- Surface Modification on Nano-TiO2 with PANi/Phytic Acid for Enhanced Photocatalytic Performance

Department of Bio-chemical Engineering, Chosun University, Chosundaegil 146, Dong-gu, Gwangju 61452, Korea

- 폴리아닐린/피트산 기반 표면 개질을 통한 나노 TiO2의 광촉매 특성

조선대학교 생명화학공학과

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

This study presents an innovative and environmentally sustainable approach to enhancing the photocatalytic performance of nano-TiO2 via surface modification with polyaniline (PANi) and phytic acid. Immersion of Nano-TiO2 electrodes in a highly diluted PANi/phytic acid solution allowed -H2PO4 groups to form hydrogen bonds with the TiO2 surface and simultaneously crosslink with aniline monomers, resulting in a conformal, conductive thin layer. This interfacial structure significantly improved electrode stability. Furthermore, electrostatic interactions between negatively charged TiO2 and positively charged PANi facilitated efficient charge transfer, forming a robust conductive network around the TiO2 particles. The PANi/phytic acid-modified Nano-TiO2 exhibited enhanced photocatalytic activity and electrochemical durability, effectively addressing the limitations of conventional TiO2, including poor charge separation and limited light utilization. This composite demonstrates strong potential as a scalable, low-cost platform for solar-driven hydrogen production, contributing to the advancement of sustainable and renewable energy technologies.

본 연구에서는 폴리아닐린(PANi)과 피트산(phytic acid)을 이용한 나노 TiO2의 표면 개질을 통해 광촉매 성능을 향상시키는 새로운 친환경적 접근법을 제시한다. 나노 TiO2 전극을 희석된 PANi/피트산 용액에 침지함으로써, -H2PO4 기는 TiO2 표면과 수소 결합을 형성하는 동시에 아닐린 단량체와 가교되어 균일한 전도성 박막을 형성하였다. 이 계면 구조는 전극의 안정성을 크게 향상시켰으며, 음전하를 띠는 TiO2와 양전하를 띠는 PANi 간의 정전기적 상호작용은 효율적인 전하 전달을 촉진하여 견고한 전도성 네트워크를 구축하였다. 그 결과, PANi/피트산으로 개질된 나노 TiO2는 향상된 광촉매 활성과 우수한 전기화학적 내구성을 나타내었으며, 이는 기존 TiO2의 낮은 전하 분리 효율 및 제한적인 광 활용성을 효과적으로 극복하였다. 본 복합체는 태양광 기반 수소 생산을 위한 저비용 및 대규모 적용 가능 플랫폼으로서 높은 잠재력을 지니며, 지속가능한 재생에너지 기술 발전에 기여할 수 있을 것으로 기대된다.

Enhanced TiO2 photocatalytic performance via polyaniline (PANi)/phytic acid integration for improved electron transfer and stability. 200D PANi/phytic acid electrodes showed superior photocurrent, stability, and low charge-transfer resistance. Promotes sustainable solar-driven hydrogen production, advancing renewable energy solutions.

Keywords: photocatalyst, polyaniline, phytic acid, water splitting, hydrogen.

This research was supported by the Regional Innovation System & Education (RISE) program through the (Gwangju RISE Center), funded by the Ministry of Education (MOE) and the (Gwangju Metropolitan City), Republic of Korea. (2025-RISE-05-013)

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Global industrialization and its dependence on nonrenewable energy sources have significantly elevated greenhouse gas emissions, accelerated global warming, and contributed to widespread environmental degradation.1-4 CO2 emissions from fossil fuels are expected to increase by 50% by 2050, further exacerbating severe environmental issues including biodiversity loss, prolonged droughts, catastrophic floods, rampant wildfires, ocean acidification, polar ice melting, and rising sea levels. In response to this crisis, the 2015 Paris Agreement, endorsed by 197 nations, established a global framework for coordinated climate action beyond 2020. Achieving the objectives of the Agreement requires reducing CO2 emissions and actively removing atmospheric CO2. Achieving net-zero or even negative emissions necessitates the implementation of multifaceted strategies that span the social, economic, environmental, and technological domains, with a strong focus on adopting renewable energy, improving energy efficiency, and developing innovative carbon mitigation technologies. Technological and industrial innovations play a pivotal role in advancing climate strategies.5 Key measures include reducing the overall energy consumption, accelerating the transition to renewable energy sources, minimizing dependence on fossil fuel-derived carbon, and emphasizing waste recycling and reuse. Among these strategies, the transition to renewable energy resources, including biomass, hydropower, hydrogen, geothermal, solar, wind, and marine energies, is widely regarded as the most direct and effective pathway for mitigating carbon emissions and addressing global climate challenges. These resources are categorized as primary, domestic, and environmentally sustainable, and provide clean and inexhaustible alternatives to conventional energy sources.6-9

Among the renewable energy options, hydrogen stands out because of its high specific energy density, delivering approximately three times the energy output of gasoline combustion per unit mass. Moreover, hydrogen can be produced from diverse feedstocks including water, oil, natural gas, biofuels, and sewage sludge, offering flexibility in production methods. Further, water is an abundant and globally available resource that provides a sustainable pathway for hydrogen production and ensures long-term viability.10,11

Currently, hydrogen is predominantly produced through the steam reforming of natural gas and coal gasification. Although efficient, these methods rely on finite resources and emit significant amounts of CO2. A more environmentally friendly approach involves the direct extraction of hydrogen from water molecules, which generates no harmful byproducts. However, this reaction is thermodynamically demanding and requires a substantial energy input.12,13 Water electrolysis powered by renewable energy sources such as hydropower, wind, or solar energy has been explored as a green method for hydrogen production.14,15 Although effective, these methods have high operational costs and limited efficiency. An alternative approach involves utilizing solar energy, which is an abundant and universally accessible resource, to directly photolyze water molecules. By emulating the natural photosynthetic processes, this method offers a straightforward and cost-effective route for converting solar energy into hydrogen.16,17

The first successful demonstration of water splitting into hydrogen and oxygen by Fujishima and Honda in 1972, using TiO2 as a photocatalyst under UV light, spurred extensive research into semiconductors for solar-driven water photoelectrolysis. Despite the ongoing exploration of alternative materials, TiO2 remains a highly favored photocatalyst owing to its advantageous properties including nontoxicity, abundance, affordability, chemical stability, and exceptional photocatalytic performance. Furthermore, its adaptability for nanostructuring into diverse morphologies, such as porous structures, nanosheets, fibers, and nanotubes, has established its role in applications such as water splitting, pollutant degradation, photovoltaics, energy storage, and pigments.18,19 However, TiO2 has limitations in photocatalytic applications. Its wide bandgap (2.6~3.4 eV) restricts light absorption to the UV spectrum, which comprises only a small fraction of the solar spectrum.20 Additionally, the rapid recombination of charge carriers reduces the overall efficiency. Addressing these challenges requires the development of innovative semiconductor designs with optimized band structures, broad spectral sensitivities, and high operational stabilities.21,22

To overcome these challenges, researchers have explored a range of modification techniques, such as doping TiO2 with metals or non-metals, depositing noble metals, creating composites with narrow-bandgap semiconductors, and sensitizing them with dyes. Recently, π-conjugated polymers have emerged as a promising alternative, given their ability to absorb visible light effectively, their high electrical conductivity, and their efficient charge transfer capabilities. Among these materials, polyaniline (PANi) is notable for its ability to enhance the electronic and photocatalytic properties of TiO2. In addition, its simple and cost-effective synthesis, as well as its exceptional environmental stability, make PANi a compelling option for developing high-performance and eco-friendly TiO2-based photocatalytic systems.23-25

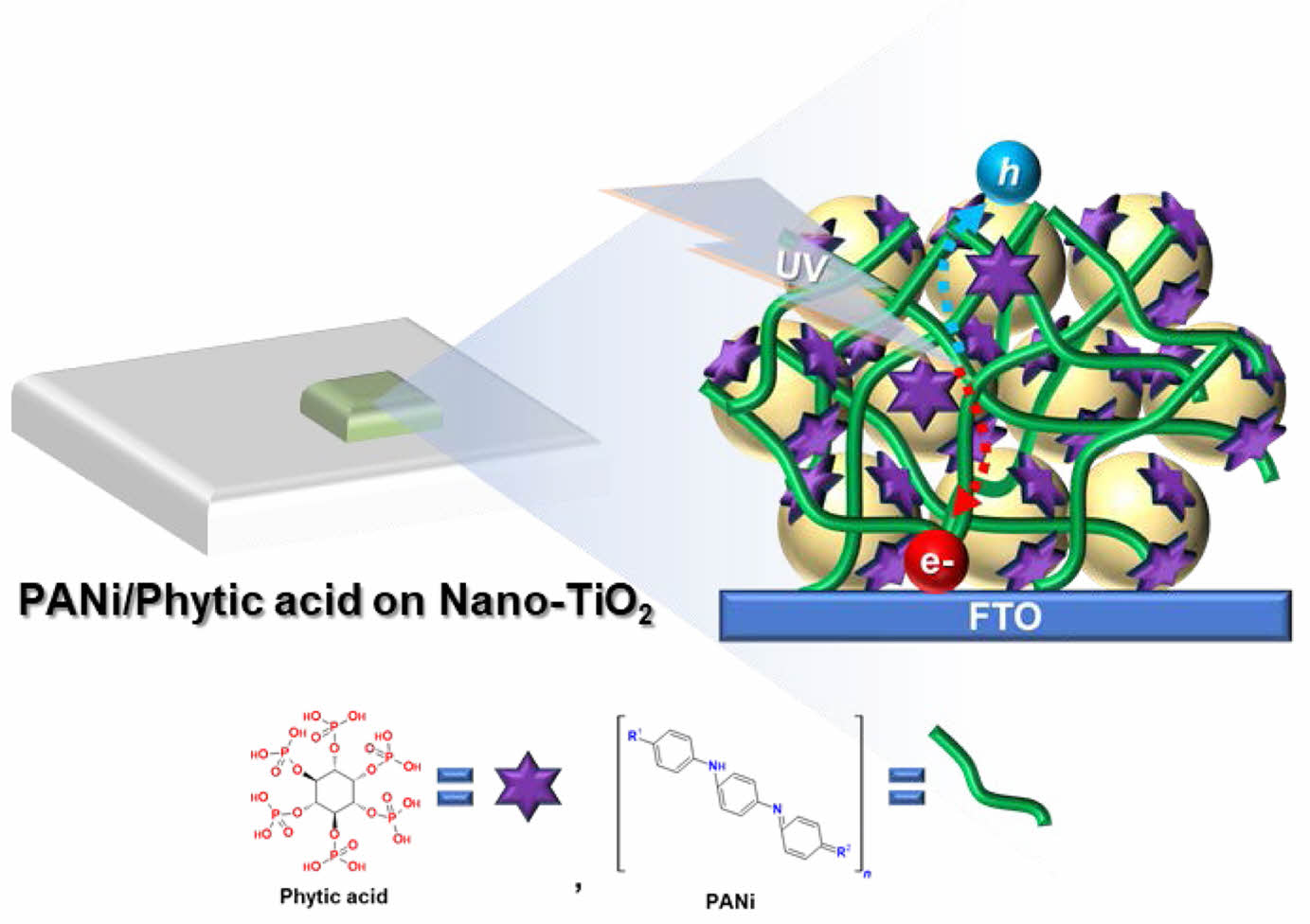

This study demonstrates the synthesis of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 surfaces using a simple, cost-efficient, and environmentally friendly method aimed at improving photo-catalytic performance. During the direct polymerization process, the immersion of the Nano-TiO2 electrodes in a highly dilute solution enabled the -H2PO4 groups in the phytic acid structure to partially form hydrogen bonds with the Nano-TiO2 surface, significantly enhancing cycling stability.26 This interaction facilitated the development of a uniform phytic acid coating, which subsequently crosslinked with aniline monomers during polymerization to form a partial conductive layer. In addition, the negatively charged Nano-TiO2 surface likely engaged in electrostatic interactions with the positively charged PANi doped with phytic acid. The robust bicontinuous conductive network resulting from these interactions encapsulates the TiO2 particles, thereby enhancing both photocatalytic activity and cycling stability. The integration of PANi/phytic acid into Nano-TiO2 represents a significant advancement in the development of high-performance photocatalytic systems.

Specifically, by addressing the intrinsic limitations of TiO2 and harnessing the complementary properties of PANi, an ecofriendly and efficient solution involving so-lar-driven water splitting is achieved for hydrogen generation. These findings contribute to the broader goals of advancing renewable energy technologies and mitigating the impacts of climate change.

Materials. TiO2 paste (Ti-Nanoxide T/SP) was supplied by Solaronix; phytic acid (50 wt% in water), aniline (ACS reagent, ³ 99.5%), ammonium persulfate (ACS reagent, ³ 98.0%), fluorine doped tin oxide coated glass (FTO glass, ~ 8 Ω/sq) and titanium (IV) chloride (TiCl4, 99.9% trace metals basis) by Sigma Aldrich. All chemicals were used without additional purification.

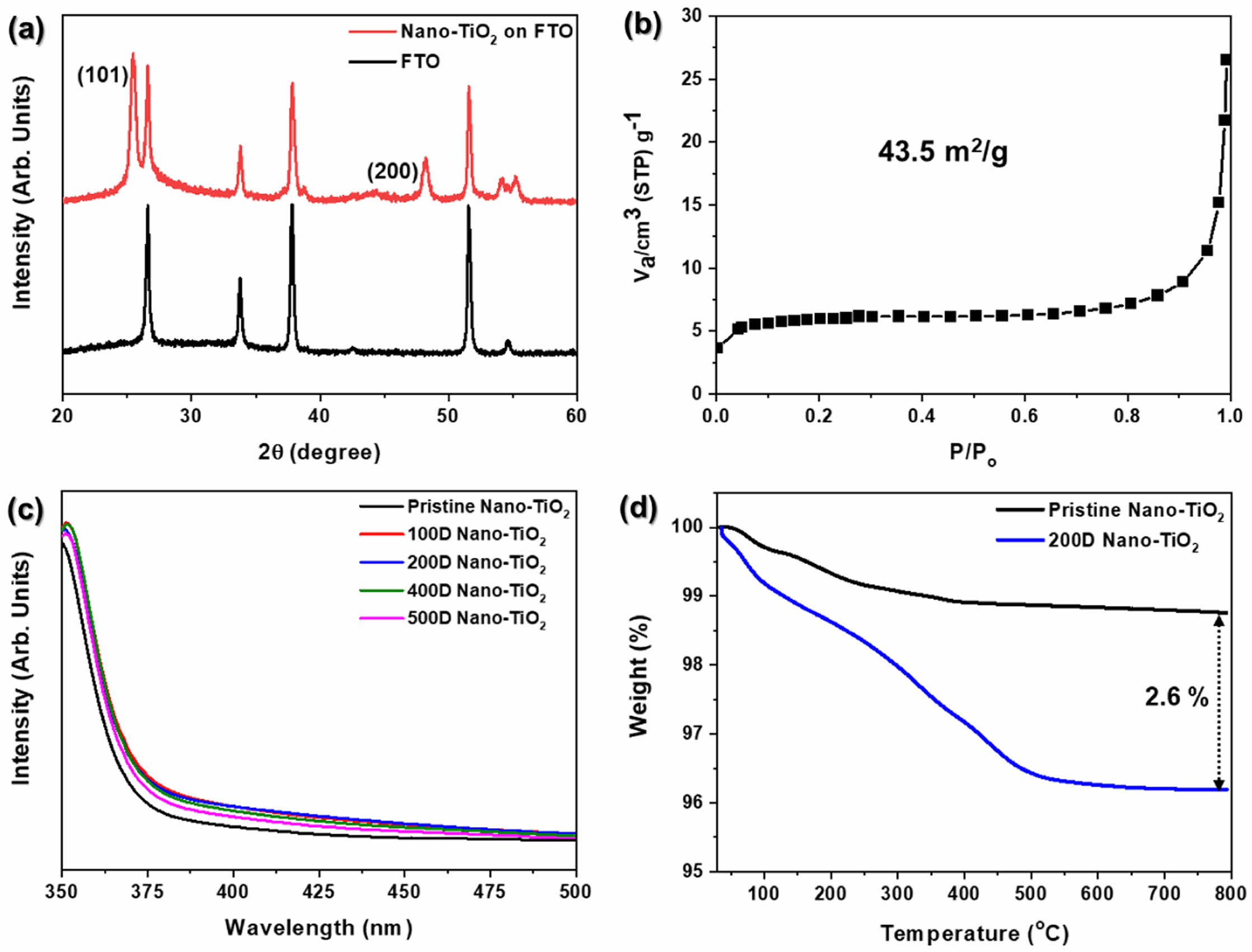

Preparation for PANi/phytic Acid on Nano-TiO2 Electrode. An FTO glass substrate pretreated with O2 plasma was immersed in a 40 mM aqueous TiCl4 solution at 70 ℃ for 30 min, followed by rinsing with deionized water and ethanol. Subsequently, a layer of nanocrystalline TiO2 (Solaronix Ti–nano oxide T/SP) was applied to the FTO substrate, which was then dried at 120 ℃ for 5 min. The resulting films were then annealed at 500 ℃ for 10 min. This process (paste application, drying, and annealing) was repeated until the electrode attained the desired thickness.

A Nano-TiO2 coated FTO glass substrate was immersed in 5 mL of a reaction solution containing 50 mM aniline monomer and 40 mM phytic acid for 1 h. Subsequently, 0.2 mL of an initiator solution consisting of 125 mM ammonium persulfate was added to the mixture. A color change from brown to dark green was observed within minutes, indicating the successful polymerization of the aniline monomers to form PANi/phytic acid. To achieve a thin layer, the two solutions were diluted 100, 200, 400, and 500 times their original concentrations before performing subsequent experiments. The samples were designated based on the degree of dilution of the reaction solution as follows: Pristine TiO2 (undiluted), 100D Nano-TiO2 (diluted 100 times), 200D Nano-TiO2 (diluted 200 times), 400D Nano-TiO2 (diluted 400 times) and 500D Nano-TiO2 (diluted 500 times).

Characterization. Morphological analysis was performed using field-emission scanning electron microscopy (FE-SEM; S-4800, Hitachi Corp., Japan) and field-emission transmission electron microscopy (FE-TEM, Tecnai G2 F20 X-Twin, FEI), X-ray diffraction spectrometry (Normal XRD, D8 Advance, Bruker AXS, Billerica, MA, USA, with Cu Kα radiation). The structural characteristics were examined using Fourier-transform infrared spectroscopy (FTIR, Nicolet 6700, Thermo Scientific Corp., USA), X-ray diffraction (XRD, MXD10, Rigaku Corp., Japan), and laser scanning confocal micro-Raman spectroscopy (AFM-Raman, Alpha300s, WITec Corp., Germany). The thermal properties were evaluated by thermogravimetric analysis (TGA) using a TGA2050 instrument (TA Instruments, USA). The specific surface area was analyzed using nitrogen adsorption–desorption isotherms (ASAP 2420 instrument, Micromeritics at 77 K, Norcross, GA, USA).

Photoelectrochemical (PEC) Characterization. The photoelectrochemical (PEC) performance of the Nano-TiO2 electrodes was analyzed using a three-electrode configuration under front-side illumination with simulated AM 1.5 G sunlight. A Ag/AgCl electrode and platinum mesh were used as the reference and counter electrodes, respectively, and 1 M NaOH served as the electrolyte. The exposed area of the working electrode was precisely controlled to 1.5 cm2 using a scotch tape. Photocurrent stability was evaluated by monitoring the photocurrent response under chopped light irradiation with alternating 10-second light and dark cycles. Electrochemical impedance spectroscopy (EIS) was performed over a frequency range of 100 kHz to 0.1 Hz using a potentiostat at the open circuit potential under illumination.

To prepare the substrate, FTO glass was first thoroughly washed and pre-treated with O2 plasma to produce a clean, highly wettable surface. This step was critical for removing surface contaminants and ensuring optimal conditions for subsequent coating processes. The cleaned substrate was then immersed in a 40 mM aqueous TiCl4 solution at 70 ℃ for 30 min, followed by careful rinsing with deionized water and ethanol to remove residual TiCl4. This mild treatment facilitated the homogeneous deposition of a Nano-TiO2 layer on the FTO surface, significantly enhancing adhesion. This enhancement ensured the durability and reliability of the electrode in later applications.

A TiO2 paste (Ti-Nanoxide T/SP) was uniformly applied to the TiCl4-treated FTO glass substrate using a precise coating technique to achieve an even distribution across the surface, as described in earlier studies.27,28 The coated substrate was then dried at 120 ℃ for 5 min in a controlled manner to prevent structural collapse or cracking within the TiO2 film. Following this drying process, the Nano-TiO2 film was annealed at 500 ℃ for 10 min under a controlled atmosphere to improve the crystallinity of the TiO2 particles, enhance adhesion to the substrate, and improve mechanical stability. This sequence of paste deposition, drying, and annealing was repeated multiple times to incrementally build the thickness of electrode to the desired level without compromising its structural uniformity or integrity.

The TiO2-coated FTO glass substrate was then immersed in 5 mL of a reaction solution containing 50 mM aniline monomer and 40 mM phytic acid for 1 h. This process facilitated the interaction between the Nano-TiO2 surface and the reactants. Phosphate groups within the phytic acid were thought to interact with the TiO2 surface via hydrogen bonding, aiding the polymerization process and enhancing the adhesion between the Nano-TiO2 substrate and the developing polymer layer. These interactions contributed to the improved structural integrity and stability of the resulting composite material.

Following the immersion step, 0.2 mL of an initiator solution containing 125 mM ammonium persulfate was added to the reaction mixture. Ammonium persulfate acted as an oxidizing agent, initiating the oxidative polymerization of aniline monomers to form PANi. Polymerization was visually confirmed by a color change from brown to dark green, indicating the transition from the oxidized aniline to the emeraldine salt form of PANi. This transformation occurred within minutes, signifying the successful synthesis of the polymer.

To achieve a thin and uniform PANi/phytic acid layer, the original reaction solutions containing aniline monomers and phytic acid were systematically diluted with deionized water to concentrations of 100, 200, 400, and 500 times their initial strength. This dilution strategy enabled precise control over the deposition of the polymeric material, allowing for the formation of thinner and more uniform layers on the Nano-TiO2 substrate. This approach not only reduced the thickness of the PANi/phytic acid film but also optimized the photoelectrochemical properties of the Nano-TiO2 electrode.

The resulting PANi/phytic acid complex formed a conformal and conductive thin coating on the Nano-TiO2 surface, as illustrated in Figure 1.

The -H2PO4 groups in phytic acid form hydrogen bonds with hydroxyl groups on the Nano-TiO2 surface, thereby enhancing interfacial adhesion between PANi and Nano-TiO2. This improved bonding strengthens the mechanical integrity of the composite and increases its cycling stability. Additionally, phytic acid acts as a cross-linker during aniline polymerization, facilitating interchain connections among PANi chains and resulting in a conformal, uniform conductive layer. This structure enhances electron transport and supports morphological stability. Furthermore, due to its doping ability, phytic acid induces a positive charge on PANi, enabling electrostatic interaction with the negatively charged Nano-TiO2 surface.

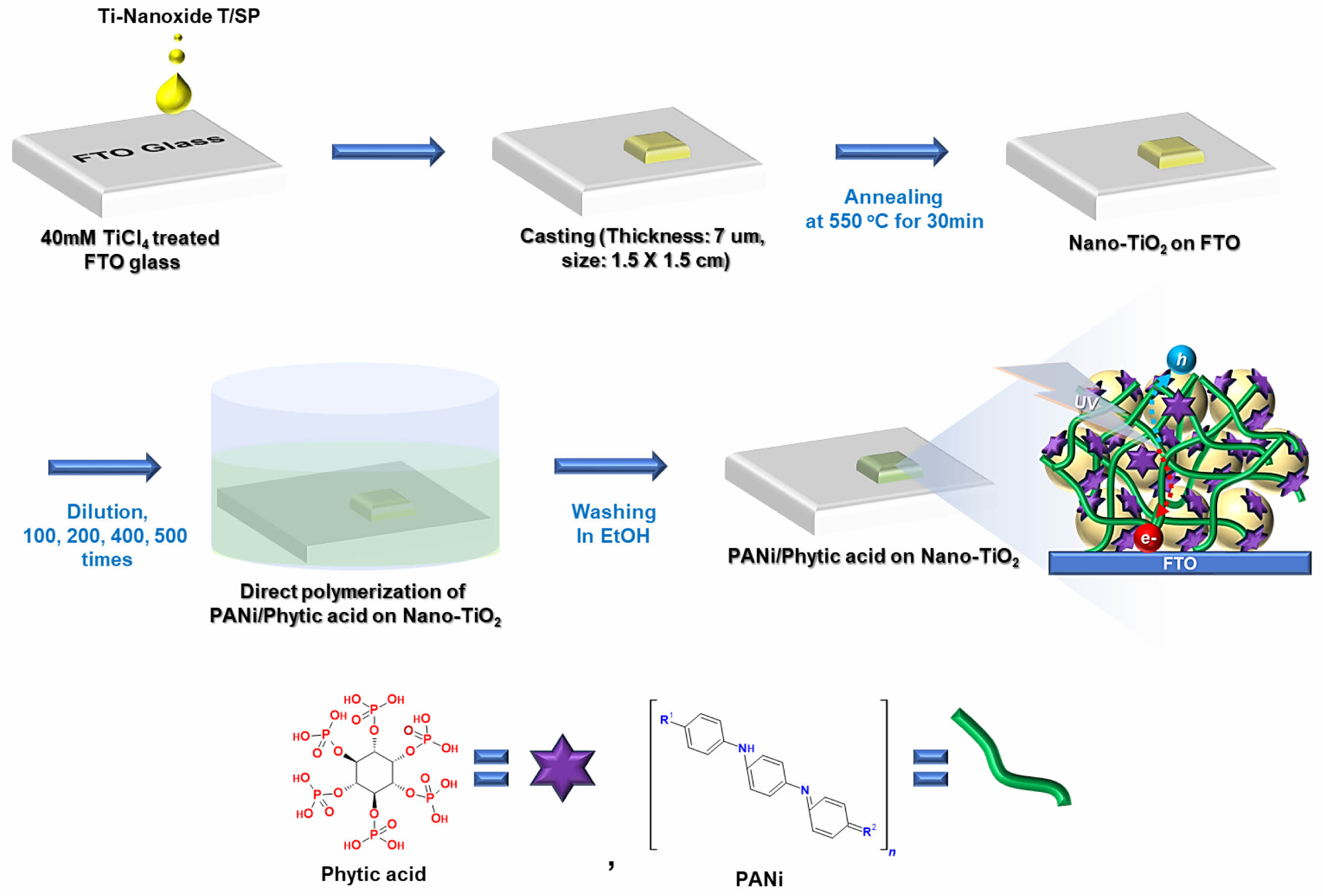

FE-SEM and FE-TEM analyses were performed to evaluate the surface morphology and adhesion of the PANi/phytic acid layer on TiO2-coated FTO glass substrates. As depicted in Figure 2(a), the PANi/phytic acid coating exhibited a uniform, crack-free morphology, indicating strong adhesion to the underlying TiO2 film. Figures 2(c) and (d) present the FE-TEM images of the synthesized TiO2 material, which reveal the formation of well-defined nanoparticles. FE-TEM, a highly advanced characterization technique, provides precise in-sights into the surface features of nanomaterials, including their shape, structural arrangement, and particle size distribution. The analysis confirmed the uniform morphology and nanoscale dimensions of the TiO2 particles, with an average size of approximately 50 nm, highlighting their critical role in influencing photocatalytic and electronic properties.

FE-SEM and FE-TEM analyses were performed to evaluate the surface morphology and adhesion of the PANi/phytic acid layer on TiO2-coated FTO glass substrates.

As depicted in Figure 2(a), the PANi/phytic acid coating exhibited a uniform, crack-free morphology, indicating strong adhesion to the underlying TiO2 film. Figures 2(c) and (d) present the FE-TEM images of the synthesized TiO2 material, which reveal the formation of well-defined nanoparticles. FE-TEM, a highly advanced characterization technique, provides precise insights into the surface features of nanomaterials, including their shape, structural arrangement, and particle size distribution. The analysis confirmed the uniform morphology and nanoscale dimensions of the TiO2 particles, with an average size of approximately 50 nm, highlighting their critical role in influencing photocatalytic and electronic proper-ties.

By visualizing the material at the nanometer scale, FE-TEM enables a thorough under-standing of the structural and morphological characteristics of the TiO2 material, facilitating the establishment of correlations between these attributes and its functional performance in diverse applications. This homogeneity ensures the formation of a continuous conductive network, which is vital for achieving electrochemical stability and enhanced performance. The overall thickness of the TiO2 electrode, including the PANi/phytic acid layer, was measured to be approximately 7.6 µm, as shown in Figure 2(a). To confirm the successful synthesis and distribution of PANi within the Nano-TiO2 electrode, SEM-EDXA mapping was performed in the region marked with a red cross in Figure 2(a). Mapping analysis revealed a substantial presence of nitrogen (N) elements in the innermost regions of the TiO2 matrix, as shown in Figure 2(b). The detection of nitrogen, a key element in PANi, confirmed that aniline monomers effectively infiltrated the porous structure of Nano-TiO2 during the immersion process. The subsequent oxidative polymerization resulted in a uniform PANi layer distributed throughout the TiO2 electrode. The uniform penetration and polymerization of PANi within the TiO2 matrix validated the synthesis procedure, confirming the creation of a robust electrode with enhanced electrochemical properties suitable for a range of applications.29

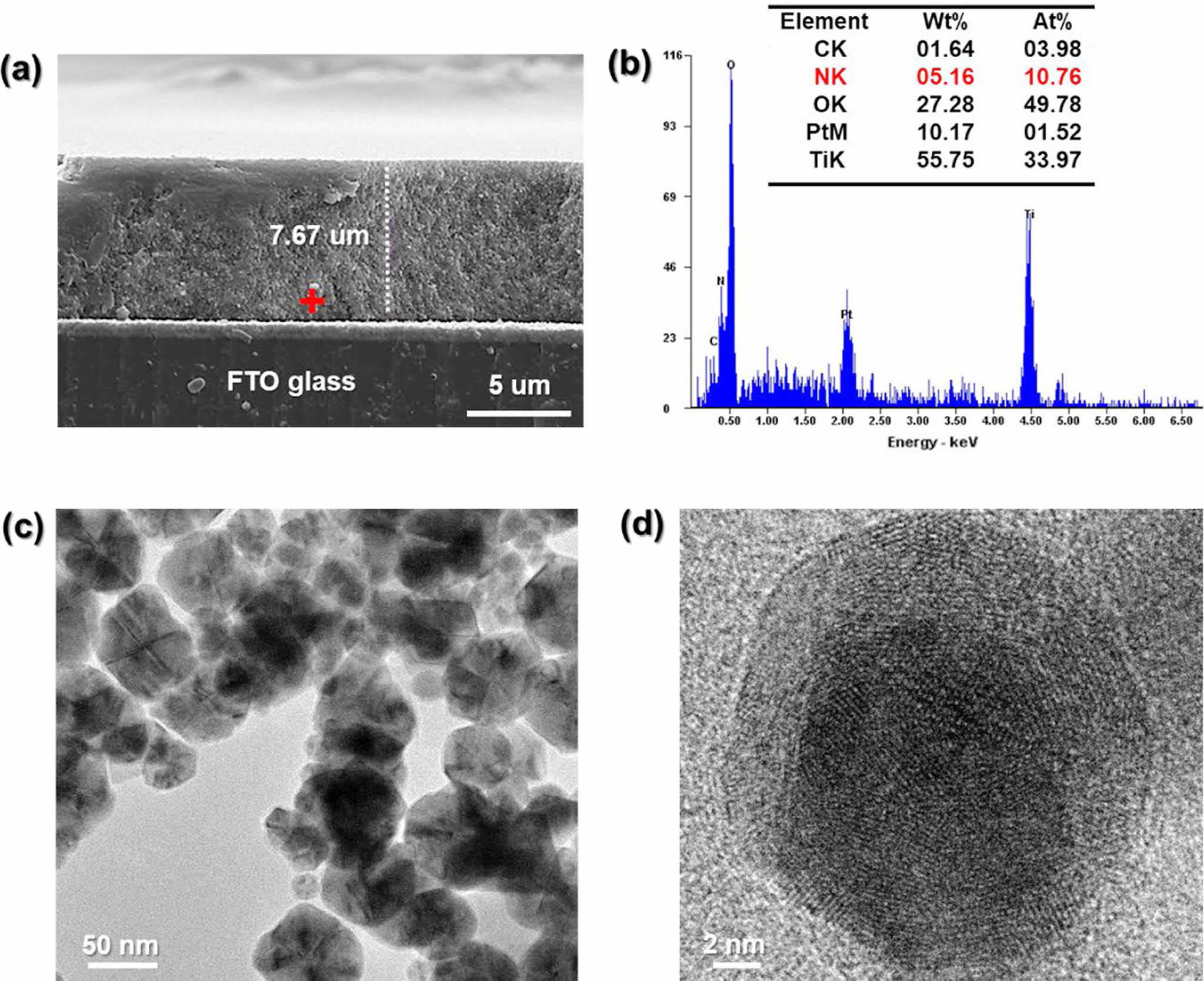

A representative XRD pattern of the TiO2 electrode deposited on an FTO glass substrate is shown in Figure 3(a) The XRD pattern features prominent diffraction peaks at 25.4° and 48.2°, corresponding to the (101) and (200) crystal planes of anatase TiO2, respectively (PDF Card No.: 01-073-1764). The anatase phase is widely regarded as the most photo-catalytically active form of TiO2, owing to its favorable electronic properties and high sur-face activity. The well-defined peaks in the XRD pattern confirm the successful formation of a pristine Nano-TiO2 electrode with a highly crystalline anatase structure. This structural integrity is essential to ensure the efficiency of the electrode in photocatalytic and photoelectrochemical processes.24,30 Figure 3(b) displays the BET analysis of Nano-TiO2, indicating a specific surface area of 43.5 m2/g. The interconnected porous network facilitates rapid diffusion of ions and molecules, improving the kinetics of electrochemical and photocatalytic processes. porous network reduces the charge carrier migration path length and supports efficient electron–hole separation, thereby minimizing recombination losses and enhancing charge transport. Nanostructured porosity enhances light scattering and absorption, particularly beneficial in photocatalysis and photo- electrochemical applications, where photon utilization is critical. The pore size, volume, and morphology can be precisely tailored to suit specific application needs, while also reducing material density without compromising mechanical integrity.

After the deposition of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2, the UV-vis spectra (Figure 3(c)) displayed minimal differences among the prepared TiO2 electrodes.31 This can be attributed to the effective deposition of a very small amount of PANi/phytic acid (2.6%), as demonstrated in Figure 3(d). These findings suggest that the PANi/phytic acid coating successfully enhanced the light absorption characteristics of the electrodes without significantly reducing the surface area of the nanoporous structure. A detailed depiction of the energy bandgap, derived from the light absorption properties, is provided in Figure 5.

Overall, these detailed analyses using FE-SEM, FE-TEM, SEM-EDXA, and XRD provide comprehensive evidence for the successful synthesis of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrodes with strong structural, morphological, and compositional integrity. These results highlighted the potential of these electrodes for advanced electrochemical and photocatalytic applications.

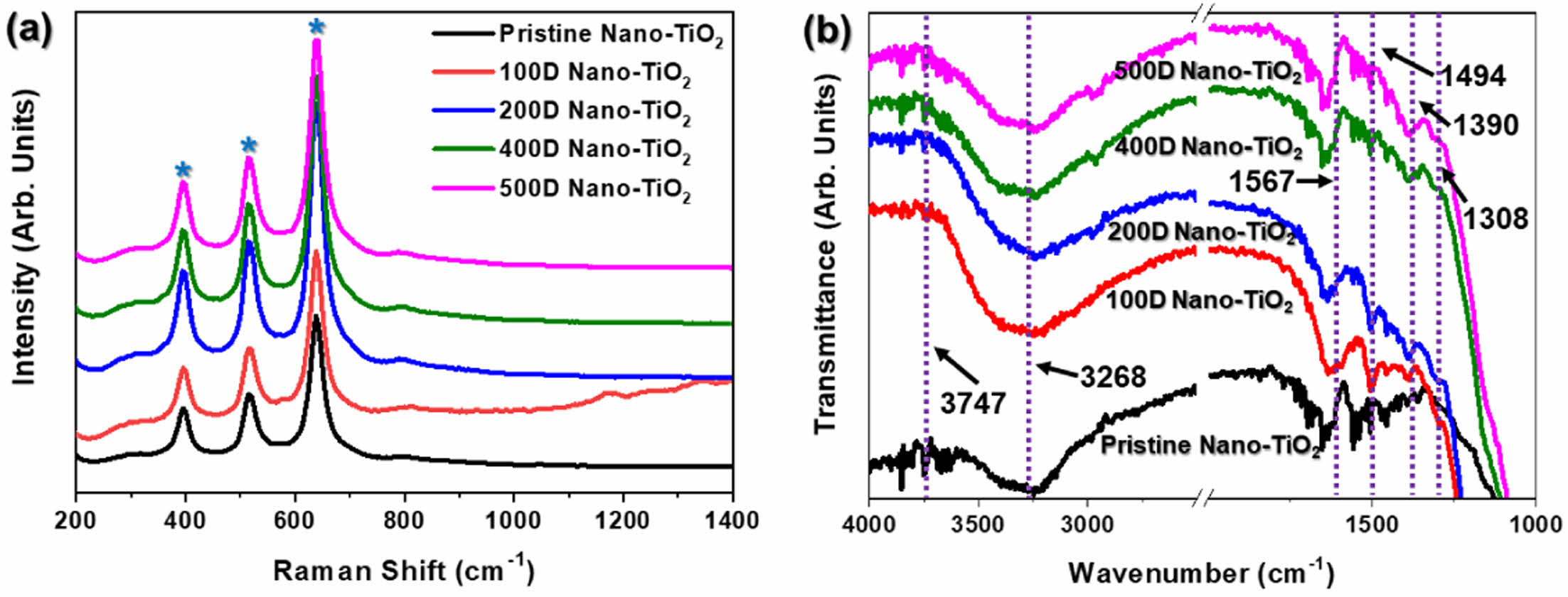

Raman spectroscopy is a critical analytical technique for identifying the crystalline phases of TiO2, and complements XRD in providing a detailed structural analysis. The Raman spectra of the samples, shown in Figure 4(a), exhibit distinct peaks that are characteristic of TiO2. Specifically, the peaks at 395 cm-1, 515 cm-1, and 638 cm-1, marked with blue stars, are attributed to the anatase phase of TiO2, confirming the presence of this highly photo-catalytically active phase in the samples.32,33 Notably, when the degree of dilution of the reaction solution increased, the Raman spectra in the TiO2 peaks remained largely un-changed, indicating that the PANi/phytic acid layer did not interfere with or alter the crystal structure of TiO2. However, the 100D sample displayed significant Raman signal scattering, which was attributed to the deposition of an excessively thick PANi/phytic acid layer on the TiO2 surface, potentially affecting the quality of the signal due to light scattering effects.

The FT-IR spectra (Figure 4(b)) provide further evidence of the presence of PANi in the Nano-TiO2 electrodes prepared using various diluted reaction solutions. TiO2 is identified by two characteristic absorbance peaks in the (OH) stretching region (3100–4000 cm-1). The broad band at 3260 cm-1 corresponds to weakly bonded hydroxyl groups, whereas the peak at 3747 cm-1 is associated with non-hydrogen-bonded hydroxyl groups, both of which are intrinsic features of the TiO2 surface. The PANi layer is clearly evidenced by specific absorbance peaks, including the band at 1308 cm-1, which is a distinct marker for C-N stretching, a characteristic vibration of PANi. Additionally, the peaks observed at 1567 cm-1 and 1390 cm-1 correspond to the stretching vibrations of the quinoid and benzenoid rings, respectively, which are structural motifs of PANi. These spectral features confirmed that the PANi/phytic acid layer predominantly existed in the emeraldine form, which is the conductive and electrochemically active form of PANi, rather than in the fully reduced leucoemeraldine or fully oxidized pernigraniline forms.31,34,35

These results collectively confirm that the PANi/phytic acid layer was successfully polymerized and uniformly coated onto the TiO2 surface. Raman and FTIR analyses verified that the PANi/phytic acid layer adhered to the TiO2 electrode without altering its inherent crystalline properties. This finding highlights the stability of the PANi/phytic acid coating and its compatibility with the TiO2 electrode; the coating preserved the structural and functional integrity of the electrode while enhancing its photoelectrochemical properties.

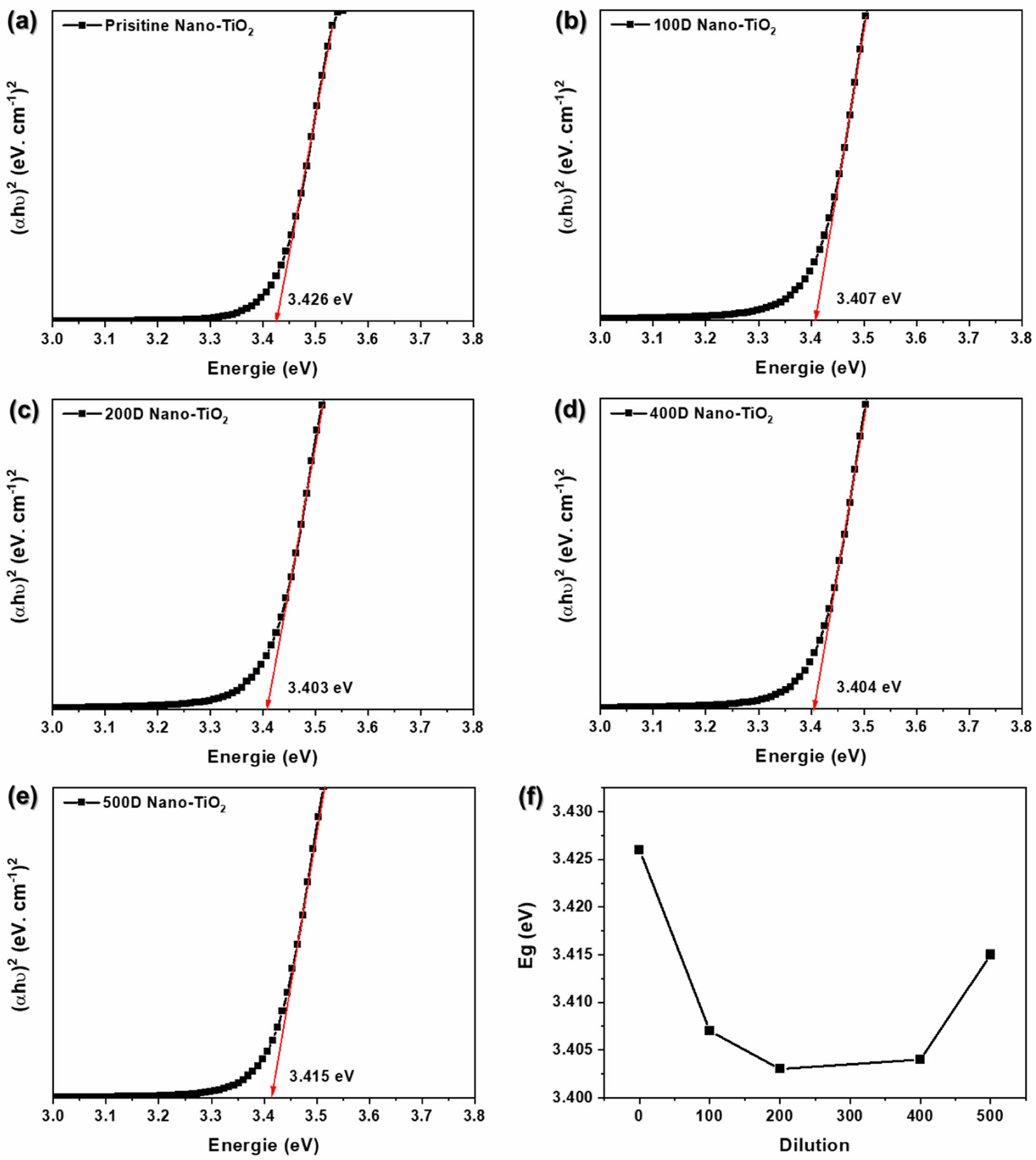

The optical properties have great importance in the study of photocatalytic materials because optical property represents the number of photons which will be absorbed during photocatalysis. Basically, the electronic structure and optical properties of prepared samples are analyzed by UV–vis spectroscopy. Tauc plot of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrode prepared using various diluted reaction solutions was shown in Figure 5(a)-(e). The higher absorbance in the high wavelength region between 300 and 400 nm is shown in Figure 3(c). The optical energy band of a semiconductor was obtained by using the following equation:

where k is a constant, α is the absorption coefficient, Eg is the energy band gap, and n is 1 for a direct energy band gap. The energy band gap can be estimated from Tauc plot between (αhυ)2 versus energy of photon (hυ).36 The intercept of the tangent on the Tauc plot gives a direct band gap for n=1. As shown in Figure 5, the pristine Nano-TiO2 exhibited the band gap at 3.426 eV. The band gap of TiO2 was significantly decreased after surface treatment with PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2. The 200D Nano-TiO2 electrodes likely achieved an optimal balance (3.403 eV) in PANi/phytic acid deposition, providing sufficient coverage to enhance optical absorption through the π-conjugated polymer network while maintaining a layer thickness that allowed effective light penetration to the nano-TiO2 surface. This balance facilitated improved photocatalytic activity by enabling efficient light harvesting and charge transfer.

In contrast, the 500D nano-TiO2 electrodes exhibited relatively insufficient PANi/phytic acid coverage. The reduced polymer deposition resulted in suboptimal light absorption, as the π-conjugated polymer layer was insufficient to capture and utilize photons effectively. Consequently, the limited optical absorption capacity hindered the overall photocatalytic performance, emphasizing the importance of precise control over the deposition process to achieve the desired functional properties.

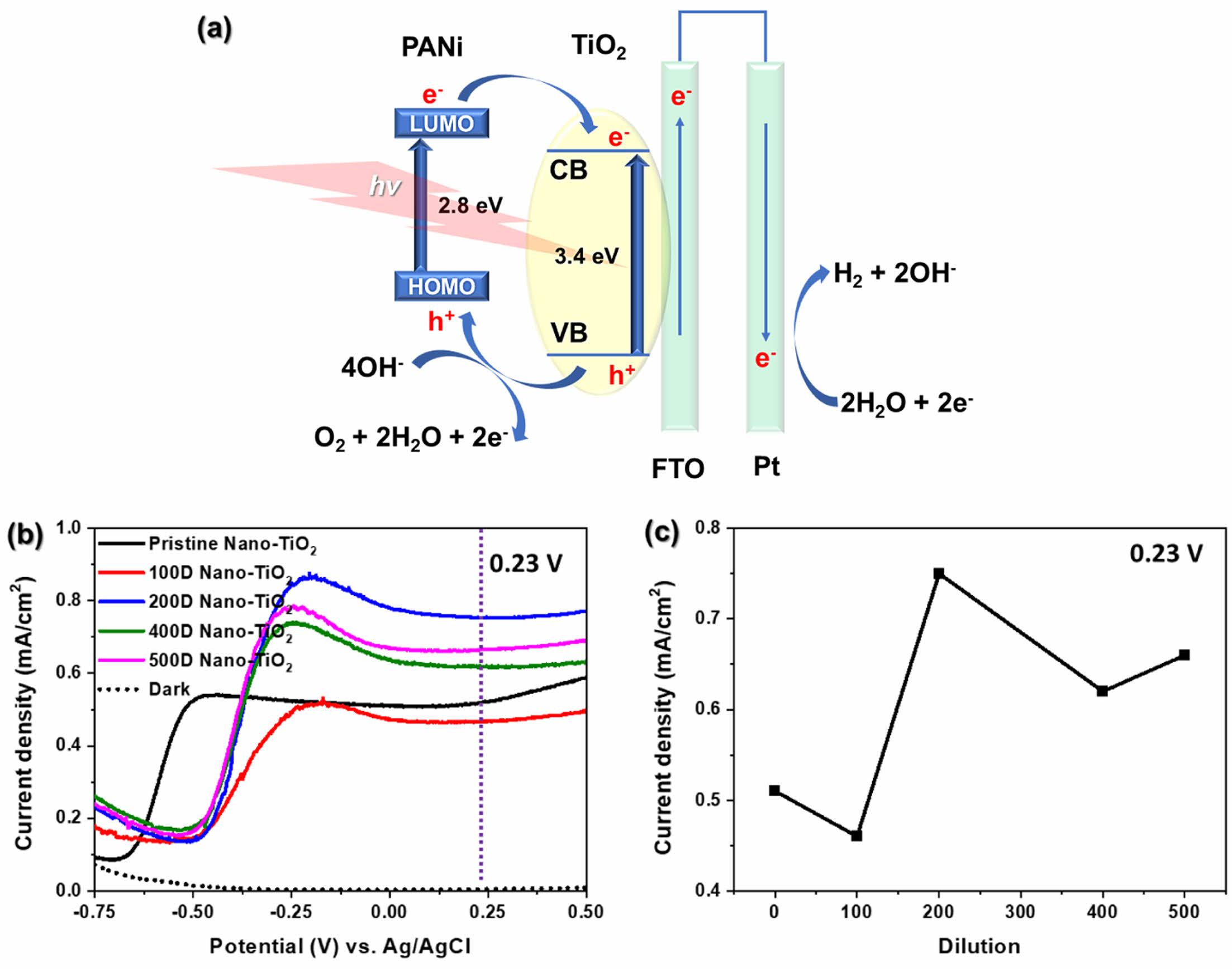

Figure 6(a) illustrates the processes of photoexcitation, charge separation, and subsequent reactions in the PANi/nano-TiO2 system under light illumination. In the emeraldine form, the HOMO of PANi corresponds to the polaron band, while its LUMO aligns with the π* band. Upon UV-vis irradiation, PANi absorbs photons, resulting in the excitation of electrons from its HOMO to its LUMO. Simultaneously, TiO2 absorbs UV photons, promoting electrons from its valence band (VB) to its conduction band (CB), leaving behind holes in the VB capable of oxidizing water (OH- in basic media) to O2.

The energy alignment between PANi and Nano-TiO2 plays a crucial role in efficient charge transfer. Electrons excited to the LUMO of PANi are injected into the CB of TiO2, promoting effective charge carrier separation and enhancing electron mobility.

Furthermore, electrostatic interactions between the negatively charged Nano-TiO2 surface and the positively charged, phytic acid-doped PANi contribute to the formation of a continuous conductive network, enhancing the mobility of charge carriers. These electrons are subsequently transferred to the FTO substrate and directed toward the cathode, where they participate in H2 evolution. Concurrently, the holes generated in the VB of TiO2 migrate to its surface, where they oxidize OH- ions to produce O2. This synergistic interaction between PANi and TiO2 facilitates enhanced photoelectrochemical performance.

The PEC performance of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrodes was evaluated for water photoelectrolysis in a 0.1 M NaOH solution. As shown in Figure 6(b), the pristine TiO2 electrode demonstrated a notable increase in current density—starting at approximately -0.65 V vs. Ag/AgCl and reaching 0.51 mA/cm2 at 0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl, corresponding to the saturation point of the TiO2 semiconductor. In contrast, the 100D, 200D, 400D, and 500D Nano-TiO2 electrodes exhibited a pronounced increase in current density, starting at approximately 0.48 V vs. Ag/AgCl. At 0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl, the current densities for these electrodes were 0.51, 0.46, 0.75, 0.62, and 0.66 mA/cm2, respectively (Figure 6c). The enhanced performance of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrodes compared to that of pristine Nano-TiO2 is primarily attributed to the improved photocatalytic and charge transport properties. This enhancement results from the conductive network formed by PANi, which facilitates more efficient charge transport and reduces electron-hole recombination, which is a critical factor in photocatalytic processes. Additionally, phytic acid contributed to stabilizing the PANi layer on the Nano-TiO2 surface by providing robust adhesion and maintaining structural integrity. The synergistic effects of PANi and phytic acid further enabled efficient electron transfer and improved photocatalytic activity, enhancing the overall effectiveness of the system for photoelectrochemical applications. Among the prepared electrodes, the 200D Nano-TiO2 exhibited the highest current density at 0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl (Figures 6(b) and 6(c)). The 200D Nano-TiO2 likely achieved a balance between sufficient deposition of PANi/phytic acid necessary to create an effective conductive network while also avoiding excessive layer thickness that could impede light penetration. In contrast, the 100D Nano-TiO2 electrode, which had an excessively thick PANi/phytic acid layer, suffered from reduced light absorption and lower photocatalytic activity owing to the blocking of the active sites on the TiO2 surface. However, the 400D and 500D Nano-TiO2 electrodes had relatively insufficient PANi/phytic acid coverage, which prevented the formation of the continuous conductive network necessary for efficient charge transport and photocatalytic performance. These findings highlight the importance of optimizing PANi/phytic acid coverage to maximize the PEC performance of TiO2-based electrodes.

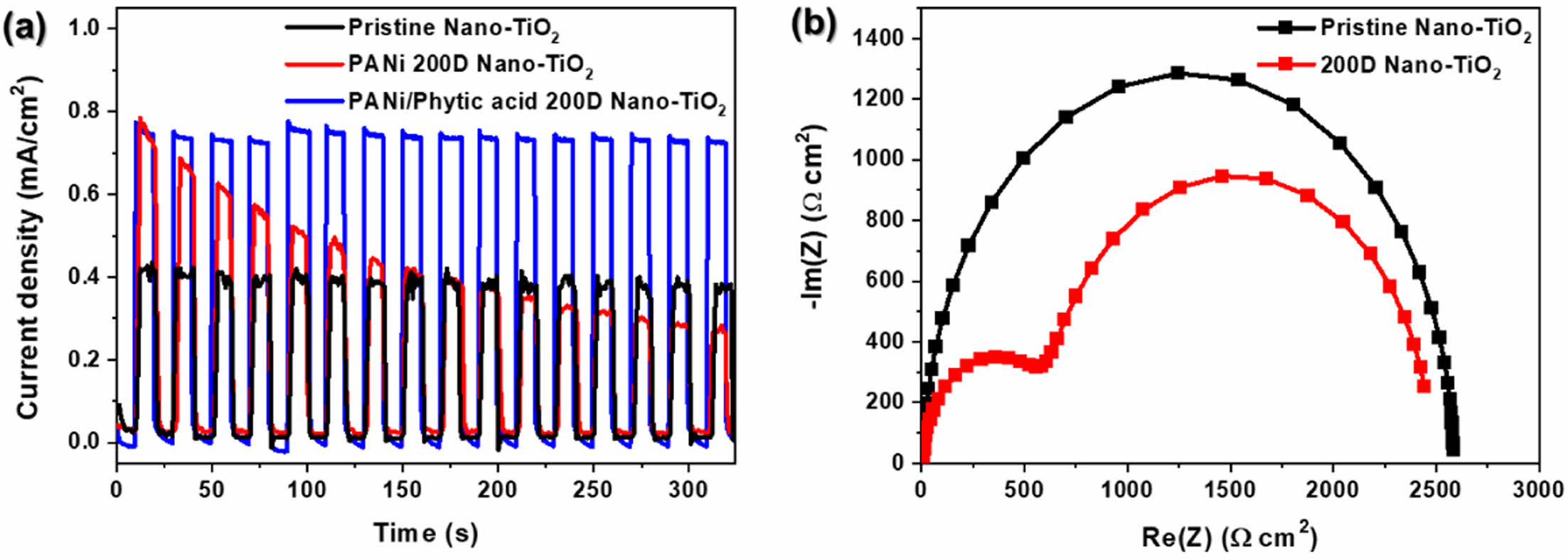

To evaluate the long-term stability of the photoelectrodes, chronoamperometric I-t curves were recorded for pristine Nano-TiO2, PANi 200D Nano-TiO2, and PANi/phytic acid 200D Nano-TiO2 at 0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl under chopped illumination (AM 1.5G, 100 mW/cm2) in a 1 M NaOH solution. The light/dark cycles were alternated every 10 s for a total duration of 320 s (Figure 6(a)). Initially, both PANi 200D Nano-TiO2 and PANi/phytic acid 200D Nano-TiO2 demonstrated current densities 1.4 times higher than that of pristine Nano-TiO2, indicating their enhanced photocatalytic performance. However, as the cycling progressed, the current density of PANi 200D Nano-TiO2 decreased significantly, suggesting instability in its performance. In contrast, PANi/phytic acid 200D Nano-TiO2 exhibited a stable current density throughout the cycling, highlighting its superior durability. This stability is attributed to the -H2PO4 groups in phytic acid, which enhance the bonding stability between Nano-TiO2 and the PANi layer, thereby maintaining efficient electron-transfer properties and structural integrity during extended operation.

To further investigate the charge transport properties, EIS was conducted on the pristine Nano-TiO2 and 200D Nano-TiO2 electrodes in 1 M NaOH electrolyte under open-circuit voltage conditions. The Nyquist plots (Figure 6(b)) reveal that the semicircle diameter in the middle-frequency region, which represents the interfacial charge-transfer resistance, was significantly smaller for 200D Nano-TiO2 than for pristine Nano-TiO2.

This reduced resistance indicates improved contact and lower interfacial resistance, which enhanced the intrinsic conductivity of 200D Nano-TiO2. This improved charge transport facilitated efficient electron transfer between the electrode and electrolyte, suppressing charge carrier recombination and improving the overall photoelectrochemical performance. These findings emphasize the effectiveness of PANi/phytic acid in enhancing the stability and charge transfer capabilities of TiO2-based photoelectrodes. Fig. 7

|

Figure 1 Schematic illustration for thin layer of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrode. |

|

Figure 2 (a) FE-SEM image of cross-section; (b) SEM-EDXA analysis for PANi/phytic acid on nano-TiO2, for PANi/phytic acid on nanoTiO2; (c) and (d) FE-TEM images for pristine Nano-TiO2. |

|

Figure 3 (a) XRD pattern; (b) BET analysis for TiO2 electrode; (c) UV-vis spectra for PANi/phytic acid on nano-TiO2; (d) thermal gravimetric analysis (TGA) of pristine and 200D Nano-TiO2. |

|

Figure 4 (a) Raman and (b) FTIR spectra of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrode prepared using various diluted reaction solutions. |

|

Figure 5 (a) Pristine; (b) 100D; (c) 200D; (d) 400D; (e) 500D for Tauc plot of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrode; (f) Eg according to various diluted reaction solutions. |

|

Figure 6 EC characterization of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrodes prepared using various di-luted reaction solutions: (a) reaction route of UV-vis light absorption and charge transfer in PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 for photoelectrochemical water splitting; (b) I-V curves recorded at a scan rate of 10 mV/s under illumination (AM 1.5G, 100 mW/cm2); (c) current density at 0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl. |

|

Figure 7 (a) I-t curve recorded at 0.23 V vs. Ag/AgCl under illumination with alternating 10 s light and dark cycles for pristine nano-TiO2, PANi and PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 prepared under optimal dilution; (b) nyquist plots of pristine and 200D Nano-TiO2 at open circuit potential un-der illumination. |

This study demonstrated the successful synthesis and integration of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 surfaces to enhance their photocatalytic performance in water-splitting applications. The incorporation of phytic acid significantly improved the bonding stability between PANi and Nano-TiO2, maintaining structural integrity and efficient electron transfer over extended cycles. PANi contributed to enhanced charge transport, whereas the -H2PO4 groups in phytic acid facilitated robust adhesion, jointly enabling the formation of a stable and conformal conductive network on the Nano-TiO2 surface.

Among the prepared electrodes, the 200D Nano-TiO2 electrode exhibited the highest photocurrent density and superior cycling stability, which were attributed to its optimal PANi/phytic acid coverage. EIS further revealed a reduced interfacial charge transfer resistance in the 200D Nano-TiO2 electrode, underscoring its improved intrinsic conductivity and suppressed charge-carrier recombination.

These findings highlight the synergistic effects of PANi and phytic acid in addressing the intrinsic limitations of TiO2, including limited rapid electron-hole recombination. Hence, the proposed use of PANi/phytic acid on Nano-TiO2 electrodes is a promising approach for developing high-performance, eco-friendly photocatalytic systems, thereby contributing to sustainable hydrogen production and advancing renewable energy technologies.

- 1. Tijjani Usman, I. M.; Ho, Y.-C.; Baloo, L.; Lam, M.-K.; Sujarwo, W. A Comprehensive Review on the Advances of Bioproducts from Biomass Towards Meeting Net Zero Carbon Emissions (NZCE). Bioresour. Technol. 2022, 366, 128167.

-

- 2. Srivastava, R. K.; Shetti, N. P.; Reddy, K. R.; Kwon, E. E.; Nadagouda, M. N.; Aminabhavi, T. M. Biomass Utilization and Production of Biofuels from Carbon Neutral Materials. Environ. Pollut. 2021, 276, 116731.

-

- 3. Antar, M.; Lyu, D.; Nazari, M.; Shah, A.; Zhou, X.; Smith, D. L. Biomass for a Sustainable Bioeconomy: An Overview of World Biomass Production and Utilization. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2021, 139, 110691.

-

- 4. Richardson, Y.; Blin, J.; Julbe, A. A Short Overview on Purification and Conditioning of Syngas Produced by Biomass Gasification: Catalytic Strategies, Process Intensification and New Concepts. Prog. Energy Combust. Sci. 2012, 38, 765-781.

-

- 5. Apostu, S. A.; Nichita, E. M.; Manea, C. L.; Irimescu, A. M.; Vulpoi, M. Exploring the Influence of Innovation and Technology on Climate Change. Energies 2023, 16, 6408.

-

- 6. He, M.; Sun, Y.; Han, B. Green Carbon Science: Efficient Carbon Resource Processing, Utilization, and Recycling Towards Carbon Neutrality. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2022, 61, e202112835.

-

- 7. Corma, A. Preface to Special Issue of ChemSusChem on Green Carbon Science: CO2 Capture and Conversion. ChemSusChem 2020, 13, 6054-6055.

-

- 8. He, M.; Sun, Y.; Han, B. Green Carbon Science: Scientific Basis for Integrating Carbon Resource Processing, Utilization, and Recycling. Angew. Chem. Int. Ed. 2013, 52, 9620-9633.

-

- 9. Dincer, I. Renewable Energy and Sustainable Development: a Crucial Review. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2000, 4, 157-175.

- 10. Yue, M.; Lambert, H.; Pahon, E.; Roche, R.; Jemei, S.; Hissel, D. Hydrogen Energy Systems: A Critical Review of Technologies, Applications, Trends and Challenges. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2021, 146, 111180.

-

- 11. Winter, C.-J. Hydrogen Energy—Abundant, Efficient, Clean: A Debate Over the Energy-system-of-change. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2009, 34, S1-S52.

-

- 12. Midilli, A.; Kucuk, H.; Topal, M. E.; Akbulut, U.; Dincer, I. A Comprehensive Review on Hydrogen Production From Coal Gasification: Challenges and Opportunities. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2021, 46, 25385-25412.

-

- 13. Stiegel, G. J.; Ramezan, M. Hydrogen from Coal Gasification: An Economical Pathway to a Sustainable Energy Future. Int. J. Coal Geol. 2006, 65, 173-190.

-

- 14. Chi, J.; Yu, H. Water Electrolysis Based on Renewable Energy for Hydrogen Production. Chin. J. Catal. 2018, 39, 390-394.

- 15. Burton, N. A.; Padilla, R. V.; Rose, A.; Habibullah, H. Increasing the Efficiency of Hydrogen Production from Solar Powered Water Electrolysis. Renew. Sust. Energ. Rev. 2021, 135, 110255.

-

- 16. Smolinka, T. FUELS – HYDROGEN PRODUCTION | Water Electrolysis. In Encyclopedia of Electrochemical Power Sources, Garche, J. Ed.; Elsevier: Amsterdam, 2009; pp 394-413.

-

- 17. Mohamed Jan, B.; Bin Dahari, M.; Abro, M.; Ikram, R. Exploration of Waste-generated Nanocomposites as Energy-driven Systems for Various Methods of Hydrogen Production; A Review. Int. J. Hydrog. Energy 2022, 47, 16398-16423.

-

- 18. Fujishima, A.; Honda, K. Electrochemical Photolysis of Water at a Semiconductor Electrode. Nature 1972, 238, 37-38.

-

- 19. Moridon, S. N. F.; Arifin, K.; Yunus, R. M.; Minggu, L. J.; Kassim, M. B. Photocatalytic Water Splitting Performance of TiO2 Sensitized by Metal Chalcogenides: A Review. Ceram. Int. 2022, 48, 5892-5907.

-

- 20. Preethi, L. K.; Mathews, T.; Nand, M.; Jha, S. N.; Gopinath, C. S.; Dash, S. Band Alignment and Charge Transfer Pathway in Three Phase Anatase-rutile-brookite TiO2 Nanotubes: An Efficient Photocatalyst for Water Splitting. Appl. Catal. B: Environ. 2017, 218, 9-19.

-

- 21. Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Ling, Y.; Tang, Y.; Yang, X.; Fitzmorris, R. C.; Wang, C.; Zhang, J. Z.; Li, Y. Hydrogen-Treated TiO2 Nanowire Arrays for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. Nano Lett. 2011, 11, 3026-3033.

-

- 22. Li, Y.; Peng, Y.-K.; Hu, L.; Zheng, J.; Prabhakaran, D.; Wu, S.; Puchtler, T. J.; Li, M.; Wong, K.-Y.; Taylor, R. A.; Chi, S.; Tsang, E. Photocatalytic Water Splitting by N-TiO2 on MgO (111) With Exceptional Quantum Efficiencies at Elevated Temperatures. Nat. Commun. 2019, 10, 4421.

-

- 23. Jung, J. W.; Lee, J. U.; Jo, W. H. High-Efficiency Polymer Solar Cells with Water-Soluble and Self-Doped Conducting Polyaniline Graft Copolymer as Hole Transport Layer. J. Phys. Chem. C 2010, 114, 633-637.

-

- 24. Hidalgo, D.; Bocchini, S.; Fontana, M.; Saracco, G.; Hernández, S. Green and Low-cost Synthesis of PANI–TiO2 Nanocomposite Mesoporous Films for Photoelectrochemical Water Splitting. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 49429-49438.

-

- 25. Pan, L.; Yu, G.; Zhai, D.; Lee, H. R.; Zhao, W.; Liu, N.; Wang, H.; Tee, B. C.-K.; Shi, Y.; Cui, Y.; Bao, Z. Hierarchical Nanostructured Conducting Polymer Hydrogel with High Electrochemical Activity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. 2012, 109, 9287-9292.

-

- 26. Wu, H.; Yu, G.; Pan, L.; Liu, N.; McDowell, M. T.; Bao, Z.; Cui, Y. Stable Li-ion Battery Anodes by In Situ Polymerization of Conducting Hydrogel to Conformally Coat Silicon Nanoparticles. Nat. Commun. 2013, 4, 1943.

-

- 27. Kim, J.-K.; Shin, K.-H.; Lee, K.-S.; Park, J.-H. Influence of a TiCl4 Treatment Condition on Dye-Sensitized Solar Cells. J. Electrochem. Sci. Technol. 2010, 1, 81-84.

- 28. Lee, S.-W. The Effect of TiOx Blocking Layer on the Performance of Dye-Sensitized Titanium Dioxide Solar Cells. Mol. Cryst. Liquid Cryst. 2011, 551, 172-180.

-

- 29. Molina, J.; Esteves, M. F.; Fernández, J.; Bonastre, J.; Cases, F. Polyaniline Coated Conducting Fabrics. Chemical and Electrochemical Characterization. Eur. Polym. J. 2011, 47, 2003-2015.

-

- 30. Jing, L.; Yang, Z.-Y.; Zhao, Y.-F.; Zhang, Y.-X.; Guo, X.; Yan, Y.-M.; Sun, K.-N. Ternary Polyaniline–graphene–TiO2 Hybrid with Enhanced Activity for Visible-light Photo-electrocatalytic Water Oxidation. J. Mater. Chem. A 2014, 2, 1068-1075.

-

- 31. Li, X.; Wang, D.; Luo, Q.; An, J.; Wang, Y.; Cheng, G. Surface Modification of Titanium Dioxide Nanoparticles by Polyaniline via An In Situ Method. J. Chem. Technol. Biotechnol. 2008, 83, 1558-1564.

-

- 32. Ilie, A. G.; Scarisoareanu, M.; Morjan, I.; Dutu, E.; Badiceanu, M.; Mihailescu, I. Principal Component Analysis of Raman Spectra for TiO2 Nanoparticle Characterization. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2017, 417, 93-103.

-

- 33. Ohsaka, T.; Izumi, F.; Fujiki, Y. Raman Spectrum of Anatase, TiO2. J. Raman Spectrosc. 1978, 7, 321-324.

-

- 34. Li, X.; Chen, W.; Bian, C.; He, J.; Xu, N.; Xue, G. Surface Modification of TiO2 Nanoparticles by Polyaniline. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2003, 217, 16-22.

-

- 35. Pawar, S. G.; Patil, S. L.; Chougule, M. A.; Mane, A. T.; Jundale, D. M.; Patil, V. B. Synthesis and Characterization of Polyaniline:TiO2 Nanocomposites. Int. J. Polym. Mater. Polym. Biomat. 2010, 59, 777-785.

-

- 36. Wang, Y.; Herron, N. Nanometer-sized Semiconductor Clusters: Materials Synthesis, Quantum Size Effects, and Photophysical Properties. J. Phys. Chem. 1991, 95, 525-532.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(6): 757-768

Published online Nov 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.6.757

- Received on May 2, 2025

- Revised on Jun 12, 2025

- Accepted on Jul 27, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Jung-Soo Lee

-

Department of Bio-chemical Engineering, Chosun University, Chosundaegil 146, Dong-gu, Gwangju 61452, Korea

- E-mail: jslee15@chosun.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0002-3999-3180

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.