- Tungsten Doped Manganese Nanoflower for Photothermal Therapy

Kushal Chakraborty# , Jeong Man An*,# , and Yong-kyu Lee**,†

Department of IT and Energy Convergence (BK21 FOUR), Korea National University of Transportation, Chungju 27470, Korea

*Department of Bioengineering, College of Engineering, Hanyang University, Seoul 04763, Korea

**Department of Chemical & Biological Engineering, Korea National University of Transportation, Chungju 27470, Korea- 광열치료를 위한 텅스텐이 도핑된 망간 나노플라워

한국교통대학교 교통에너지융합학과, *한양대학교 생명공학과, **한국교통대학교 화공생물공학과

Reproduction, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form of any part of this publication is permitted only by written permission from the Polymer Society of Korea.

Pristine manganese nanoflowers (MNF) have potential applications in photothermal therapy. The objective was to fine-tune the morphology to reach the desired temperature while avoiding permanent damage, a goal successfully accomplished through tungsten doping. In this study, we effectively incorporated tungsten metal into the flower morphology, resulting in defects and the formation of secondary mesopores within the channel, which subsequently led to a temperature reduction of nearly 20 ℃. The flawed surface clearly exhibited a peak in the mesopore-micropore region, which can be linked to the introduction of foreign metal doping. This approach to doping can be extensively employed to adjust the molecular structure during the application of photothermal therapy treatment.

순수한 망간으로 이루어진 나노플라워(MNF)는 광열 치료에 응용할 수 있는 잠재력이 있다. 정상조직의 영구적인 손상을 피하면서 암세포의 광열치료를 위한 원하는 온도에 도달하도록 나노플라워의 형태를 미세 조정하는 것이 우리 연구의 목표였으며, 텅스텐 도핑을 통해 이 목표를 성공적으로 달성했다. 이 연구에서 우리는 텅스텐 금속을 나노플라워에 효과적으로 도핑하여 표면과 내부에 결함을 발생시키고 메조 기공을 형성하여 광열 최대 온도를 20 °C 낮췄다. 결함이 있는 표면은 메조 기공-미세 기공 영역에서 피크를 분명히 보였으며, 이는 외부 금속 도핑의 도입과 관련이 있다. 이러한 도핑 접근법은 광열 치료법을 적용하는 동안 분자 구조를 조정하는 데 광범위하게 사용될 수 있다.

Pristine manganese nanoflowers (MNF) were optimized for photothermal therapy by doping them with tungsten to control heat generation. The doping introduced structural defects and secondary mesopores, lowering the temperature by nearly 20 ℃. This strategy demonstrates how foreign metal incorporation can fine-tune nanostructures for safer and more effective therapeutic applications.

Keywords: manganese nanoflower, tungsten, nanoparticles, near infrared, mesopores, photothermal therapy.

This research was supported by the Basic Science Research Program through the National Research Foundation of Korea (NRF), funded by the Ministry of Education (Grant No. 2021R1A6A1A03046418). Additional support was provided by the NRF, funded by the Ministry of Science and ICT (MSIT) of the Korean government (Grant Nos. RS-2024-00405287 and 2021R1A2C2095113).

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Since normal phototherapy is a well-established approach in the field of anticancer therapeutics, the main qualm is circling around the choice of materials. There are several materials reported including gold nanoparticles,1 iron oxide nanoparticles,2 carbon nanotubes,3 etc. The idea lies in this approach on the capability of the materials to absorb the light and successfully converting it into heat which in turns creates irreversible damage in tumour microenvironment. “Killing the cancer cells”, is the first call, but the surrounding moiety should get minimum effects from this phenomenon, this drives the chemists to search for facile approaches and new materials.

In the dominion of scholarly literature, the examination of nanocarriers, including quantum dots, carbon nanotubes, liposomes, micelles, gold nanoparticles, polymeric and solid lipid nanoparticles, dendrimers, mesoporous silica nanoparticles, and self-emulsifying nano-drug delivery systems, has emerged as advantageous in the fields of cancer therapy and diagnosis; however, each possesses its own significant shortcomings.4 Amidst these significant challenges are the shadows of dose-related toxicity, the uncertain nature of drug bioavailability, the intricate barriers of permeability, the careful balance of biocompatibility, the harsh reality of instability, the subtle leakage of drugs, the rapid release that deceives, the daunting issue of drug resistance, and the complex interplay of pharmacodynamic and pharmacokinetic characteristics. Thus, it become a matter of utmost importance and pressing need to devise a more potent means to convey the remedies unto the afflicted tumour site with efficacy most assured. Scholars have been delving into diverse and ingenious means of delivery, seeking to enhance the noble effects of chemotherapy by contemplating the multifaceted nature of their nanostructures.5

The considerations of a living being and its internal stimulations can be a cause of downfall while implementing the synthetic strategy of inorganic nanomaterials and there is no fight when we consider the external stimuli over the internal one as it is far more comprehensive while controlling the spatial and temporal behaviour of the nanomaterial,6 and until the external perturbation arrives, the nanomaterial remains inactive.7 In contrast to the rays of ultraviolet and the visible spectrum, the light of near infrared possesses photons of a lengthened wavelength and a lesser energy.8 This trait aids NIR light in its descent deeper into the living flesh, yet unfortunately NIR photons lack the vigour to perform numerous photochemical reactions, for they possess not sufficient energy. This quandary may find resolution through devices of upconversion and the pretence of two-photon absorption.9

Upconversion nanoparticles exhibit a remarkable capability to transform the subtle touch of near-infrared light into the vivid colours of visible and ultraviolet light, by absorbing multiple photons and converting them into a single, high-energy photon.10

Besides these two mechanisms, the system responsive to NIR light also adheres to the mechanism of the photothermal effect, which lies at the very heart of PTT.11

In this instance, materials of a delicate nature, attuned to the grasp of light, convert the subtle radiance of near-infrared light into warmth, which may be directed to a chosen locus for hyperthermia. When minuscule materials serve as carriers for the delivery of remedies, those structures, ignited by the heat, transform to liberate their precious contents. When nanomaterials serve as agents of photothermal might, the heat they wield can smite or consume the cells of tumours directly. To craft a system of merit for PTT, the agents of photothermal nature must fulfil certain conditions: they ought to absorb the light of near-infrared hue, convert such illumination to heat with great efficiency, and possess the virtues of biocompatibility and biodegradability.12

Manganese could be found in different oxidation states including Mn2+, Mn3+, Mn4+, Mn5+, Mn6+ and Mn7+.13–15 Utilising these oxidation states, we can reengineer a moiety which solely cater our purposes. Amongst these, Mn2+ is the most stable oxidation state bearing the electronic configuration as [Ar] 3d.5 With a half-filled d orbital, Mn is prone to show some unprecedented activities during complex formation. It also makes it stable due to augmented exchange potential and symmetry of the d subshell. It’s crucial to mention that Mn also transported throughout our body by divalent metal transporter-1.16

In biological premise, manganese serves as an essential micronutrient for managing the normal cell functionalities and mainly to adjust with oxidative stress.17

In the domain of inorganic nanomedicines, where oftentimes one encounters nanoparticles or nanomaterials, the threat they pose may be persuaded by their very physicochemical attributes, including dimensions, form, surface charge, and the materials that cloak their essence. These attributes do hold a most vital part in the communion with cells and tissues. Verily, certain studies have shown that Manganese Oxide Nanoparticles (MON) may act as an agent of the chemodynamic therapy (CDT),18 displaying a aggressive cytotoxicity towards the malignant cells, through a reaction akin to Fenton,19 reliant upon the principle of H2O2 and GSH at particular measures. Fortune favours the normal cells, as their exposure to H2O2/GSH is less, resulting in a reduced impact of MON compared to malignant cells, thereby protecting the healthy from its effects.20

Moreover, the examination of serum biochemistry and the histopathological findings of the heart, liver, and kidneys did reveal naught but trivial irregularities in the principal organs when set against the norm of healthy mice, thus underscoring the commendable harmony of the tissues in question.21

In the realm of science, where the minuscule reigns, nanomaterials have emerged as noble contenders for a multitude of biomedical pursuits. Amongst these, manganese dioxide, known as MnO2, shines brightly, esteemed for its gentle nature and low toxicity.22

Yet, the enduring peril of these substances linger still. Unbeknownst and do demand further inquiry. Thus, to weigh the risky nature of diverse nanomaterials is of utmost importance to fathom their possible import in the cancer therapeutics.

In environment, MnO2 exhibits 5 distinct phases including α, β, γ, δ, and ε. These polymorphs exist by reorganising basic MnO6 unit forming either layer or chain/tunnel morphologies.23

They have different characteristics. In photothermal therapy, they are utilised as they possess excellent capability of transforming the light energy to heat, attributed to the MnO2 centres. But pristine nanoflowers can reach up to 80 ℃ which can create significant alterations in the tumour microenvironment as well as towards the healthy cells and tissues. Ablative hyperthermia was the target for this research,24 so doping was introduced to create a structure which can be affective as well as non-cytotoxic towards the normal cell. Transition metal such as tungsten is relatively inert and it increases the structural integrity when incorporated into nanomaterials, that’s why it was chosen. Here, we report a tungsten doped manganese nanoflower which shows potential photothermal activity that can be exploited.

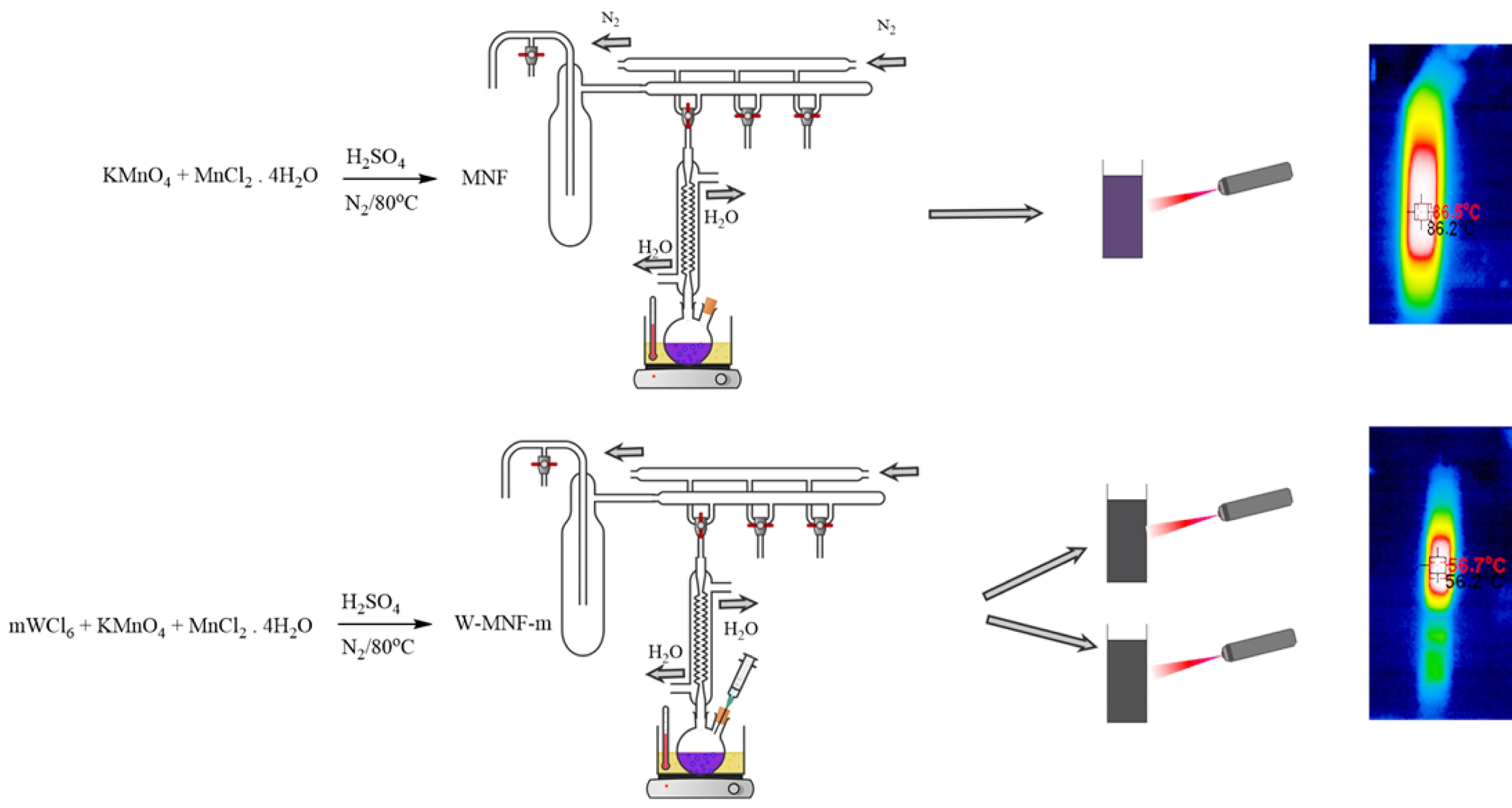

Scheme 1. Tungsten doped manganese nanoflowers for photothermal therapy.

Materials. Commercial reagents and solvents were purchased from accredited supplier (Sigma-Aldrich) and used without further purification: Manganese (II) chloride tetrahydrate (MnCl2·4H2O)≥99%, tungsten hexachloride (WCl6)≥99% trace metal basis, sulphuric acid (H2SO4) 99.999%, 3-[4,5-dimethylthiazol-2yl]-2,5-diphenyl tetrazolium bromide (MTT). Potassium permanganate (KMnO4) S.P.C GR Reagent was bought from Shinyo pure chemicals CO. LTD. DPBS was purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific. The solvents were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich with anhydrous HPLC grade: ethanol, dimethyl formamide and used without further purification. For general purpose, double distilled water was used (Milli-Q, Merck, USA). 4T1 metastatic breast cancer cell lines were purchased from the ATCC (Seoul, South Korea).

Characterisation. The absorption spectra of sample were obtained using a UV-visible absorption spectrophotometer (Optizen 2120 UV spectrophotometer, Mecasys). FESEM imagery was acquired using a JEOL (JSM-7610F) ultra-high resolution field emission scanning electron microscope. X-ray diffraction spectra were observed by Bruker D-2 phaser mini-X-ray diffractometer using Cu-Kα radiation (λ=1.5418 Å) and operating at 30 kV and 10 mA. Infrared spectroscopy was acquired using Agilent Technologies (Cary 610/660) microscope FTIR spectrometer, powdered sample was grinded with KBr to form pellet (1:99 wt%). X-Ray photoelectron spectroscopy was performed using a Ulvac-PHI (PHI GENESIS) X-ray photoelectron spectrometer. BET experiments were performed using a Micromeritics (3Flex) surface analyser at 77K in N2. Before experimentation, the sample was degassed at 150 ℃ for 12 hours at vacuum. BJH (Barrett-Joyner-Halenda) method was implemented to compute the pore size. For absorbance, a SYNERGY HTX microplate reader was used. For photothermal treatment, PSU-H-LED 808 nm laser was used.

Synthesis of Pristine Manganese Nanoflower. The synthesis of pristine nanoflower was carried out in a wet chemical oxidation process. Previously reported method25 was modified and implemented. KMnO4 (2.016 g) and MnCl2·4H2O (0.7638 g) was mixed with 150 mL of DIW until it becomes completely soluble. Then 2.5 mL of concentrated H2SO4 was added dropwise over 10 minutes and the temperature was risen to 80 ℃. This condition was maintained for 90 minutes and in N2 atmosphere. Finally, it was cooled down to the room temperature and washed with water and ethanol for several times until the pH of the filtrate reaches neutral. Then the product was vacuum dried and marked as MNF for future experiment.

Synthesis of Tungsten Doped Manganese Nanoflower. Tungsten doping onto MnO2 framework was done via wet chemical procedure.26 Briefly, KMnO4 (2.016 g) was mixed with two different portions of WCl6 (0.3060 and 1.5307 g) with 100 mL DIW. Then MnCl2·4H2O (0.7638 g) was solubilise in 10 mL of DIW and added to it. Then 2.5 mL of concentrated sulphuric acid was added dropwise over 10 minutes and temperature was risen to 80 ℃. This condition was maintained overnight and carried out in dark condition. Finally, it was cooled down, washed with DIW several times until the filtrate pH was neutral and vacuum dried and marked as W-MNF-0.3060 and W-MNF-1.5307 for future experiment.

Photothermal Experiment Under NIR Laser. MNF and W-MNFs were dissolved in DPBS with different sample concentration and irradiated with 808 nm laser with different power and time. Temperature was recorded at a predetermined interval and plotted.

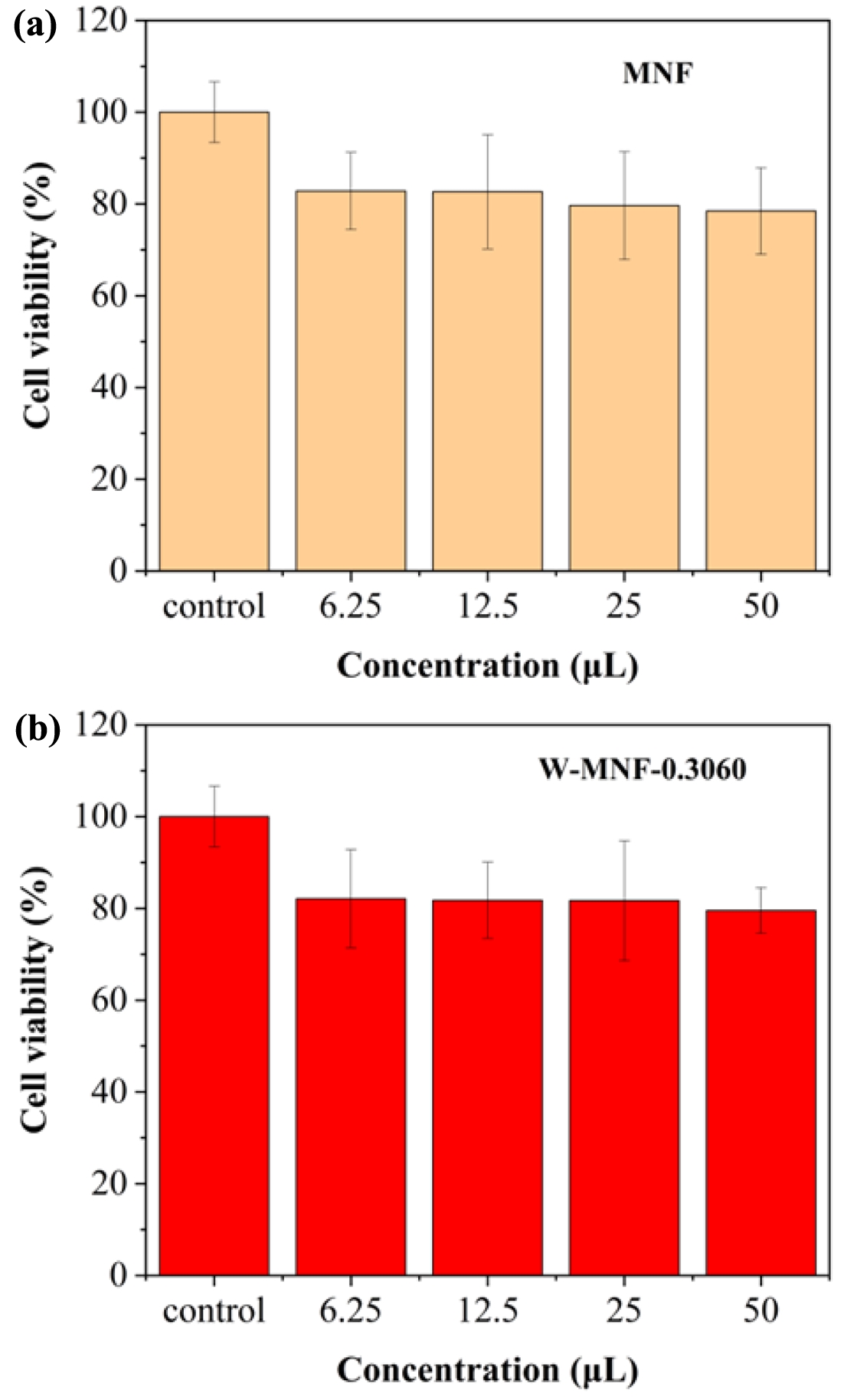

In Vitro Cell Cytotoxicity Assay. The cell viabilities of 4T1 cell lines exposed to MNF and W-MNF-0.3060 were measured by MTT cell proliferation assay. Cells were seeded in a 96 well plate (3×104 cells/well) and incubated for 24 hours. Later different concentrations of W-MNF-0.3060 were added to the 96 well plate and with the medium used as control. After that, the cell solutions were incubated for another 24 hours in dark condition. After that MTT reagent was added (20 μL) and again incubated for another 4 hours. Finally, the cell viability was observed by measuring the absorbance at 535 nm using microplate reader.

Cell viability (%) = {(absorbance from sample treated cells)/(absorbance from the control cells)}×100

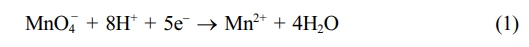

Morphology Analysis. To synthesise the manganese dioxide nanoflowers, initially the redox chemistry was applied. When oxidised by potassium permanganate, manganese chloride can generate different phases. In this case, potassium permanganate first gets reduced in acidic medium to form Mn2+. This phenomenon happens through an intermediate phase (MnO3)2-SO4. Then this Mn2+ is combined with the Mn source of manganese dichloride tetrahydrate to form MnO2.27

Possible reaction as follows:

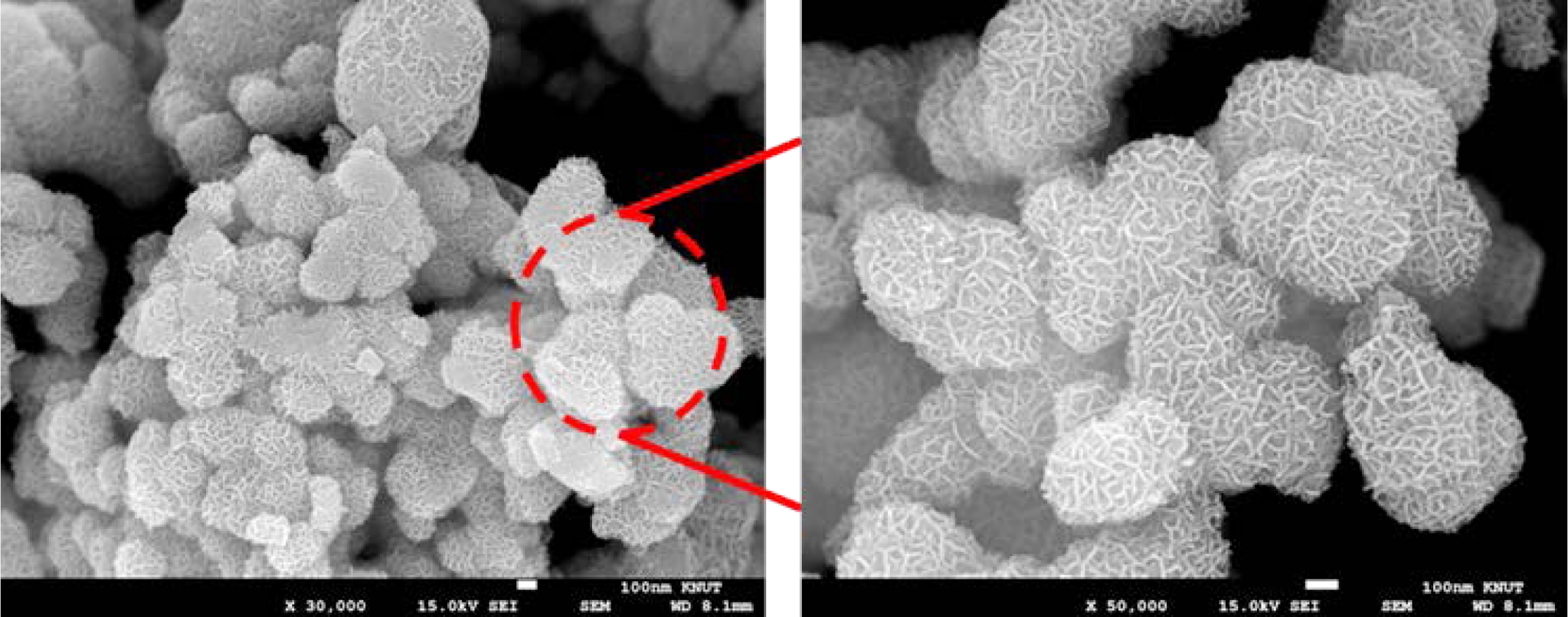

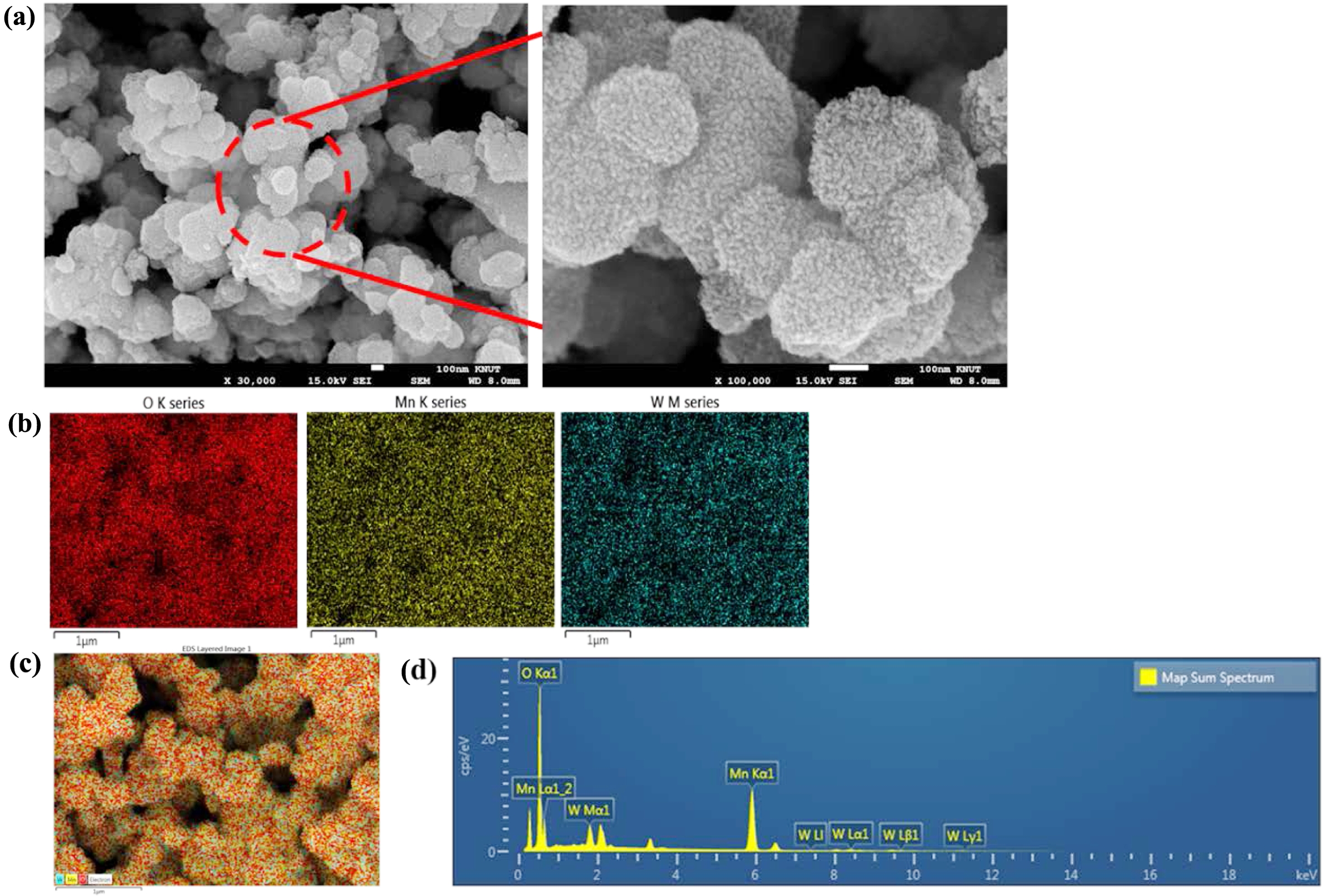

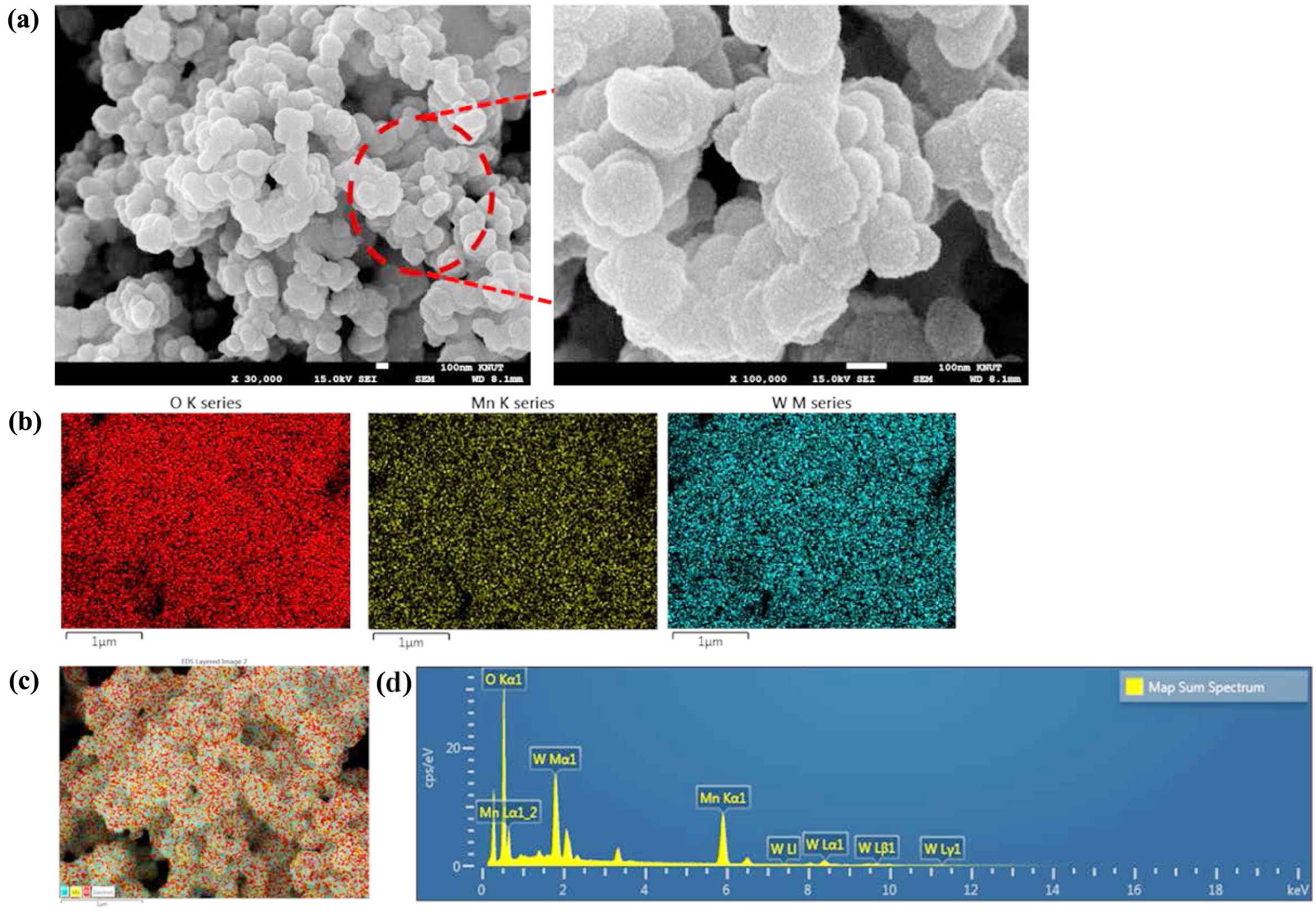

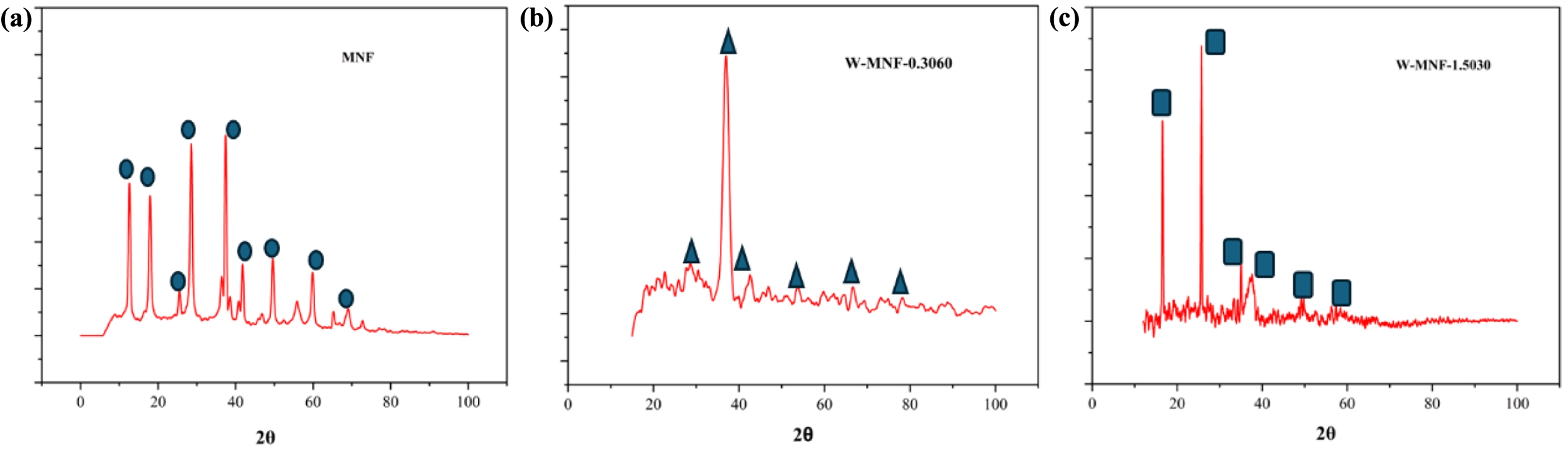

This Mn2+ oxidises the MnCl2 to form MnO2. Here the sulphuric acid plays a crucial role, such as stabilising the redox reaction and controlling the oxidation state of manganese by adjusting the redox potential of the medium. The nitrogen atmosphere maintains the controlled growth by prohibiting any unwanted oxidation. The doping of tungsten was also performed in similar fashion but performed in dark. When WCl6 came on contact with acidic pH, it gets dissociated to form W6+ ions which later combined into the MnO2 nanostructure. The FESEM structure of pristine MNF (Figure 1) and doped MNFs (Figure 2 and 3) showed clear changes which can be seen with the naked eye. The flower petal shape of pristine MNFs got reengineered when doping was introduced. This clearly affect the surface area and other properties. The more dopant amount introduced inside the framework, the morphology changes. This affects the surface area as well as other properties. Now from EDS spectrum data, it was revealed that 9.73 and 28.20 wt% of tungsten found in the W-MNF-0.3060 and W-MNF-1.5307. The primary weight analysis of those samples and dopant concentration are to be attributed to the structural characteristics. The morphology was also deeply analysed by means of XRD. The pristine MnO2 nanoflowers (MNF) exhibit 9 distinct diffraction peaks in the XRD pattern, all of which are consistent with the standard reference pattern for α-MnO₂ (PDF 00-44-0141). This indicates that the initial phase is highly crystalline α-MnO₂ with a tunnel-type structure. It is characterised by a 2×2 tunnel structure formed by edge- and corner-sharing MnO6 octahedra. Mn exists in +4 oxidation state, no metallic Mn (Mn0) is expected. Upon tungsten doping, notable structural changes are observed. For the W-MNF-0.3060 variant, a significant peak emerges at 37.342°, which does not appear in pristine MnO2. This peak match three distinct phases according to the following JCPDS cards, PDF 01-074-6605 – likely corresponding to a W-substituted Mn oxide or mixed-phase oxide, PDf 01-078-6777 – possibly indicating formation of a tungstate or W-incorporated Mn-O framework and PDF 01-082-0728 – suggesting the presence of a tungsten-rich phase or intermediate oxide. This suggests that at low doping concentration (0.3060), tungsten is partially incorporated into the MnO2 lattice, either by substituting Mn4+ or interstitially distorting the lattice. The presence of the α-MnO₂ phase is largely retained, indicating that the crystal framework remains predominantly manganese-based with only minor phase segregation. In contrast, the XRD pattern of W-MNF-0.3060 shows a drastic transformation. The emergence of three new dominant peaks at 16.537°, 25.733°, and 35.063°, which match with PDF 01-086-0134 and PDF 01-084-0886, points toward the formation of tungsten-rich phases, such as H2WO4 like structure or WO3 or its hydrates or complex W–O–Mn oxides with distorted octahedral units. These phases suggest a breakdown or replacement of the MnO2 lattice due to excessive W incorporation. This is supported by the absence of α-MnO2 characteristic peaks in the 1.5030 variant, indicating that at high doping, the MnO2 lattice can’t accommodate further W6+ ions, leading to the collapse or several distortion of the host structure whilst at low doping substitutional or interstitial doping of W6+ into the α-MnO₂ framework occurs, leading to minor new peaks alongside the α-MnO₂ phase (Figure 4).

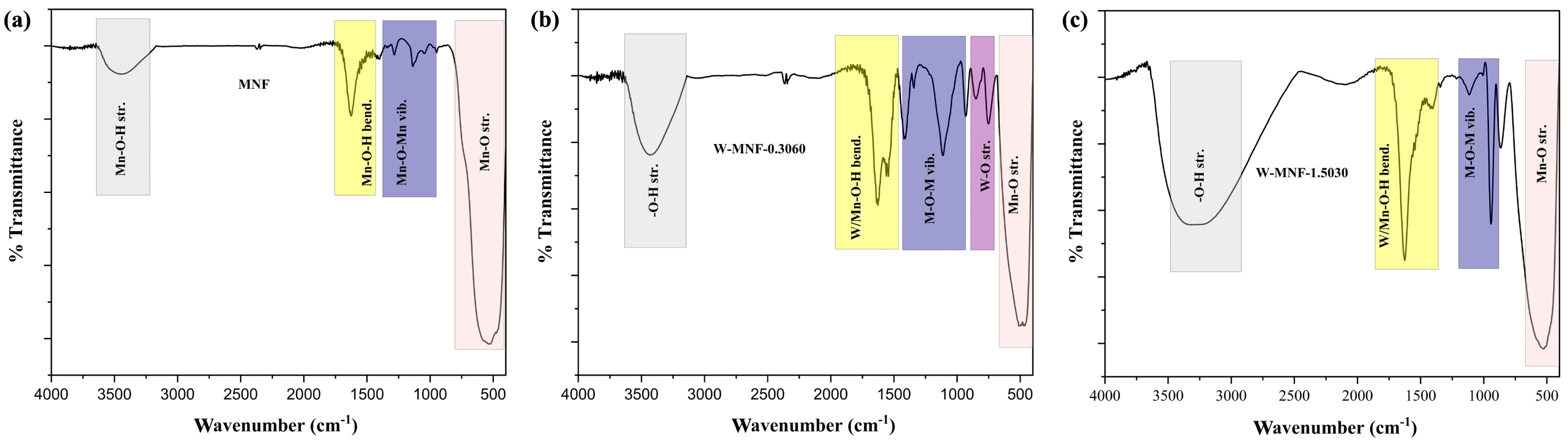

IR Analysis. IR spectroscopy reveals a deeper understanding of bonding inside the moiety which further our causes. To the pristine MNF, the grey area around 3400 cm-1, we observe a broad spectrum which is attributed to the surface hydroxyl group absorbed by the manganese centres.28

Similar thing we can see in the spectrum of W-MNF-0.3060. But the intensity is higher compared to the pristine one. This can be said that, as tungsten is substituting the manganese centres via doping procedure, this case the stretching of W-O-H and Mn-O-H is getting combined. Around 1630 cm-1 is also similar phenomenon is shown in both MNF and W-MNF-0.3060 but in the later case extra peak is observed around 1535 cm-1. These peaks are usually marked as metal and hydroxyl bond bending frequency. From 960 cm-1 to 1270 cm-1 is usually designated for Mn-O-Mn stretching and bending frequency region. But in the later case several peaks are observed due to multiple metal centres are present. Peaks around 1434 and 1312 cm-1 is marked as Mn-O-Mn stretching and bending whilst the peak around 1100 cm-1 is marked as W-O-Mn vibrations. The W-O stretching frequencies are pointed in W-MNF-0.3060 IR spectra at 847 and 743 cm-1 29

and in both cases the Mn-O stretching is observed around 500 cm-1, but due to the presence of tungsten in the moiety, the later one showed a little downshift (Figure 5). The FTIR spectrum of W-MNF-1.5030 exhibits similar characteristic shifts as observed in W-MNF-0.3060; however, a notable difference is the absence of the W–O stretching vibration in W-MNF-1.5030, which is distinctly present in W-MNF-0.3060. This absence may indicate a different mode of tungsten incorporation at higher doping levels, possibly due to lattice saturation or a shift from terminal W–O bonding to more delocalized W–O–Mn or W–O–W bridging environments. Such structural variations could lead to diminished IR activity for the W–O stretching mode, thereby explaining its disappearance in the higher-doped sample.

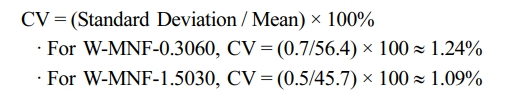

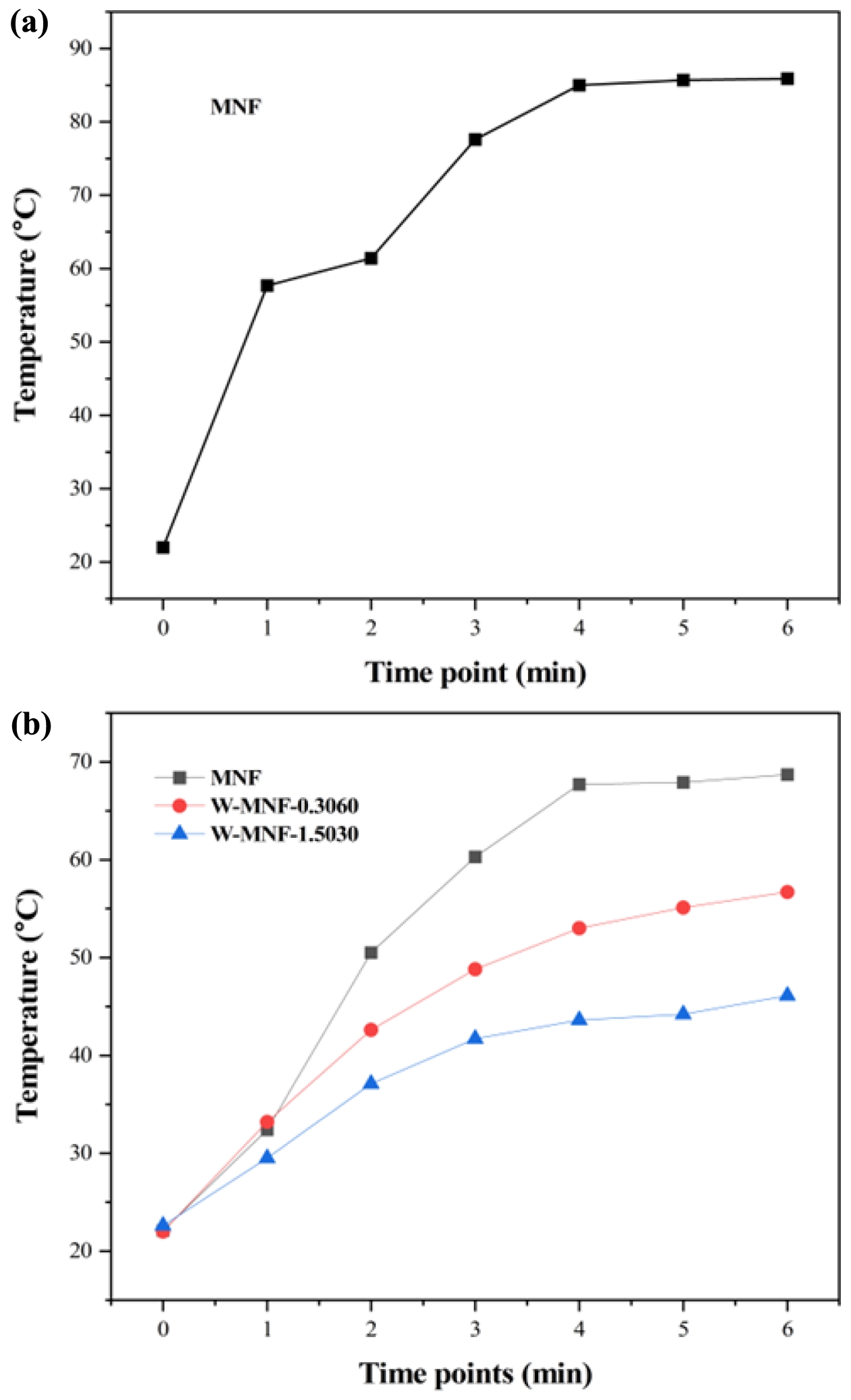

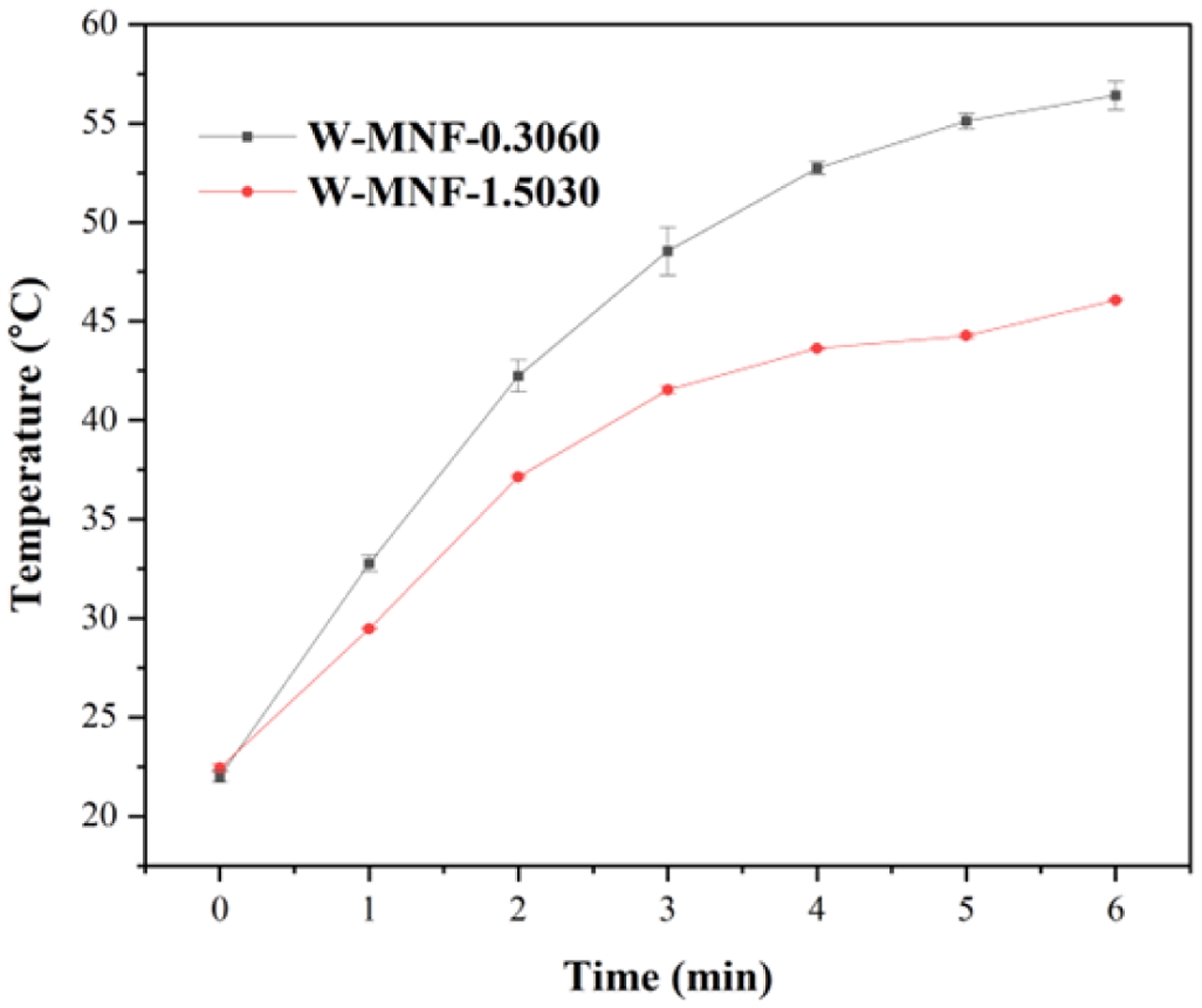

Photothermal Effect and Associated Phenomena. Converting the light energy to heat is the primary principle for this manganese networks. Here when they were irradiated with 808 nm laser for 6 minutes, different temperature maxims (Tmax) were achieved. For pristine MNF, the Tmax was 85.9 ℃ was achieved (Figure 6(a)) while the concentration maintained at 1 mg/mL and laser power 3 W/cm2. This high temperature can be assigned to the unhinged MnO2 centres in the moiety. This acted as a calibration of the whole project. Two constraints were considered as lowering the laser power to the physiological tolerance and usage of doped materials. When the concentration was reduced to 500 μL, laser power 2W/cm2, the achieved Tmax for MNF, W-MNF-0.3060 and W-MNF-1.5030 were 68.7, 56.7 and 46.1 ℃ respectively (Figure 6(b)) within 6 minutes. As we can see, the amount of doping clearly affected the moiety and as well as the conversion capability. From this, it was evident that at lower concentration, W-MNF-0.3060 is better compared to the higher doped hierarchy. This temperature can be useful while the need of aggressive treatment and if the tumour microenvironment is poor in terms of heat retention, then higher temperature will be fruitful. For these certain considerations, we have focused only W-MNF-0.3060 to build up a comparative study with pristine MNF. The reproducibility of the synthesis process was examined by evaluating the photothermal performance across several independently prepared batches. In our system, the peak photothermal temperature (Tmax) acts as a crucial gauge of the stability in doping levels and the uniformity of morphology. Any substantial variation in these factors would likely lead to remarkable changes in Tmax, as indicated by increased standard deviations. To validate the reproducibility, the samples W-MNF-0.3060 and W-MNF-1.5030 were synthesised in triplicate, and photothermal experiments were performed under identical conditions. The average Tmax for W-MNF-0.3060 was 56.4 ± 0.7 ℃, and for W-MNF-1.5030 it was 45.7 ± 0.5 ℃. These results were consistent with the primary experiments and indicate a high degree of reproducibility (Figure 7). To quantify this consistency, we calculated the coefficient of variation (CV), defined as:

Both values fall well below the commonly accepted 5% threshold, confirming excellent batch-to-batch consistency.

These low CV values, combined with the minimal standard deviations, strongly suggest that the synthesis process yields uniform doping and morphologically consistent nanostructures. Furthermore, we are confident that the consistent photothermal performance indicates an even distribution of doping and a uniform structure. In our system, tungsten doping directly affects the photothermal behaviour by modulating electronic absorption and lattice thermal conductivity. Consequently, any significant changes in doping levels or particle morphology would likely lead to corresponding variations in Tmax. The consistency observed across various synthesis batches instils a strong assurance in the reliability of the process.

In conclusion, we have meticulously assessed the consistency of our synthesis by conducting multiple fabrication and photothermal evaluations. The consistently low standard deviations in Tmax, coupled with a strong alignment with primary results, indicate that the synthetic approach produces morphologically and compositionally uniform W-MNF materials, showcasing remarkable batch-to-batch reproducibility.

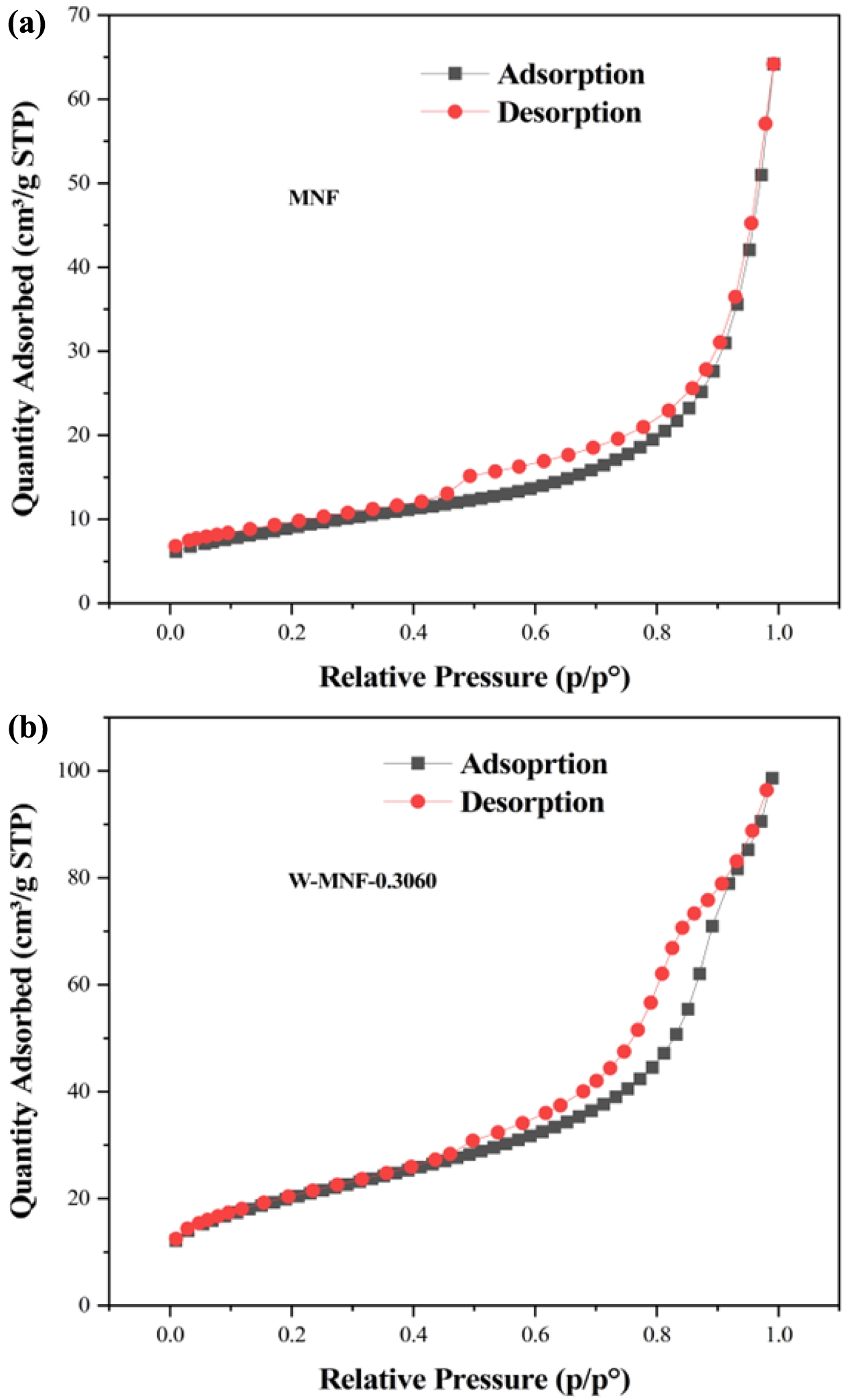

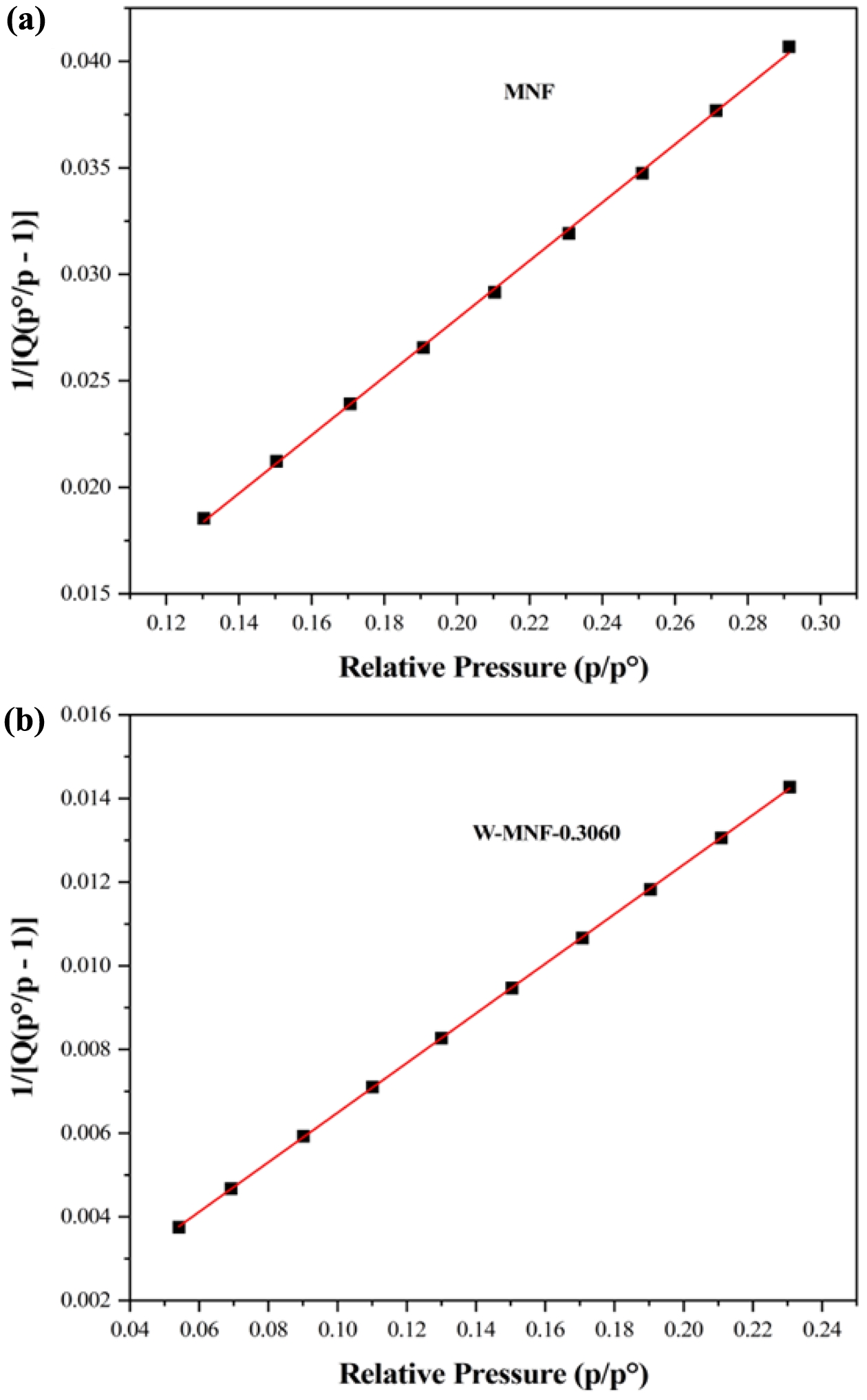

Surface Area Analysis with Doped MNF. N2 adsorption-desorption experiments were implemented to check the nanoflowers surface morphology as well as porosity category. According to the IUPAC guidelines30

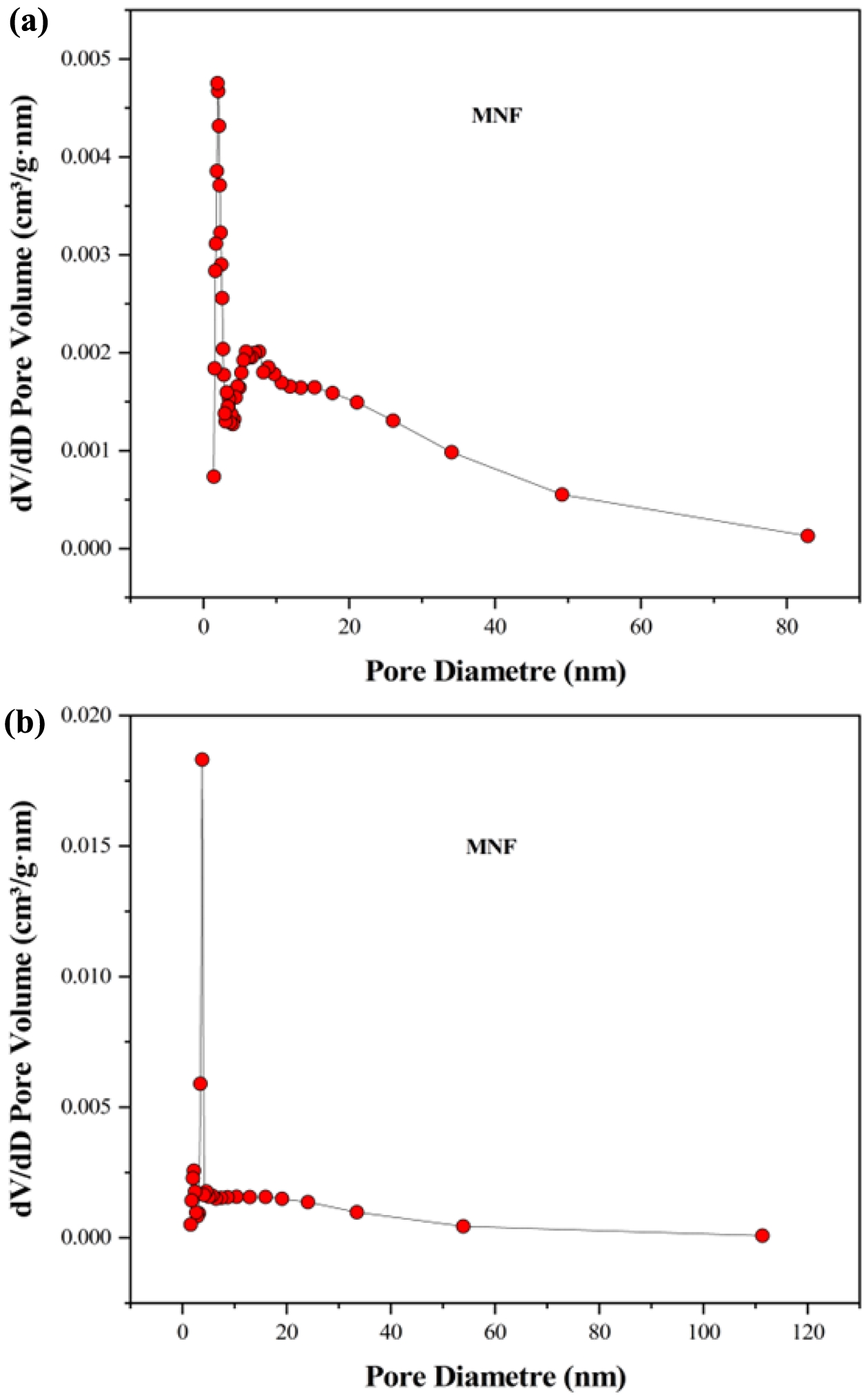

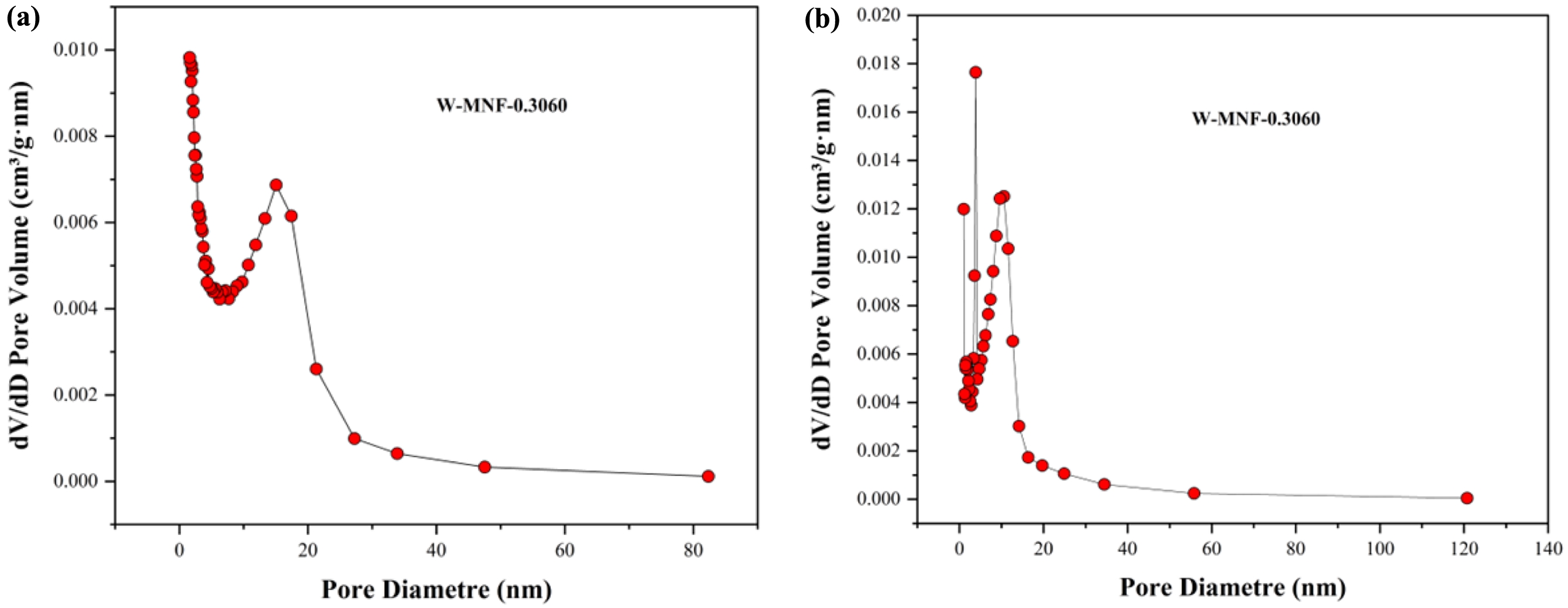

pristine MNF and W-MNF-0.3060 showed a type IV(a) isotherm consistent with a mesoporous material where the pore diameter lies in the range of 2-50 nm. The hysteresis loop is inconsistent in both structures. The MNF exhibits H3 type loops which implicate the simpler mesoporous structure whilst the W-MNF-0.3060 shows a H4 type of loops where it suggests that doping has altered the network connectivity significantly and by which introduced a mixture of narrow mesopores (Figure 8). The BET surface area plot revealed the surface area increase from pristine MNF to doped MNF. The BET surface area was calculated (Figure 9) from the 1/[Q(p0/p-1)] vs. relative pressure (p/p0) plot of MNF, which was found to be 32.4775 ± 0.0997 m2/g whilst the for W-MNF-0.3060 showed 72.6977 ± 0.1423 m2/g (in both cases the R2 value was found to be 0.99954 and 0.99997). This significant increase of surface area can partially explain the PTT ability of these two materials. As for doped structure, the active surface area increased significantly which in terms can dissipate the light energy significantly, that in turns lower the generated heat amount. Finally, the pore structure was assessed by adsorption-desorption dV/dD pore volume plot against pore diametre for both MNF and W-MNF-0.3060 (Figure 10, 11). For adsorption-desorption case, pristine MNF showed single sharp peak at mesoporous region whilst the later one showed a broad peak at mesoporous region for adsorption and for desorption mixed peaks were exhibited ranging micropore-mesopore region. This later phenomenon can be described by an array of things such as pore blocking, capillary condensation.31

During desorption, the rapid release of adsorbed gas sometimes enhances the sharp peaks. From the BET analysis, average pore diametre was measured along with the pore volume. The BJH adsorption pore volume was found to be increased from 0.096 to 0.14 cm3/g while comparing pristine and doped structure. Similarly, the doped structure demonstrated lower BJH adsorption pore diametre, 8.96 nm compared to the pristine MNF, 14.00 nm. This proves our initial hypothesis, creation of narrow mesopores after doping.

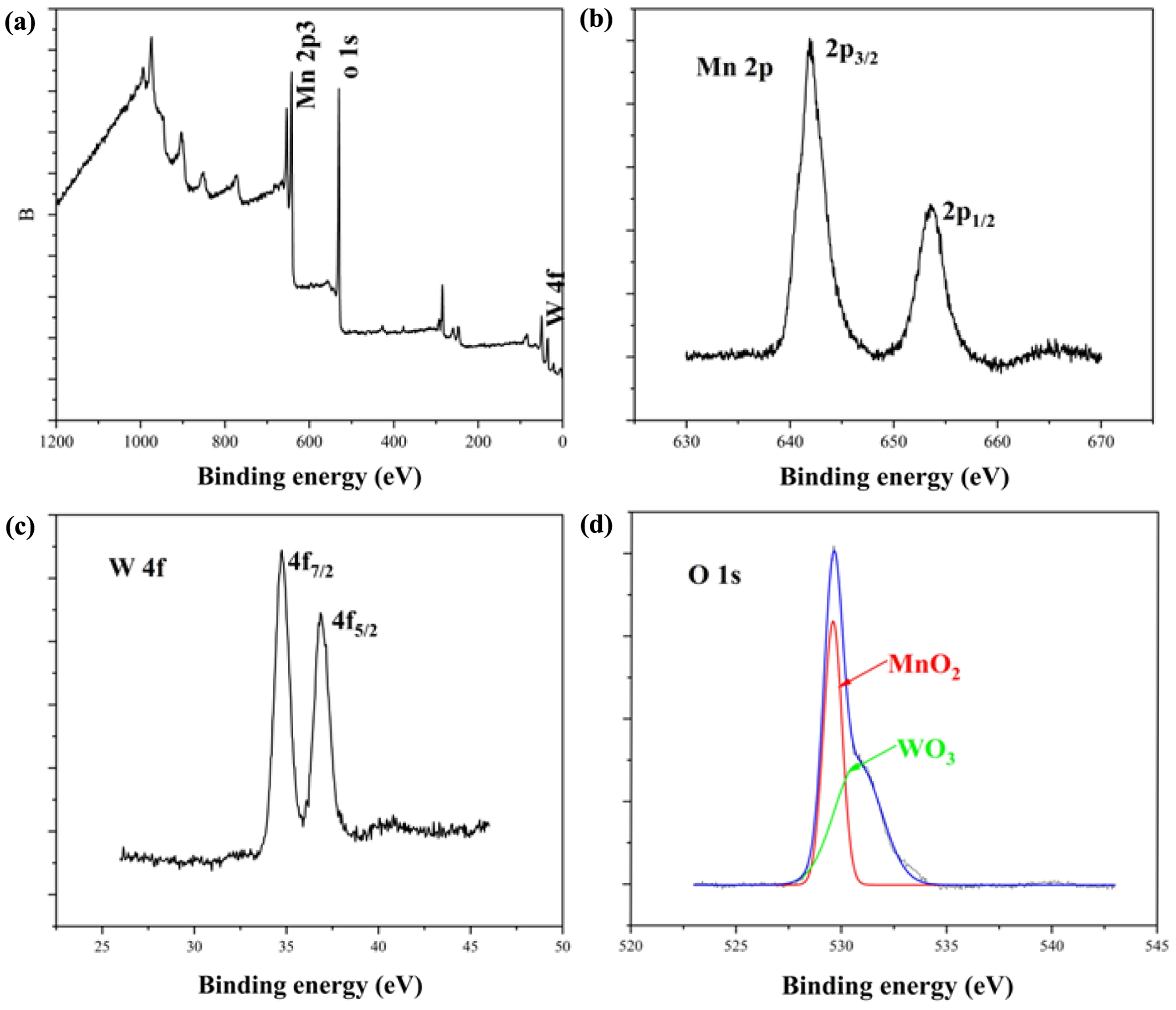

XPS Analysis. XPS analysis proved a pivotal role while assessing the inner chemistry of doped MNF (W-MNF-0.3060) (Figure 12). In the Mn 2p spectra we have seen the two peaks around 653.6 and 641.9 eV, which are credited to the Mn 2p1/2 and 2p3/2 transitions respectively. These are coming from the Mn(IV) state present in the MnO2 morphology.32

The tungsten showed two peaks around 34.7 and 36.8 eV which is a standalone reference for WO3 materials and credited to 4f7/2 and 4f5/2 transitions. This position indeed confirms the presence of more stable W6+ oxidation state which was achieved by the initial stages of dissociation in presence of acidic pH. The O1s peaks needed to be deconvoluted due to the presence of a shoulder. Which can be said that the main peak is corresponds to the oxygen moiety in MnO2,33 and the shoulder is from the WO3.34

Two different sources of oxygen are being accounted for. These peaks are at 529.5 and 530.7 eV. The survey spectrum is showed for the main peaks where the auger transitions and inner orbital transitions are not accounted for. For other deep insight into the chemical interferences of metal ions, a study with UPS is recommended.

Cytotoxicity Evaluation. The 4T1 cell line is derived from mouse breast cancer and closely mimics human triple-negative breast cancer, or TNBC, characterised by the absence of ER, PR, and HER2. The cancer presents significant challenges due to its aggressive nature and limited treatment alternatives, positioning it as a prime candidate for innovative therapies such as PTT, which have the potential to address drug resistance effectively. 4T1 cells exhibit a remarkably high ability to metastasise, naturally disseminating to the lungs, liver, brain, and bone following orthotopic implantation. This feature enables the evaluation of primary tumour ablation through PTT, as well as the potential impacts on metastatic progression—an aspect that traditional cell lines such as MCF7 are unable to provide. Another reason for utilising 4T1 cells is their natural resistance to various chemotherapeutics, rendering them appropriate for evaluating PTT as a non-drug-based alternative for challenging tumours. The 4T1 model has become a prominent tool in photothermal therapy research, facilitating comparative benchmarking and standardised progression across various studies. The utilisation of 4T1 breast cancer cells provides a pertinent and aggressive model for examining the efficacy of our tungsten-doped manganese nanomaterials in conjunction with heat treatment. This approach enables a comprehensive assessment of tumour recurrence and the immune response, positioning it as a robust candidate for in-depth investigation in photothermal therapy. As we mentioned before, this is the idea of introducing W doping into manganese nanoflower which is widely used in energy devices but a very less examples in cancer therapies. Our next works will be focusing on the 4T1 breast cancer models and in-depth biological studies. Understanding the toxicological profiles of therapeutic systems is crucial for the translational application of basic research from the lab to the clinic. Therefore, we evaluated the cytotoxicity of both pristine and doped MNFs. After 48 h of incubation, all those materials showed insignificant cytotoxic profiles, with a minimum of 80% cell survival rate in all the concentration (Figure 13). These findings confirmed an excellent biocompatible profile of pristine MNF and doped MNFs. The inference suggests that it could be applied to in vivo research. The experiment was repeated thrice (n=5), and data were expressed as standard deviation. The whole idea of this manuscript was the initiation of an idea where introduction of a nanostructure with doping was introduced to make it a plausible candidate for photothermal therapy. Now while considering the W-MNF-1.5307, the Tmax reached 46.1 ℃ which is almost 10 ℃ lesser than the W-MNF-0.3060. Now, at this temperature, aggressive hyperthermia is not possible at the dedicated tumour sites. This was the turning point where we took the decision as going through the cytotoxicity assessment only with the W-MNF-0.3060. In future works, we have planned for detailed studies with this only.

|

Figure 1 FESEM image of pristine MNF at different magnification level. |

|

Figure 2 (a) FESEM of W-MNF-0.3060 at different magnification level; (b) EDS mapping of different atoms; (c) merged image; (d) EDS analysis. |

|

Figure 3 (a) FESEM of W-MNF-1.5307 at different magnification level; (b) EDS mapping of different atoms; (c) merged image; (d) EDS analysis. |

|

Figure 4 XRD peaks of (a) MNF; (b) W-MNF-0.3060; (c) W-MNF-1.5030. All the major peaks are noted with respective shapes which are included in the graphs. MNF was matched with PDF 00-44-0141, W-MNF-0.3060 was matched with PDF 01-074-6605, PDF 01-078-6777 and PDF 01-082-0728 and W-MNF-1.5030 was matched with PDF 01-086-0134 and PDF 01-084-0886. |

|

Figure 5 IR spectra of (a) MNF; (b) W-MNF-0.3060; (c) W-MNF-1.5030. |

|

Figure 6 Photothermal experiments to monitor Tmax: (a) pristine MNF with 1 mg/mL concentration and 3 W/cm2 laser power for determining the initial constraints; (b) MNF, W-MNF-0.3060, and W-MNF-1.5030 with 500 μg/mL concentration and 2.1 W/cm2 , laser power. |

|

Figure 7 Photothermal output to assess the batch to batch reproducibility. Synthesis were performed thrice and output was calculated by means of average and standard deviation. Initial temperature was found to be different as both the experiments were performed in different dates. |

|

Figure 8 Isotherm linear plot: (a) MNF; (b) W-MNF-0.3060. |

|

Figure 9 BET surface area plot |

|

Figure 10 (a) adsorption; (b) desorption dV/dD pore volume vs. pore diametre plot for MNF. |

|

Figure 11 (a) adsorption; (b) desorption dV/dD pore volume vs pore diametre plot for W-MNF-0.3060. |

|

Figure 12 XPS spectrum of W-MNF-0.3060; (a) survey; (b) Mn2p; (c) W4f; (d) O1s. |

|

Figure 13 Cytotoxicity profiles of (a) pristine MNF; (b) W-MNF0.3060 at different concentrations and data expressed in ± standard deviation. The experiment was repeated thrice (n=5). |

In summary, we have successfully tuned the inner morphology of primary MNF structure with a controlled amount of doping which put the hyperthermia at a favourable region where irreversible tissue damage can be avoided. The synthesised W-MNF-0.3060 is utilised properly with a structural idea. In future, this effective synthetic method can be exploited to refashion further the structural integrity of manganese nanoflower with various metal doping to use in photothermal therapy.

- 1. Plaza, J. L.; Carcelén, V. Conductive Properties of Foam and Cluster Structures Created from Hexanthiol-Passivated Gold Nanoparticles. Appl. Surf. Sci. 2009, 255, 6164-6167.

-

- 2. Lassoued, A.; Lassoued, M. S.; Dkhil, B.; Ammar, S.; Gadri, A. Synthesis, Photoluminescence and Magnetic Properties of Iron Oxide (α-Fe2O3) Nanoparticles through Precipitation or Hydrothermal Methods. Phys. E Low-dimensional Syst. Nanostructures 2018, 101, 212-219.

-

- 3. Paradise, M.; Goswami, T. Carbon Nanotubes – Production and Industrial Applications. Mater. Des. 2007, 28, 1477-1489.

-

- 4. Vargason, A. M.; Anselmo, A. C.; Mitragotri, S. The Evolution of Commercial Drug Delivery Technologies. Nat. Biomed. Eng. 2021, 5, 951-967.

-

- 5. Ghazal, H.; Waqar, A.; Yaseen, F.; Shahid, M.; Sultana, M.; Tariq, M.; Bashir, M. K.; Tahseen, H.; Raza, T.; Ahmad, F. Role of Nanoparticles in Enhancing Chemotherapy Efficacy for Cancer Treatment. Next Mater. 2024, 2, 100128.

-

- 6. Amos, J. D.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, Z.; Lowry, G. V.; Wiesner, M. R.; Hendren, C. O. The NanoInformatics Knowledge Commons: Capturing Spatial and Temporal Nanomaterial Transformations in Diverse Systems. NanoImpact 2021, 23, 100331.

-

- 7. Park, J.; Ham, S.; Jang, M.; Lee, J.; Kim, S.; Kim, S.; Lee, K.; Park, D.; Kwon, J.; Kim, H.; Kim, P.; Choi, K.; Yoon, C. Spatial–Temporal Dispersion of Aerosolized Nanoparticles During the Use of Consumer Spray Products and Estimates of Inhalation Exposure. Environ. Sci. Technol. 2017, 51, 7624-7638.

-

- 8. Li, J.; Zhang, W.; Ji, W.; Wang, J.; Wang, N.; Wu, W.; Wu, Q.; Hou, X.; Hu, W.; Li, L. Near Infrared Photothermal Conversion Materials: Mechanism, Preparation, and Photothermal Cancer Therapy Applications. J. Mater. Chem. B 2021, 9, 7909-7926.

-

- 9. Xu, Y.; Zou, M.; Wang, H.; Zhang, L.; Xing, M.; He, M.; Jiang, H.; Zhang, Q.; Kauppinen, E. I.; Xin, F.; Tian, Y. Upconversion Nanoparticles@single-Walled Carbon Nanotubes Composites as Efficient Self-Monitored Photo-Thermal Agents. Spectrochim. Acta Part A Mol. Biomol. Spectrosc. 2023, 303, 123173.

-

- 10. Izakura, S.; Gu, W.; Nishikubo, R.; Saeki, A. Photon Upconversion through a Cascade Process of Two-Photon Absorption in CsPbBr3 and Triplet–Triplet Annihilation in Porphyrin/Diphenylanthracene. J. Phys. Chem. C 2018, 122, 14425-14433.

-

- 11. Doaga, A.; Cojocariu, A. M.; Amin, W.; Heib, F.; Bender, P.; Hempelmann, R.; Caltun, O. F. Synthesis and Characterizations of Manganese Ferrites for Hyperthermia Applications. Mater. Chem. Phys. 2013, 143, 305-310.

-

- 12. Wang, J.; Wu, X.; Shen, P.; Wang, J.; Shen, Y.; Shen, Y.; Webster, T. J.; Deng, J. Applications of Inorganic Nanomaterials in Photothermal Therapy Based on Combinational Cancer Treatment. Int. J. Nanomedicine 2020, 15, 1903-1914.

-

- 13. Leto, D. F.; Jackson, T. A. Mn K-Edge X-Ray Absorption Studies of Oxo- and Hydroxo-Manganese(IV) Complexes: Experimental and Theoretical Insights into Pre-Edge Properties. Inorg. Chem. 2014, 53, 6179-6194.

-

- 14. Pleau, E.; Kokoszka, G. Electron Paramagnetic Resonance Studies of Metal–Metal Interactions in Manganese(II) Complexes. The 10/3 Effect. J. Chem. Soc., Faraday Trans. 2 1973, 69, 355-362.

-

- 15. Sinopoli, A.; La Porte, N. T.; Martinez, J. F.; Wasielewski, M. R.; Sohail, M. Manganese Carbonyl Complexes for CO2 Reduction. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2018, 365, 60-74.

-

- 16. Bai, S.-P.; Lu, L.; Wang, R.-L.; Xi, L.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Luo, X.-G. Manganese Source Affects Manganese Transport and Gene Expression of Divalent Metal Transporter 1 in the Small Intestine of Broilers. Br. J. Nutr. 2012, 108, 267-276.

-

- 17. Ashrafizadeh, M.; Ahmadi, Z.; Samarghandian, S.; Mohammadinejad, R.; Yaribeygi, H.; Sathyapalan, T.; Sahebkar, A. MicroRNA-Mediated Regulation of Nrf2 Signaling Pathway: Implications in Disease Therapy and Protection against Oxidative Stress. Life Sci. 2020, 244, 117329.

-

- 18. Duan, J.; Liao, T.; Xu, X.; Liu, Y.; Kuang, Y.; Li, C. Metal-Polyphenol Nanodots Loaded Hollow MnO2 Nanoparticles with a “Dynamic Protection” Property for Enhanced Cancer Chemodynamic Therapy. J. Colloid Interface Sci. 2023, 634, 836-851.

-

- 19. Jung, K.-W.; Lee, S. Y.; Lee, Y. J.; Choi, J.-W. Ultrasound-Assisted Heterogeneous Fenton-like Process for Bisphenol A Removal at Neutral PH Using Hierarchically Structured Manganese Dioxide/Biochar Nanocomposites as Catalysts. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 57, 22-28.

-

- 20. Xiao, M.; Qi, Y.; Feng, Q.; Li, K.; Fan, K.; Huang, T.; Qu, P.; Gai, H.; Song, H. P-Cresol Degradation through Fe(III)-EDDS/H2O2 Fenton-like Reaction Enhanced by Manganese Ion: Effect of PH and Reaction Mechanism. Chemosphere 2021, 269, 129436.

-

- 21. de Oliveira Ribeiro, R. A.; Zuta, U. O.; Soares, I. P. M.; Anselmi, C.; Soares, D. G.; Briso, A. L. F.; Hebling, J.; de Souza Costa, C. A. Manganese Oxide Increases Bleaching Efficacy and Reduces the Cytotoxicity of a 10% Hydrogen Peroxide Bleaching Gel. Clin. Oral Investig. 2022, 26, 7277-7286.

-

- 22. Li, Y.; Tian, X.; Lu, Z.; Yang, C.; Yang, G.; Zhou, X.; Yao, H.; Zhu, Z.; Xi, Z.; Yang, X. Mechanism for α-MnO2 Nanowire-Induced Cytotoxicity in Hela Cells. J. Nanosci. Nanotechnol. 2010, 10, 397-404.

-

- 23. Wang, F.; Zheng, Y.; Chen, Q.; Yan, Z.; Lan, D.; Lester, E.; Wu, T. A Critical Review of Facets and Defects in Different MnO2 Crystalline Phases and Controlled Synthesis – Its Properties and Applications in the Energy Field. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2024, 500, 215537.

-

- 24. Sharma, S.; Batra, S.; Chauhan, M. K.; Kumar, V. Photothermal Therapy for Cancer Treatment. In Targeted Cancer Therapy in Biomedical Engineering; Springer: Singapore, 2023; pp 755-780.

-

- 25. Zhang, D.; Dai, J.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, H.; Xu, Y.; Wu, J.; Li, P. Preparation of Spherical Δ−MnO2 Nanoflowers by One-Step Coprecipitation Method as Electrode Material for Supercapacitor. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 18032-18045.

-

- 26. Chu, K.; Liu, Y.; Li, Y.; Guo, Y.; Tian, Y.; Zhang, H. Multi-Functional Mo-Doping in MnO2 Nanoflowers toward Efficient and Robust Electrocatalytic Nitrogen Fixation. Appl. Catal. B Environ. 2020, 264, 118525.

-

- 27. Cheney, M. A.; Bhowmik, P. K.; Moriuchi, S.; Birkner, N. R.; Hodge, V. F.; Elkouz, S. E. Synthesis and Characterization of Two Phases of Manganese Oxide from Decomposition of Permanganate in Concentrated Sulfuric Acid at Ambient Temperature. Colloids Surfaces A Physicochem. Eng. Asp. 2007, 307, 62-70.

-

- 28. Mondal, J.; Srivastava, S. K. δ-MnO2 Nanoflowers and Their Reduced Graphene Oxide Nanocomposites for Electromagnetic Interference Shielding. ACS Appl. Nano Mater. 2020, 3, 11048-11059.

-

- 29. Islam, M. S.; Hoque, S. M.; Rahaman, M.; Islam, M. R.; Irfan, A.; Sharif, A. Superior Cyclic Stability and Capacitive Performance of Cation- and Water Molecule-Preintercalated δ-MnO2/h-WO3 Nanostructures as Supercapacitor Electrodes. ACS Omega 2024, 9, 10680-10693.

-

- 30. Thommes, M.; Kaneko, K.; Neimark, A. V.; Olivier, J. P.; Rodriguez-Reinoso, F.; Rouquerol, J.; Sing, K. S. W. Physisorption of Gases, with Special Reference to the Evaluation of Surface Area and Pore Size Distribution (IUPAC Technical Report). Pure Appl. Chem. 2015, 87, 1051-1069.

-

- 31. Gor, G. Y.; Huber, P.; Bernstein, N. Adsorption-Induced Deformation of Nanoporous Materials—A Review. Appl. Phys. Rev. 2017, 4.

-

- 32. Allen, G. C.; Harris, S. J.; Jutson, J. A.; Dyke, J. M. A Study of a Number of Mixed Transition Metal Oxide Spinels Using X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. Appl. Surf. Sci. 1989, 37, 111-134.

-

- 33. Tan, B. J.; Klabunde, K. J.; Sherwood, P. M. A. XPS Studies of Solvated Metal Atom Dispersed (SMAD) Catalysts. Evidence for Layered Cobalt-Manganese Particles on Alumina and Silica. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 1991, 113, 855-861.

-

- 34. Nefedov, V. I.; Salyn, Y. V.; Leonhardt, G.; Scheibe, R. A Comparison of Different Spectrometers and Charge Corrections Used in X-Ray Photoelectron Spectroscopy. J. Electron Spectros. Relat. Phenomena 1977, 10, 121-124

-

- Polymer(Korea) 폴리머

- Frequency : Bimonthly(odd)

ISSN 2234-8077(Online)

Abbr. Polym. Korea - 2024 Impact Factor : 0.6

- Indexed in SCIE

This Article

This Article

-

2026; 50(1): 1-13

Published online Jan 25, 2026

- 10.7317/pk.2026.50.1.1

- Received on Jan 30, 2025

- Revised on Jul 17, 2025

- Accepted on Jul 17, 2025

Services

Services

- Full Text PDF

- Abstract

- ToC

- Acknowledgements

- Conflict of Interest

Introduction

Experimental

Results and Discussion

Conclusion

- References

Shared

Correspondence to

Correspondence to

- Yong-kyu Lee

-

Department of Chemical & Biological Engineering, Korea National University of Transportation, Chungju 27470, Korea

- E-mail: leeyk@ut.ac.kr

- ORCID:

0000-0001-8336-3592

vs. relative pressure) for (a) MNF; (b) W-MNF-0.3060.

vs. relative pressure) for (a) MNF; (b) W-MNF-0.3060.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.

Copyright(c) The Polymer Society of Korea. All right reserved.