ji-Hong Bae* , and PilHo Huh

-

Department of Polymer Science and Engineering, Pusan National University, Busan 609-735, Korea

*Research Institute of Industrial Technology, Pusan National University, Busan 609-735, Korea - E-mail: jhbae@pusan.ac.kr, pilho.huh@pusan.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0003-1605-7063, 0000-0001-9484-8798

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.