- Study on Functional Soft Contact Lenses with Blue Light Reducing Capability

Junseok Lee

, Dae Gyu Song*, Hong Jin Choi†

, Dae Gyu Song*, Hong Jin Choi†  and Jeong Koo Kim†

and Jeong Koo Kim†

Department of Biomedical Engineering, Inje University, Gimhae, Gyeongnam 50834, Korea

*Industry-Academic Cooperation Foundation, Inje University, Gimhae, Gyeongnam 50834, Korea- 청색광 감소 기능성 소프트 콘택트렌즈에 관한 연구

인제대학교 의공학과, *인제대학교 산학협력단

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

This study developed a functional soft contact lens capable of reducing blue light by incorporating beta-carotene, a natural antioxidant known for blue light absorption. Soft lens films were fabricated using a 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) polymer with various beta-carotene concentrations, and their optical, physical, and biological properties were evaluated. The beta-carotene-incorporated lenses effectively reduced blue light transmission while maintaining transparency and mechanical integrity up to 500 μM of beta-carotene. Hydrophilicity of the lenses slightly decreased at higher beta-carotene content, but beta-carotene release into solution was minimal. No cytotoxic effects were observed in cell viability tests; in fact, higher beta-carotene concentrations showed enhanced cell proliferation, likely due to antioxidant effects. These results demonstrate that beta-carotene functionalized soft contact lenses can mitigate blue light exposure without compromising lens performance, though further work is needed to improve lens hydrophilicity for wearer comfort.

본 연구에서는 청색광 흡수와 항산화 기능을 가진 천연물질 베타카로틴을 소프트 콘택트렌즈에 첨가하여 청색광을 저감시키는 기능성 렌즈를 개발하였다. 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) 기반 폴리머에 다양한 농도의 베타카로틴을 첨가하여 제작한 렌즈 필름의 광학 및 물리적 특성을 평가한 결과, 베타카로틴 함유 렌즈는 투명도를 유지한 채 청색광 투과를 효과적으로 감소시켰으며 렌즈의 기계적 성질에도 유의한 변화가 없었다. 다만 베타카로틴 함량이 증가할수록 표면 친수성은 다소 감소했으나, 렌즈로부터의 베타카로틴 용출은 검출 한계 수준으로 매우 낮았으며, 세포 독성 역시 관찰되지 않았다. 이러한 결과를 통해 베타카로틴 함유 기능성 소프트 콘택트렌즈는 청색광 감소용으로 유망하며, 향후 친수성 개선을 통해 착용 적합성을 높일 필요가 있다.

A 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA)-based soft contact lens doped with the natural chromophore ¥â-carotene effectively attenuates blue light while maintaining optical transparency and mechanical integrity at loadings up to 500 ¥ìM. ¥â-Carotene release was minimal, and no cytotoxicity was observed, although surface hydrophilicity decreased modestly at higher loadings. These results highlight a polymer-centric approach to blue-light mitigation in ophthalmic devices.

Keywords: blue light, soft contact lens, beta-carotene, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate, antioxidant.

This research was supported by Ministry of Trade, Industry and Energy of Korea (RS-2024-00433095).

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

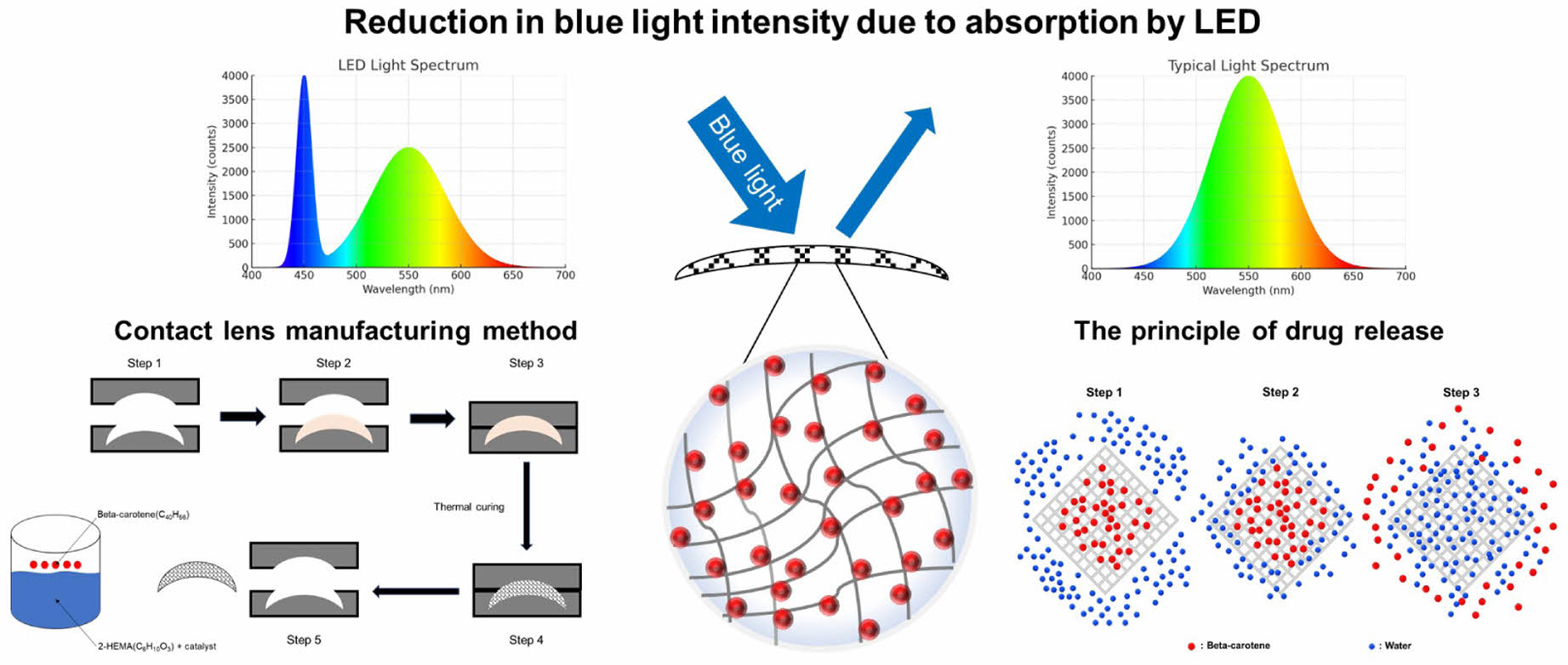

With the rapid advancement of digital display devices, modern individuals are increasingly exposed to artificial light sources from light emitting diode (LED) screens such as smartphones, monitors, and TVs.1 Artificial light sources can be broadly categorized into LED and lamp types, with most current display devices using LEDs.2 LED-based devices emit a significant amount of radiant intensity in the blue light spectrum, which falls within the visible light range.3 Studies have shown that while the radiant intensity of lamp types is similar to that of natural light (sunlight), the radiant intensity of LED types is more than twice as high compared to natural light.4 The blue light spectrum is known to range from approximately 350 nm to 500 nm in wavelength.5 This range also includes part of the ultraviolet (UV-A region) spectrum, leading blue light to be referred to as high-energy visible light (HEV).6

Commercial white LEDs are typically realized by exciting a yellow-emitting phosphor with a blue LED pump; the resulting spectra often contain a pronounced blue component that motivates blue-light filtering at the eye.7

Prolonged exposure to blue light can cause various health issues.8,9 For instance, excessive exposure to blue light can reach the retina and damage photoreceptor cells, leading to macular degeneration, sleep disorders, and vision deterioration.8 According to one study, lipofuscin, a pigment in the eye, can induce cell death when excessively exposed to blue light.8 Moreover, one of the representative diseases caused by blue light exposure is macular degeneration.10 The macula, located at the center of the retina, is crucial for sharp and detailed vision.11 Macular degeneration, exacerbated by blue light exposure, results in oxidative damage to retinal cells and is a leading cause of vision impairment and blindness, particularly in people over 40 years old.10,12 Additionally, blue light exposure can interfere with the production of melatonin, a hormone that regulates sleep, potentially causing sleep disorders.10

Contact lenses, as a vision correction medical device alternative to glasses, have seen increasing usage across various generations.13,14 Currently, over 60% of the population uses glasses or contact lenses, with approximately 20% opting for contact lenses.13,14 Contact lenses are broadly categorized into hard lenses and soft lenses, with over 90% of contact lens users choosing soft contact lenses.15 This growing demand for soft contact lenses is due to their comfort, wide field of vision, and reduced sensitivity to external environmental factors.15

2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA) is a principal monomer for soft contact lenses and is typically polymerized with a crosslinker such as EGDMA and initiated by AIBN or photoinitiators, often together with hydrophilic comonomers (e.g., methacrylic acid). 2-HEMA is a polar, hydrophilic monomer; its polymer (pHEMA) forms water-swollen hydrogels. A homopolymer pHEMA lens contains ~38 wt% water, and by adjusting comonomer content and crosslink density the equilibrium water content can be tuned to ~20–80 wt%.16

There are several methods to block blue light, including color change and physical coating. One approach involves using blue light-reducing materials to manufacture contact lenses. Coumarin and acridine are common blue light-blocking substances; however, they can pose toxicity risks when used in contact lenses that are in direct contact with the body.17 To address this issue, beta-carotene, a natural substance, has been selected for application in the eyes due to its safer profile. Beta-carotene is one of the important bioactive substances found in nature, primarily belonging to the carotenoid family.18 Carotenoids are organic pigments present as organic metabolic components in plants, algae, bacteria, and fungi, with more than 600 types of carotenoids discovered to date.18 The chemical structure of beta-carotene consists of two beta-ionone rings and a long conjugated double bond chain.19 This structure imparts strong antioxidant properties to beta-carotene.19 The conjugated double bond system stabilizes free radicals, preventing cellular damage.19 Additionally, this structure is highly effective in absorbing light, exhibiting strong absorbance in the wavelength range of 400 nm to 500 nm.20 Furthermore, beta-carotene can be converted into vitamin A (retinol) in the body, acting as an essential nutrient for maintaining vision, enhancing immune function, and supporting cell growth and differentiation.18

This study investigates beta-carotene–loaded 2‑HEMA films as blue‑light‑filtering contact lens materials that reduce the transmission of incident blue light (»400–500 nm) via spectral absorption while maintaining lens‑relevant properties. Beta-carotene has blue light-absorbing properties and antioxidant functions, providing a dual effect of reducing blue light exposure and protecting retinal cells from oxidative damage.

Materials. In this study, 2-hydroxyethyl methacrylate (2-HEMA, Junsei, JPN, Mw 130.14), ethylene glycol dimethacrylate (EGDMA, Sigma-Aldrich, USA, Mw 198.22), methacrylic acid (MA, Junsei, JPN, Mw 86.09), and a,a′-Azobis(isobutyronitrile) (AIBN, Junsei, JPN, Mw 164.21) were used to create a soft contact lens alternative film. During the polymerization process, 2-HEMA served as the main material, with EGDMA as the crosslinker, MA as the organic compound, and AIBN as the radical initiator. Custom-made silicone molds with areas of 10.56π and 2.25π were utilized for film production. Beta-carotene (Sigma-Aldrich, USA, Mw 536.87) was used for its blue light reduction and antioxidant properties. The cytotoxicity assessment was performed using CRL-4005 (Human skin fibroblast, ATCC, USA) cells. Human skin fibroblast cells were chosen because the skin and cornea share a common ectodermal embryonic origin, allowing for the study of stromal-epithelial interactions in specific situations such as wound healing.21 Due to these reasons, CRL-4005 cells were selected for the evaluation. The cells were cultured in a T-75 flask with Dulbecco’s Minimum Essential Medium (DMEM, Welgene, USA) supplemented with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS, Gibco, USA) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (P/S, Sigma-Aldrich, USA). Indirect toxicity was then assessed using the Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8, DOJINDO, Japan).

Equipment and Instrumentation. We measured spectral transmittance, T(λ), of the films by UV–Vis spectrophotometry (V-550, JASCO, TS Science, KOR) and calculated absorbance, A(λ) = −log10 T(λ). In addition, blue-band attenuation (%) at selected wavelengths (e.g., 425/475 nm) was computed as [1−T(λ)] × 100. We avoid the ambiguous term “absorption rate” and report A(λ) and attenuation (%) explicitly. To check the physical property changes based on the beta-carotene content, a Universal Testing Machine (LRX Plus, LLOYD, USA) was used. Hydrophilicity was evaluated with a contact angle analyzer (Phoenix 300 Touch, S.E.O. Co, Ltd, KOR). Drug release patterns over time were examined using a shaking incubator (SI-300R, Lab Companion, KOR). For cytotoxicity evaluation, samples were sterilized with an EO gas sterilizer (MK-EO30, MKT, KOR) and cytotoxicity was assessed with a Micro-plate Reader (iMARKTM, BIORAD, USA).

Fabrication Film for Soft Contact Lens Replacement by Polymerizing 2-HEMA. Soft contact lenses are typically cured in cylindrical/rotational molds and thus form semi-spherical parts that are unsuitable for standardized testing; therefore, flat films were cast as surrogates. The pre-cure (monomer) mixtures were fixed at 2-HEMA 99.2 wt%, EGDMA 0.4 wt% (crosslinker), MA 0.2 wt% (hydrophilic comonomer), and AIBN 0.2 wt% (thermal initiator) (all wt% relative to total monomers); only beta-carotene loading was varied (0–500 μM). Components were combined at room temperature and magnetically stirred for 60 min to homogeneity, then cast into a silicone mold (planform area 10.56π) and thermally cured at 110 ℃ for 40 min. After demolding, films were hydrated in PBS at room temperature for 24 h (lens-relevant condition). All processing conditions other than beta-carotene loading were kept identical across samples.

Note on residual monomers: A dedicated quantitative assay for residual (unreacted) monomers (e.g., ATR-FTIR residual vinyl quantification or solvent-extraction analysis) was not performed in this study. Nevertheless, within our test window, the films maintained macroscopic transparency and monotonic blue-band attenuation at lens-relevant thickness, and no cytotoxicity was observed, which indirectly supports sufficient conversion for the present proof-of-concept. A formal residual-monomer quantification is proposed for future work.

Fabrication of 2-HEMA Polymer Film Containing Beta-carotene and Analysis of Absorbance Distribution/absorption Rate. (1) Fabrication of 2-HEMA Polymer Film Containing Beta-Carotene: Because beta-carotene is strongly hydrophobic whereas 2-HEMA is polar/hydrophilic, beta-carotene was first dissolved in ethanol as a 50 mM stock solution and then dispersed into the 2-HEMA prepolymer prior to curing. The stock solution was added to the prepolymer to reach final beta-carotene concentrations of 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 μM (final ethanol content £ 2 vol%), followed by 5 min bath sonication and 30 min magnetic stirring to ensure homogeneity. The 2-HEMA polymer films containing beta-carotene were manufactured using a silicone mold with an area of 2.25π and average thickness of 0.100–0.120 mm, following contact lens standards of ISO 18369-1. Films were then cured and residual solvent was removed during curing and by vacuum-drying to constant mass under identical drying and hydration conditions.

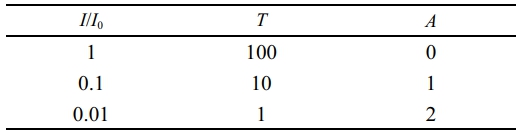

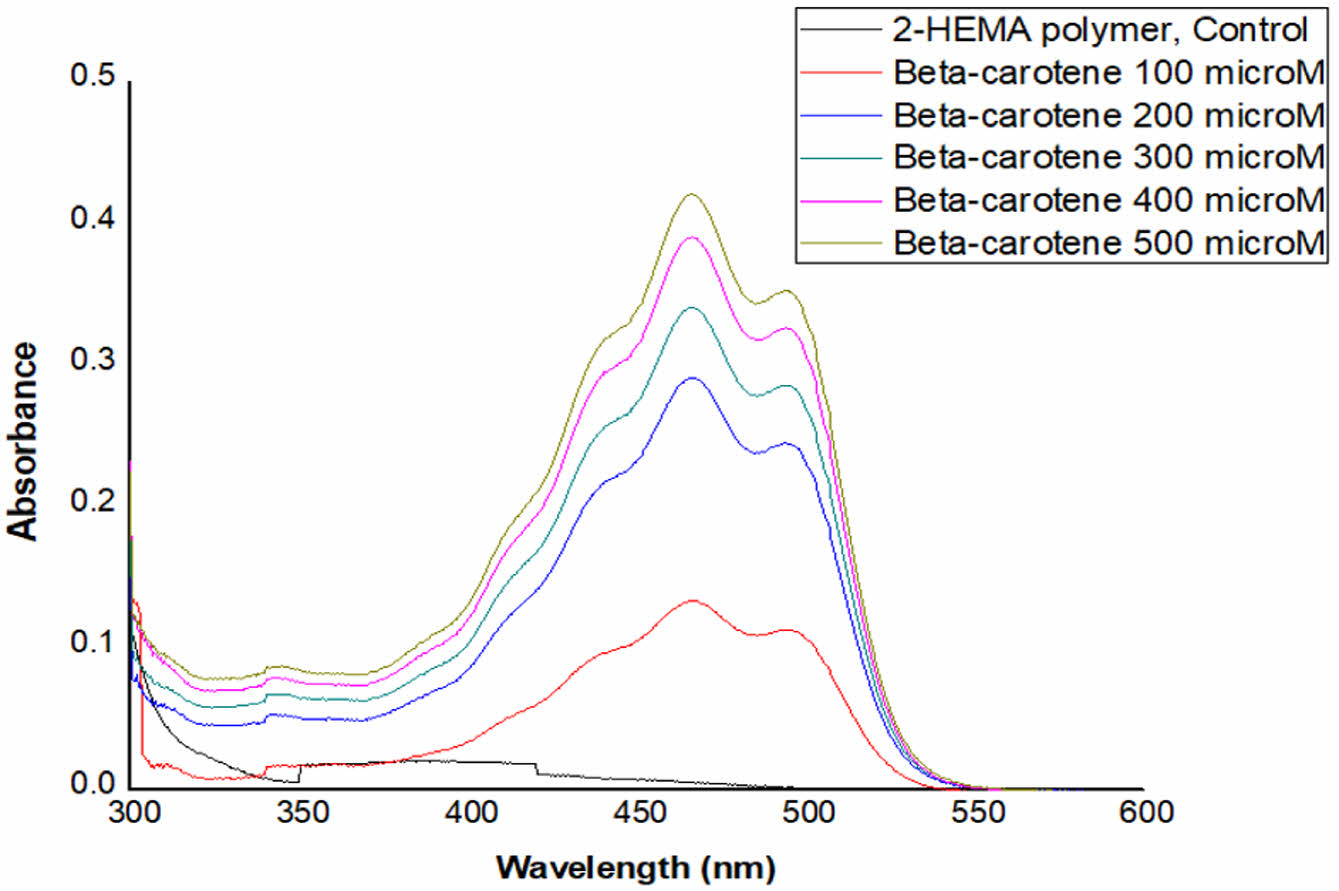

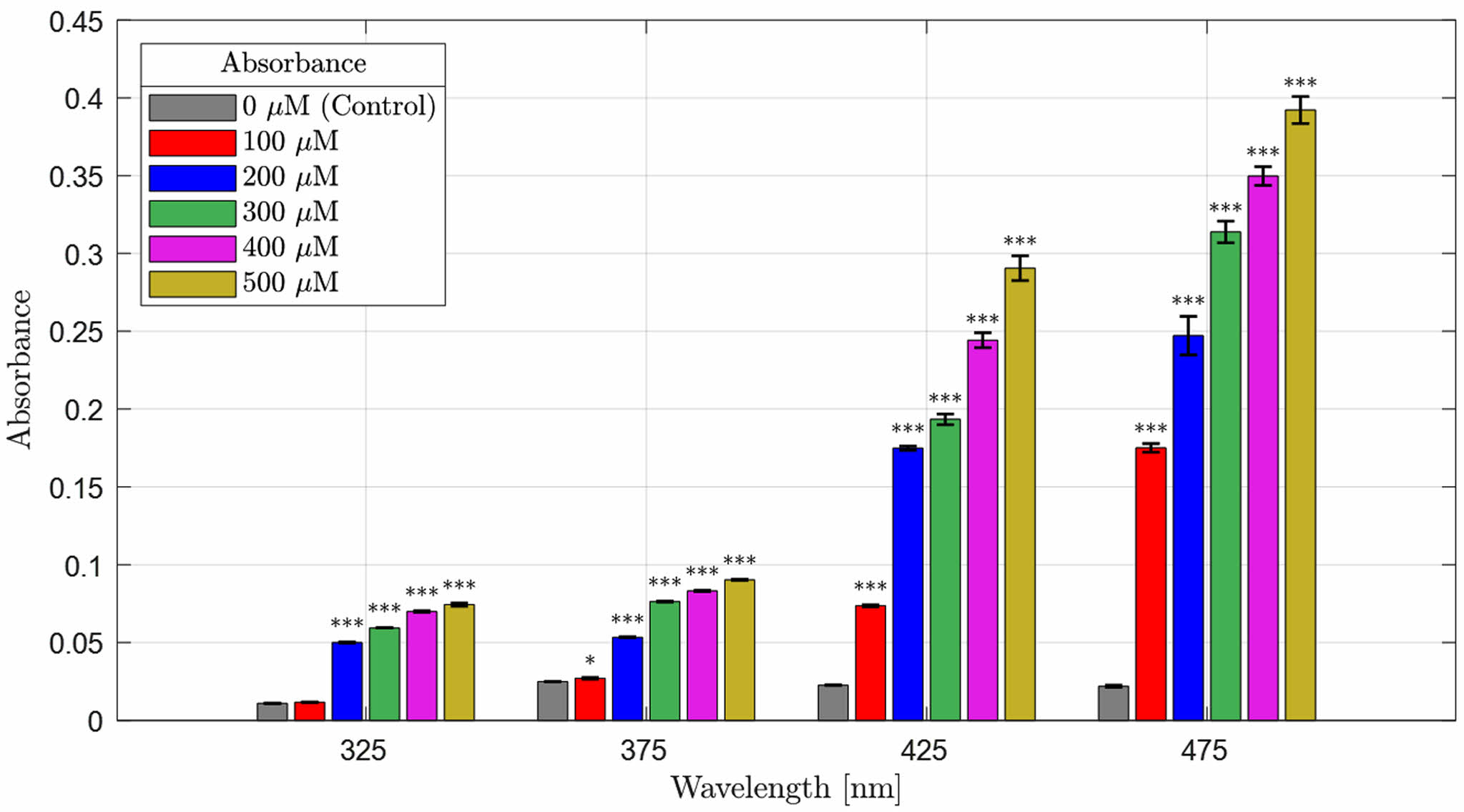

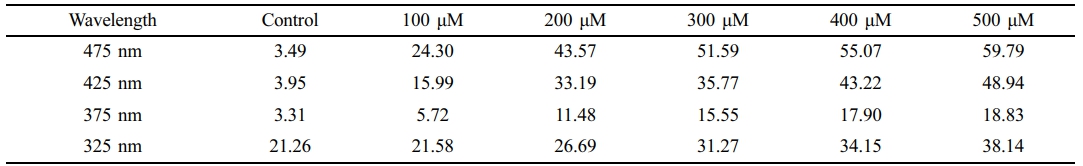

(2) Evaluation of Absorbance Distribution and Absorption Rate of 2-HEMA Polymers Containing Beta-Carotene at Various Molar Concentrations: The absorbance of 2-HEMA polymer films containing beta-carotene was measured in terms of molar concentration. The control group used 2-HEMA polymers without added beta-carotene, while the experimental groups included measurements at 100, 200, 300, 400, and 500 μM. The measurement range was determined to be 300 nm to 600 nm, which includes the blue light region. Based on the measurement results, the absorbance was calculated using the Lambert-Beer law (see Table 1).22

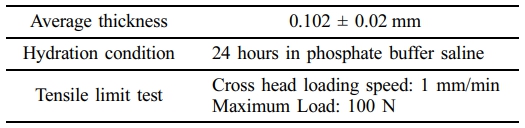

Verification of the physical property changes in 2-HEMA polymer films containing beta-carotene

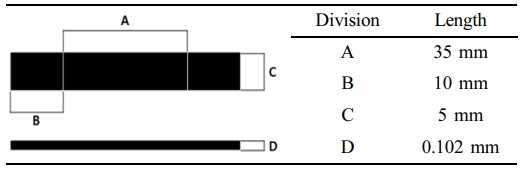

. The physical property changes of 2-HEMA polymer films with varying beta-carotene content were examined. Specimens were prepared according to the contact lens physical property evaluation standards of ISO 18369-4 (see Table 2). Control: 2‑HEMA film with 0 μM beta‑carotene; Experimental: 2‑HEMA film with 500 μM beta‑carotene (identical formulation otherwise) The average thickness of the specimens was set to 0.102 ± 0.02 mm, and measurements were taken up to the ultimate strength. Before testing, the specimens were hydrated in PBS for 24 hours, and the load (N) over time was measured. The tensile speed was set to 1 mm per minute, with a maximum force of 100 N (see Table 3).

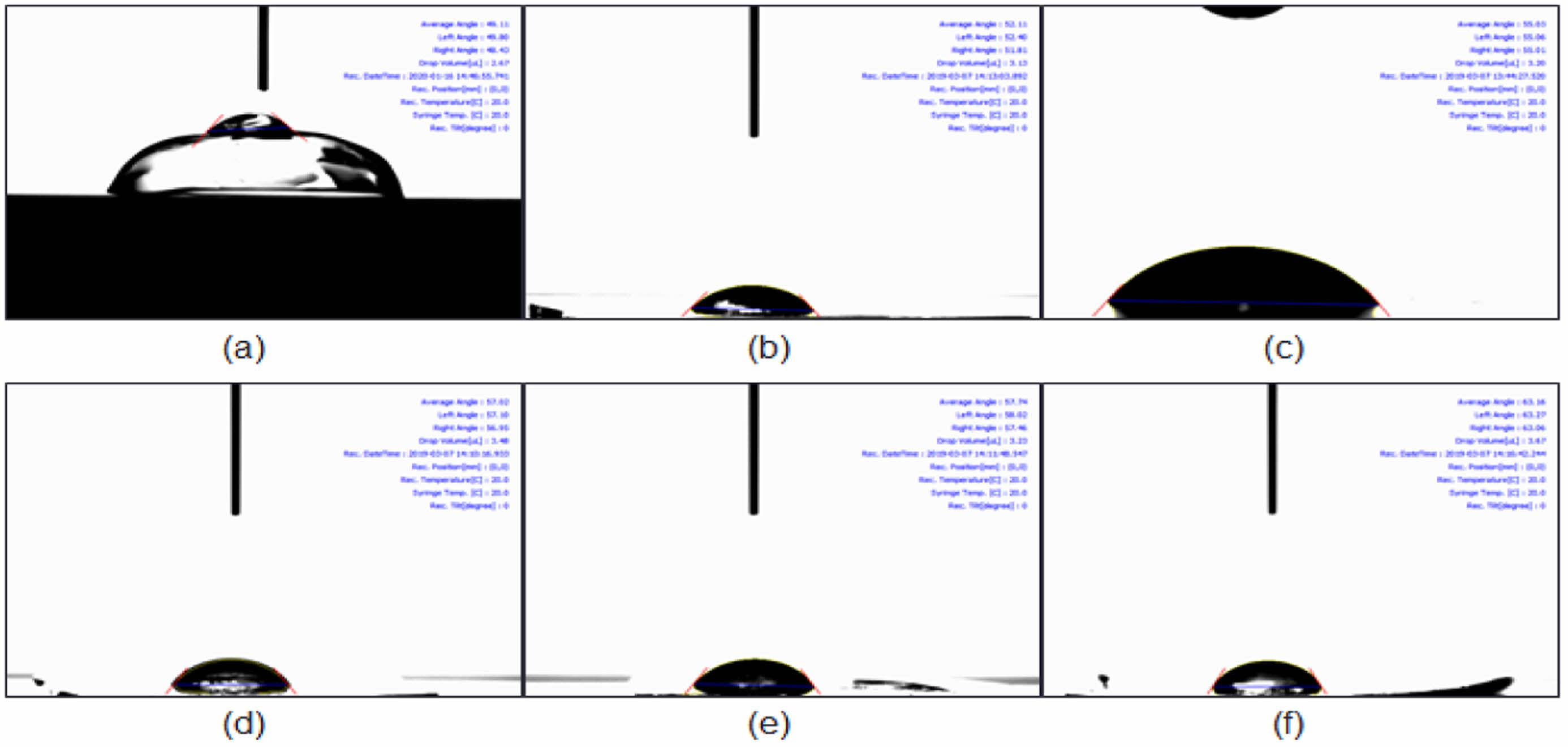

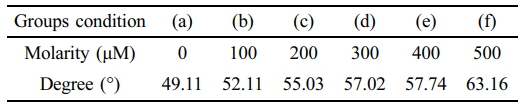

Evaluation of the Hydrophilicity of 2-HEMA Polymer Films Containing Beta-carotene. The hydrophilicity of 2-HEMA polymer films with varying amounts of the hydrophobic substance beta-carotene was observed. To evaluate hydrophilicity, contact angle tests were conducted on the film surfaces. Prior to the tests, the water content standards of contact lenses, ISO-14534, were considered. The control group used commercially available soft contact lenses, while the experimental groups used 2-HEMA polymer films with beta-carotene concentrations ranging from 100 μM to 500 μM. Before testing, the films were hydrated in PBS for 24 hours and then completely dried. The sessile drop method was applied for contact angle measurements to evaluate hydrophilicity.

The sessile drop method is a widely used technique for measuring the contact angle of a liquid on a solid surface.23 This method involves dropping a microliter-scale solution onto the surface and measuring the contact angle of the droplet.23 The contact angle is defined as the angle formed at the contact point between the solid surface and the liquid/gas interface, and it is calculated based on the shape of the droplet.23 In this study, water was used to measure the droplet angle on the surface to evaluate hydrophilicity.

Investigation of Beta-carotene Elution From Beta-carotene-containing 2-HEMA Polymer Films

. 2-HEMA forms a network structure during the polymerization process.24 This structure facilitates the exchange of oxygen and moisture, and when beta-carotene is incorporated, a coacervation effect occurs. The coacervation effect refers to the phase separation of the added substances from the solution when other materials are added to the acrylic polymer or when the temperature is changed. This effect was applied to investigate beta-carotene elution patterns.25 The control group used 2-HEMA polymer films without beta-carotene, while the experimental group used 2-HEMA polymer films containing beta-carotene in the range of 100 μM to 500 μM. Each group was stirred in PBS at 37 ℃ and 200 rpm using a shaking incubator. Measurements were taken after 24, 72, and 120 hours, and absorbance was measured using a UV/vis spectrometer at each time point. The measurement range was set from 300 nm to 600 nm.

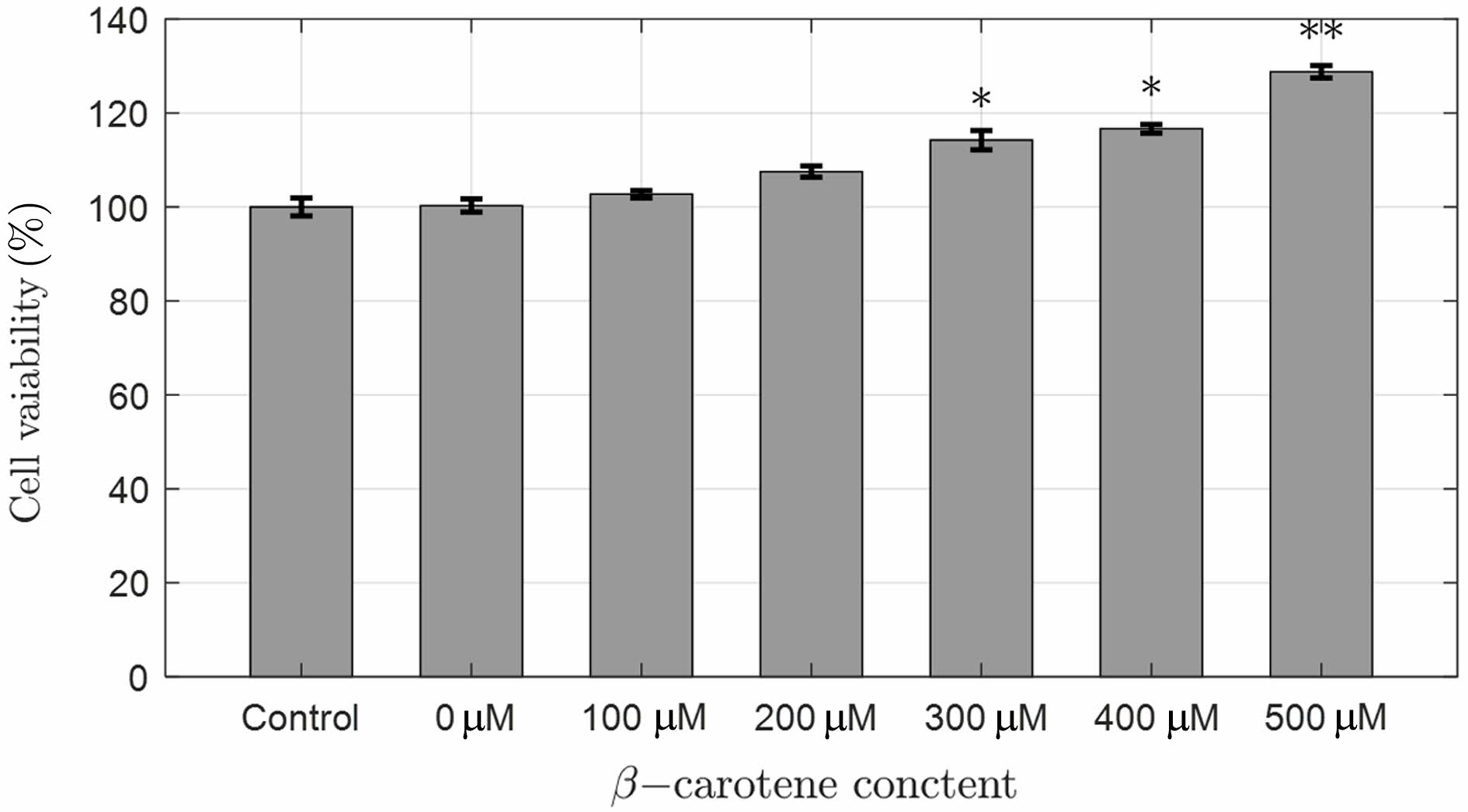

Evaluation of cytotoxicity of Beta-carotene-containing 2-HEMA polymer films. To evaluate the degradation and impact of the drug when beta-carotene, an antioxidant, is added during the polymerization process of 2-HEMA, a cytotoxicity assessment was conducted. For the cytotoxicity evaluation of the film form, an eluate test, which is one of the indirect evaluation methods, was performed. All specimens were soaked in 70% alcohol for 30 minutes, then cleaned using an EO gas sterilizer. After that, to facilitate the hydration process, they were hydrated in sterile PBS for 24 hours. The hydrated specimens were then immersed in 50 mL of medium (DMEM + FBS + penicillin/streptomycin) for 24 hours to extract the eluate. The concentration range of the eluate was measured from 0 μM to 500 μM. The cells used were CRL-4005 cells cultured in T-75 flasks, stained with trypan blue (Gibco, USA), and counted using a hemacytometer. They were then seeded into a 96-well plate at a density of 1×104 cells/200 μL. The cells in the plate were cultured in an incubator for 24 hours, then the medium was replaced with the eluate from the specimens, and further cultured for 24 hours. Finally, CCK-8 was added at a ratio of 1/10 of the total medium volume to react with the adhered cells. After 4 hours, cytotoxicity was measured at a wavelength of 450 nm using a microplate reader.

Statistical Analysis. The experimental results of this study were evaluated for statistical significance using T-test analysis within a 95% confidence interval (*p < 0.05). When there were three or more outcome variables, an ANOVA test was applied.

|

Table 1 The Relationship Between Transmittance and Absorbance Using Lambert-Beer’s Law |

|

Table 3 Experimental Environment for Physical Properties Tests of 2-HEMA Polymer Film |

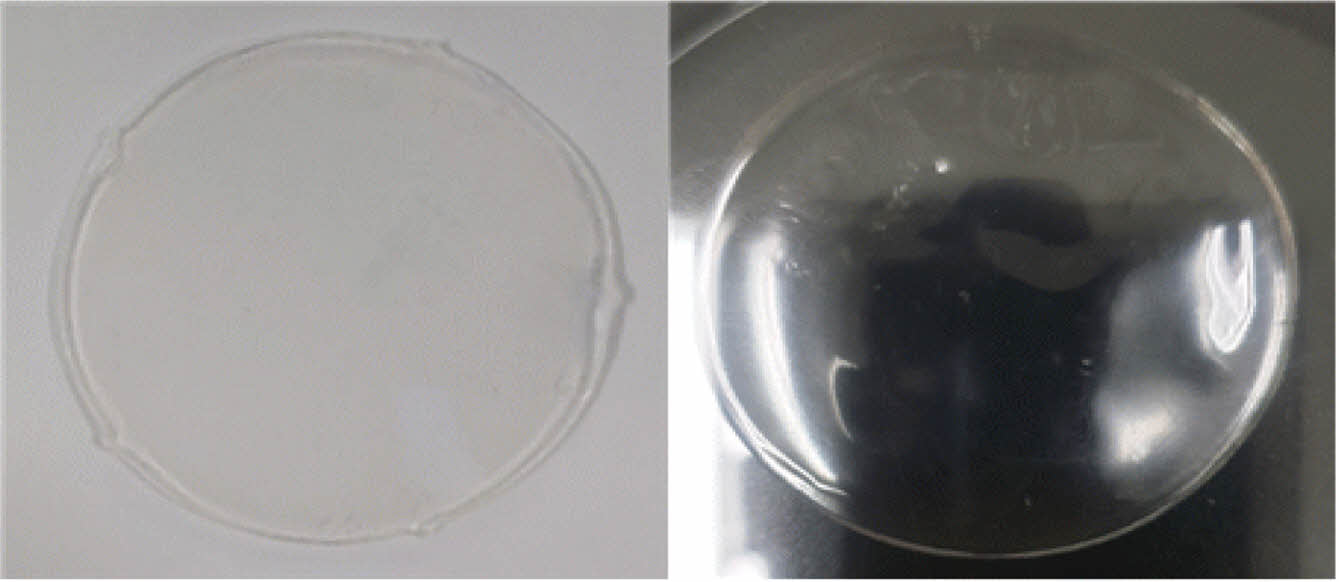

Morphology of 2-HEMA Polymer Films. Figure 1 shows the results of synthesizing 2-HEMA, EGDMA, MA, and AIBN into film form. During the film manufacturing process, depending on the properties of the mold, the 2-HEMA polymer became integrated with the mold during the curing process. As a result, an ideal 2-HEMA polymer film was obtained when a silicone mold was used. Figure 1 illustrates the morphology of the 2-HEMA polymer film before and after hydration.

Absorbance Distribution and Absorption Rate of Beta-Carotene-containing 2-HEMA Polymer Films According to Molar Concentration Content. Figure 2 and Figure 3 show the absorbance distribution and statistical significance evaluation results of beta-carotene-containing 2-HEMA polymer films according to molar concentration ratios. Table 4 shows the absorption rate results calculated using the Lambert-Beer law. The distribution results indicate that the beta-carotene-containing films exhibited absorbance capability across the entire blue light spectrum, with the highest absorbance observed in the 450 nm to 500 nm range. The absorbance of the control group, which did not contain beta-carotene, was minimal in the 300 nm range. The absorption rate was over 43% at concentrations above 200 μM in the 475 nm range and over 43% at concentrations above 400 μM in the 425 nm range. The statistical significance evaluation of the molar concentrations showed a significant difference of 99.999% across the entire blue light spectrum at concentrations above 200 μM, and a significant difference of 95% in the 375 nm range at a 100 μM concentration. No significant difference was observed in the 325 nm range.

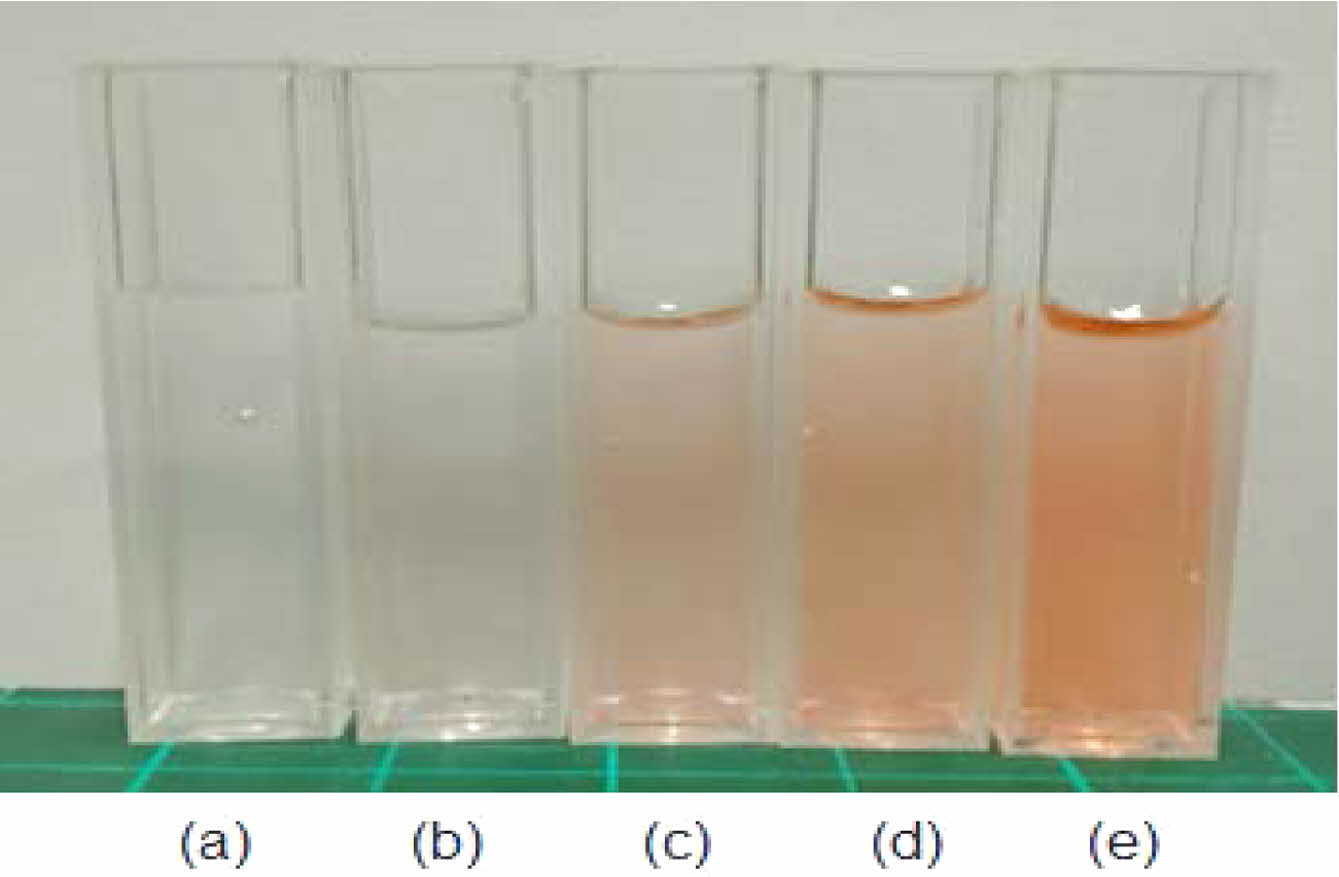

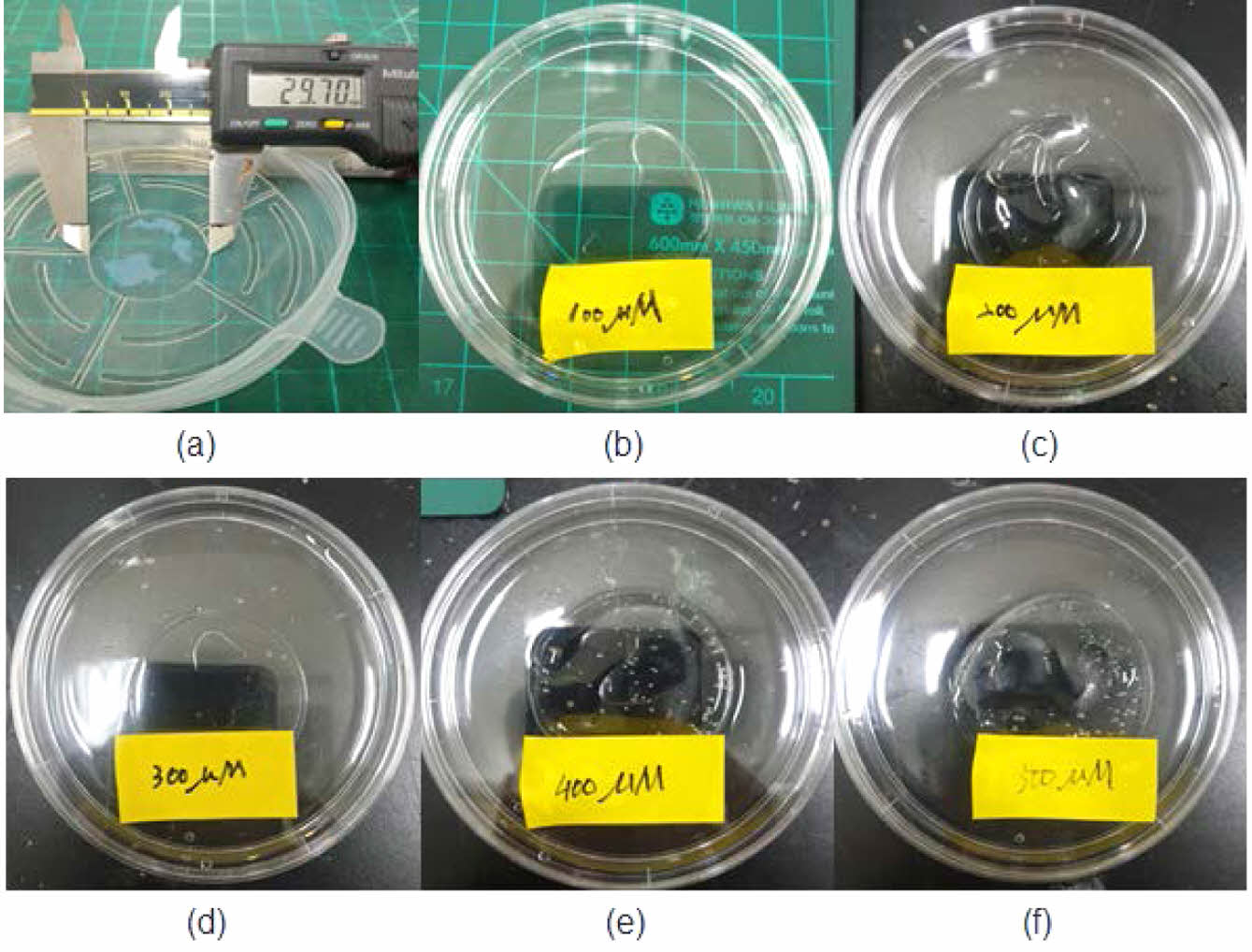

Fabrication Morphology 2-HEMA Polymer Films According to Beta-carotene Content. Beta-carotene imparts an orange-red tint and, at high loadings, can influence the visual appearance of the material. To contextualize color and clarity, we documented both the pre-cure (monomer) mixtures and the post-cure films at a contact-lens-relevant thickness. Complementarily, bright-field optical microscopy of the pre-cure 2-HEMA mixtures (10×/40×; thin observation chamber, ~100–200 μm path length) revealed no micron-scale inclusions (³ 2–3 μm) or emulsified domains across 0–500 μM, indicating no evidence of micron-scale phase separation prior to curing; by contrast, beta-carotene in water (500 μM) produced readily visible aggregates, serving as a positive control. Figure 4 illustrates the concentration-dependent coloration of the pre-cure 2-HEMA mixtures (0–500 μM). Figure 5 shows hydrated, post-cure films prepared to a standardized thickness (»0.10 ± 0.02 mm; ISO 18369-1 series), which remained visually clear without apparent haze or band-like discoloration across all loadings, with background/pattern visibility preserved. At this standardized thickness, films showed no visible change in shape or clarity before versus after hydration (PBS, 24 h) under uniform illumination, consistent with hydrogel behavior at the examined thickness. Consistent with the appearance, the spectral data (Table 4) exhibit a monotonic increase in blue-band attenuation with beta-carotene loading, supporting absorption-dominated behavior and a uniformly dispersed matrix at the micron scale under the tested conditions.

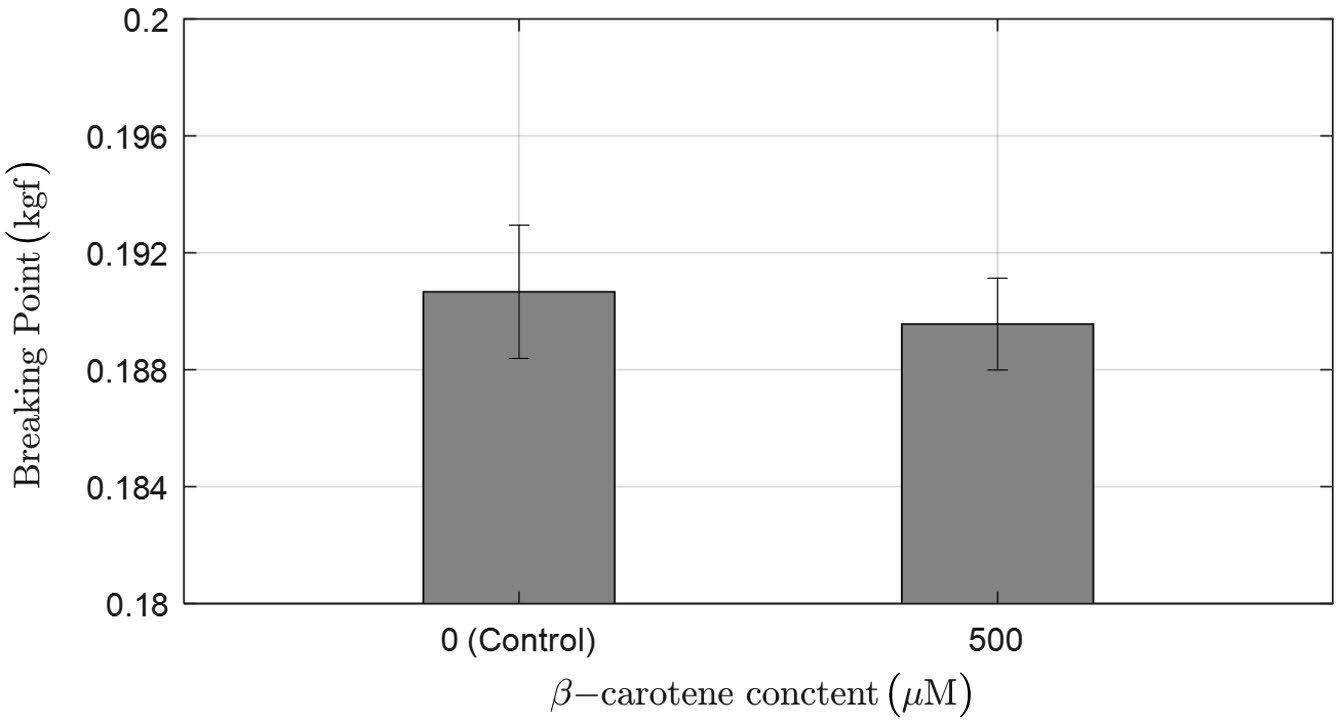

Verification of Changes in Physical Properties of 2-HEMA Polymer Films with Beta-carotene. Figure 6 shows the changes in the physical properties of 2-HEMA polymer films according to the presence and maximum content of beta-carotene. Each group measured the breaking point in kgf units, applying the contact lens physical property standard ISO-18369-4. As a result, both groups measured between 0.18 kgf and 0.21 kgf, which is within the standard specification for contact lenses, and the T-test results showed no significant difference.

Hydrophilicity Evaluation According to Beta-carotene Content. Figure 7 summarizes the static water contact angle (hydrated films). A modest, concentration-dependent increase in contact angle was observed with beta-carotene loading. We interpret this trend as interfacial enrichment of a hydrophobic additive near the air/water interface during curing/hydration—distinct from bulk phase separation—consistent with the maintained macroscopic transparency and monotonic blue-band attenuation (Table 4). While a higher contact angle may influence initial wettability, on-eye comfort depends on multiple surface-related factors; accordingly, we outline practical mitigation strategies (reduced loading, minor hydrophilic comonomers such as NVP/MA, surface conditioning layers such as PVP, and host–guest complexation to limit hydrophobe exposure) to be explored in follow-up studies.26

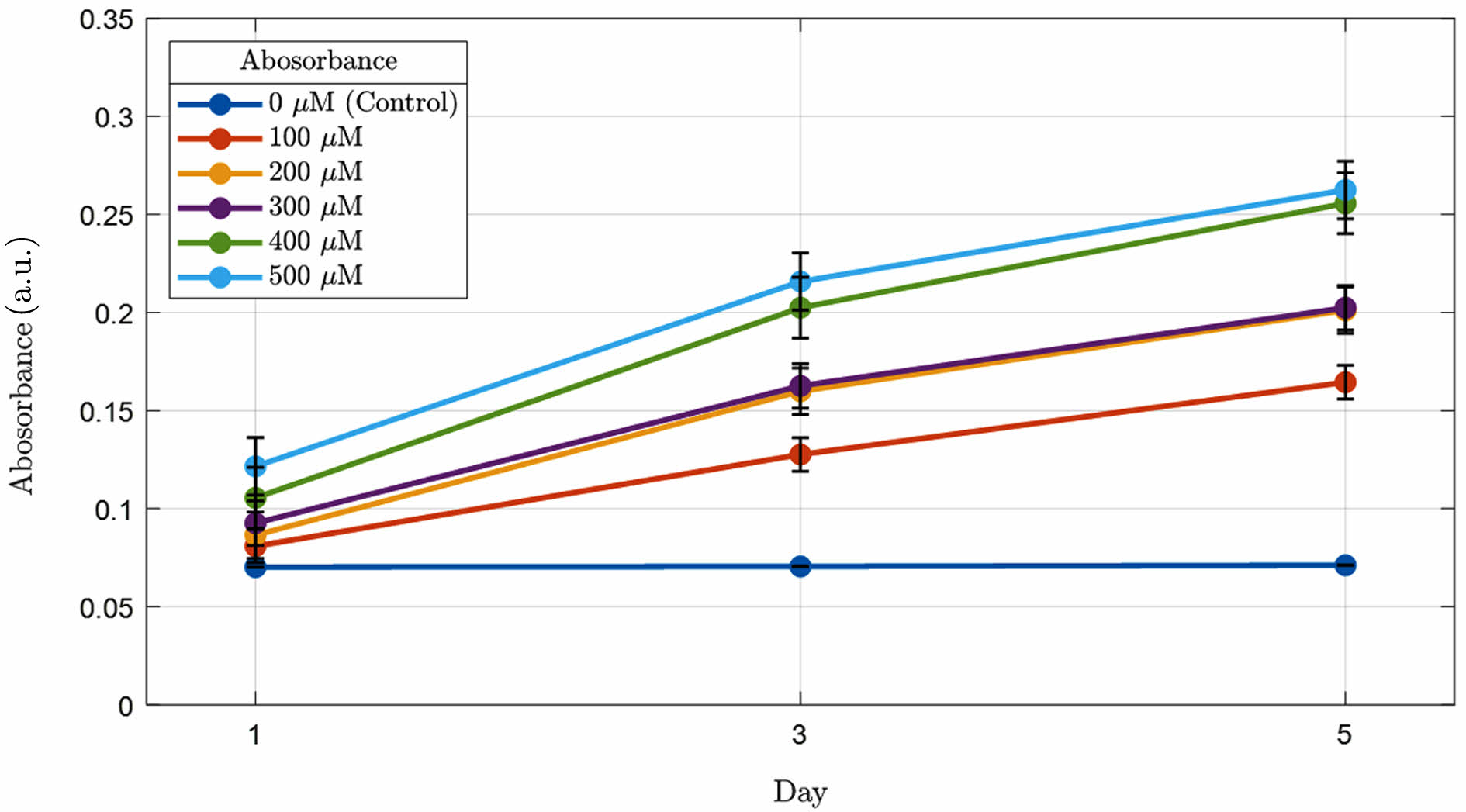

Verification of Beta-carotene Elution from 2-HEMA Polymer Films Based on Beta-carotene Content. Figure 8 shows the beta-carotene elution patterns of 2-HEMA polymer films according to the concentration changes of beta-carotene in the blue light region. The results indicate that the 2-HEMA polymer films without beta-carotene exhibited a small amount of absorbance. This absorbance was measured in the 300 nm range due to the characteristics of 2-HEMA, and there was no change in absorbance over time. The 2-HEMA polymer films containing beta-carotene showed increased absorbance as the beta-carotene content increased, although the increase over time was minimal. An increase in absorbance over time in the blue-light region indicates beta-carotene elution; however, the elution into PBS was minimal yet detectable, while the film’s appearance and blue-band attenuation (Table 4) were unchanged over the same period and no cytotoxicity was observed, supporting that this is a trace-level release without practical impact on the optical function or biocompatibility of the films in our test window.

Cytotoxicity of 2-HEMA Polymer Films According to Beta-carotene Content. Figure 9 shows the cytotoxicity results of 2-HEMA polymer films containing beta-carotene. The results confirmed that there was no cytotoxicity depending on the presence and increasing molar concentration of beta-carotene. Interestingly, cell proliferation occurred at concentrations above 200 μM, which is believed to be due to the antioxidant reaction induced by beta-carotene released from the film in CRL-4005 cells. Additionally, studies have reported that carotenoid compounds enhance wound healing in skin cells.24 T-test evaluation between molar concentrations showed significant differences of 95% at 300 μM and 400 μM, and 99% at 500 μM, demonstrating cell proliferation. Table 5

|

Figure 1 Morphology of 2-HEMA polymer film: (a) before hydration; (b) after hydration. Size: 6.5 π, thickness: 1.53 ± 0.025 (mm). |

|

Figure 2 Absorbance distribution of 2-HEMA polymer including beta-carotene according to molarity |

|

Figure 3 Results of the statistical significance comparison of beta-carotene absorbance in the blue light region (molarity), (n = 5), (***p < 0.001, *p < 0.05). |

|

Figure 4 Before the production of 2-HEMA polymer film according to molarity: (a) 100 μM; (b) 200 μM; (c) 300 μM; (d) 400 μM; (e) 500 μM. |

|

Figure 5 After the production of 2-HEMA polymer film according to molarity: (a) film mold; (b) 100 μM; (c) 200 μM; (d) 300 μM; (e) 400 μM; (f) 500 μM, Size: 3π, Thickness: 0.102 ± 0.02 mm. |

|

Figure 6 Comparison of the breaking point of 2-HEMA polymer film according to the content of beta-carotene (n = 5), (*p > 0.05), Width: 0.5 ± 0.01 (cm), Length measurement: 3.5 ± 0.02 (cm). |

|

Figure 7 Results of contact angle of 2-HEMA polymer film containing beta-carotene ratio: (a) control (0 μM); (b) 100 μM; (c) 200 μM; (d) 300 μM; (e) 400 μM; (f) 500 μM. |

|

Figure 8 Comparison graph of release absorbance of 2-HEMA polymer film containing beta-carotene according to the difference in molarity (n=5). |

|

Figure 9 Cytotoxicity of 2-HEMA polymer film containing beta-carotene according to molarity (n = 4), (**p < 0.01), (*p < 0.05). |

|

Table 4 The Calculat ion Result of Blue Light Absorpt ion Rat e of Molarit y (unit: %) |

In this study, beta‑carotene was incorporated into 2‑HEMA films to evaluate their effectiveness in reducing the transmission of incident blue light (400–500 nm) to the eye and their suitability as contact lens materials.

(1) Absorption Efficiency of Beta-Carotene: Beta-carotene exhibited a high absorption efficiency of over 43% across the entire blue light spectrum (350–500 nm). This indicates that beta-carotene effectively reduces the transmission of blue light through the 2-HEMA polymer film.

(2) Compliance with Contact Lens Standards: When the films were produced according to contact lens manufacturing standards, they maintained transparency while meeting the requirements for blue light reduction.

(3) Physical Properties: The physical properties of the 2-HEMA polymer films, such as mechanical strength and flexibility, were not adversely affected by the addition of beta-carotene up to a maximum concentration of 500 μM. This suggests that the structural integrity is maintained when beta-carotene is used in contact lenses.

(4) Beta-carotene Elution and Stability: The elution of beta-carotene from the 2-HEMA polymer films was minimal, indicating that the active ingredient is stably retained within the polymer matrix. This is beneficial for maintaining the long-term efficacy of the contact lenses while minimizing beta-carotene elution.

(5) Cytotoxicity: Cytotoxicity tests showed no cell toxicity at all concentrations of beta-carotene. Interestingly, cell proliferation increased at concentrations above 200 μM, likely due to the antioxidant properties of beta-carotene. This suggests that beta-carotene is biocompatible and may promote cell health under certain conditions.

(6) Hydrophobicity: A drawback observed was the increase in hydrophobicity of the films with higher concentrations of beta-carotene. Contact angle measurements indicated that high concentrations of beta-carotene increased the hydrophobicity of the film surface, which could cause discomfort for the wearer. Therefore, further research is needed to improve the hydrophilicity of the films to ensure comfort during wear.

In conclusion, 2-HEMA polymer films containing beta-carotene effectively reduce blue light transmission, maintain appropriate physical properties, and are beneficial to cells. Thus, these films are suitable for use as blue light-reducing contact lenses. However, to optimize their use as contact lenses, further research is needed to improve the hydrophilicity of the films to ensure wearer comfort. Further research is needed to improve the hydrophilicity of the films and ensure wearer comfort.

- 1. Seonho, J.; Hee, Y. LED Industry Trends and Policy Directions. IT SoC Mag. 2009, 31, 9-14.

- 2. Yong, C.; Hyun, J. Comparative Study on Luminous Flux of Diffusion LED Lamp and Incandescent Lamp by Angle. J. Korean Inst. Illum. Electr. Install. Eng. 2014, 28, 32-39.

-

- 3. Wolf, E. The Radiant Intensity From Planar Sources of Any State of Coherence. J. Opt. Soc. Am. 1978, 68, 1597-1605.

-

- 4. Lee, J. Y.; Yun, E. J.; Kim, S. M.; Hwang, H. K.; Park, G. J. The Changes of the Eye and a Correlation Depending on Watching a Smartphone and Taking in Alcohol. J. Korean Ophthalmic Opt. Soc. 2013, 18, 473-479.

-

- 5. Smick, K.; Villette, T. Blue Light Hazard: New Knowledge, New Approaches to Maintaining Ocular Health—Report of a Roundtable; Essilor of America: Dallas, 2013.

- 6. Yu, Y. G.; Choi, E. J. A Study on Blue Light Blocking Performance and Prescription for Blue Light Blocking Lens. J. Korean Ophthalmic Opt. Soc. 2013, 18, 297-304.

-

- 7. Nguyen, Q. K.; Glorieux, B.; Sebe, G.; Yang, T. H.; Yu, Y. W.; Sun, C. C. Passive Anti-leakage of Blue Light for Phosphor-converted White LEDs with Crystal Nanocellulose Materials. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13039.

-

- 8. Park, S. I. The Effect of Brown Tinted or UV-A Blocking Ophthalmic Lens Against the Photooxidation of A2E, a Lipofuscin in Retina. J. Korean Ophthalmic Opt. Soc. 2012, 17, 91-97.

-

- 9. Jung, M. H.; Yang, S. J.; Yuk, J. S.; Oh, S. Y.; Kim, C. J.; Lyn, J.; Choi, E. J. Evaluation of Blue Light Hazards in LED Lightings. J. Korean Ophthalmic Opt. Soc. 2015, 20, 293-300.

-

- 10. Klein, R. J.; Zeiss, C.; Chew, E. Y.; Tsai, J. Y.; Sackler, R. S.; Haynes, C.; Henning, A. K.; SanGiovanni, J. P.; Mane S. M.; Mayne, S. T.; Bracken, M. B. Ferris, F. L.; Ott, J. Barnstable, C.; Hoh, J. Complement Factor Hpolymorphism in Age-related Macular Degeneration. Science 2005, 308, 385-389.

-

- 11. Wilcox, C. S.; Welch, W. J.; Murad, F.; Gross, S. S.; Tayler, G.; Levi, R.; Schmidt, H. H. Nitric Oxide Synthase in Macula Densa Regulates Glomerular Capillary Pressure. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1992, 89, 11993-11997.

-

- 12. Leung, T. W.; Li, R. W. H.; Kee, C. S. Blue-light Filtering Spectacle Lenses: Optical and Clinical Performances. PLoS One 2017, 12, e0169114.

-

- 13. Moreddu, R.; Vigolo, D.; Yetisen, A. K. Contact Lens Technology: From Fundamentals to Applications. Adv. Healthc. Mater. 2019, 8, 1900368.

-

- 14. Park, S. H.; Lee, I. Y.; Jeon, I. C. Survey on the Usage Status of Vision Correction Glasses in Korea (2013–2019). J. Korean Ophthalmic Opt. Soc. 2019, 21, 509-523.

-

- 15. Zloh, M.; Esposito, D.; Gibbons, S. Helical Net Plots and Lipid Favourable Surface Mapping of Transmembrane Helices of Integral Membrane Proteins: Aids to Structure Determination of Integral Membrane Proteins. Internet J. Chem. 2003, 6, 2.

-

- 16. Musgrave, C. S. A.; Fang, F. Contact Lens Materials: A Materials Science Perspective. Materials 2019, 12, 261.

- 17. Cabral, L. M.; Castro, R. N.; de Moura, R. O.; Kümmerle, A. E. Synthesis and Evaluation of Antiproliferative Activity, Topoisomerase IIα Inhibition, Dna Binding and Non-clinical Toxicity of New Acridine–thiosemicarbazone Derivatives. Pharmaceuticals 2022, 15, 1098.

-

- 18. Krinsky, N. I.; Johnson, E. J. Carotenoid Actions and Their Relation to Health and Disease. Mol. Aspects Med. 2005, 26, 459-516.

-

- 19. Palozza, P.; Krinsky, N. I. Antioxidant Effects of Carotenoids In Vivo and In Vitro: An Overview. Methods Enzymol. 1992, 213, 403-420.

-

- 20. Tanaka, T.; Shnimizu, M.; Moriwaki, H. Cancer Chemoprevention by Carotenoids. Molecules 2012, 17, 3202-3242.

-

- 21. Carrier, P.; Deschambeault, A.; Audet, C.; Talbot, M.; Gauvin, R.; Giasson, C. J.; Germain, L. Impact of Cell Source on Human Cornea Reconstructed by Tissue Engineering. Invest. Ophthalmol. Vis. Sci. 2009, 50, 2645-2652.

-

- 22. Kim, K. J.; Kim, H. S.; Lee, D. U.; Lee, W.; Harris, D. C. Analytical Chemistry, 2nd ed.; Free Academy: Seoul, 2004; pp 385-392.

- 23. Adamson, A. W.; Gast, A. P. Physical Chemistry of Surfaces, 6th ed.; Wiley-Interscience: New York, 1997.

- 24. Kim, S. J.; Choi, S. H. Research Trends on the Application Possibility and Rheological Properties of Coacervate. NICE (News Inf. Chem. Eng.) 2019, 37, 166-172.

- 25. Lee, S. H.; You, R.; Yoon, Y. I.; Park, W. H. Preparation and Characterization of Acrylic Pressure-sensitive Adhesives Based on UV and Heat Curing Systems. Int. J. Adhes. Adhes. 2017, 75, 190-195.

-

- 26. Dash, R.; Acharya, C.; Bindu, P. C.; Kundu, S. C. Antioxidant Potential of Silk Protein Sericin Against Hydrogen Peroxide-induced Oxidative Stress in Skin Fibroblasts. BMB Rep. 2008, 41, 236-241.

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2025; 49(6): 846-854

Published online Nov 25, 2025

- 10.7317/pk.2025.49.6.846

- Received on Sep 15, 2025

- Revised on Sep 29, 2025

- Accepted on Oct 17, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusions

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Hong Jin Choi and Jeong Koo Kim

-

Department of Biomedical Engineering, Inje University, Gimhae, Gyeongnam 50834, Korea

- E-mail: hjchoi@inje.ac.kr, jkkim@inje.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0001-9170-2670, 0000-0001-9898-6581

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.